Next: Bibliography Up: Toroidal Tearing Modes Previous: Effect of Electromagnetic Torques Contents

Consider a magnetic island chain of width  that reconnects magnetic flux at the

that reconnects magnetic flux at the

th rational surface in the plasma. The toroidal equivalent of the cylindrical island width evolution equation, (12.15), is

th rational surface in the plasma. The toroidal equivalent of the cylindrical island width evolution equation, (12.15), is

,

,

,

,

is specified in Equation (14.125),

is specified in Equation (14.125),

, where

, where

is defined in Equation (A.98), and

Here,

is defined in Equation (A.98), and

Here,

denotes the non-inductive “bootstrap” component (i.e., the component that is driven by pressure gradients, rather than the

parallel electric field) of the equilibrium plasma current (see Section 2.20),

denotes the non-inductive “bootstrap” component (i.e., the component that is driven by pressure gradients, rather than the

parallel electric field) of the equilibrium plasma current (see Section 2.20),

is a flux-surface average operator [see Equation (A.82)],

and

is a flux-surface average operator [see Equation (A.82)],

and

. In writing Equation (14.196), we have neglected the relatively unimportant (for neoclassical tearing modes) island saturation term in the Rutherford equation. (See Section 12.2.)

We have also neglected the ion polarization term (because we have previously shown that this term is negligible). (See Section 12.4.) Finally, in accordance with the previous analysis in this chapter, we have assumed that

there is perfect shielding at all of the other rational surfaces in the plasma (i.e.,

. In writing Equation (14.196), we have neglected the relatively unimportant (for neoclassical tearing modes) island saturation term in the Rutherford equation. (See Section 12.2.)

We have also neglected the ion polarization term (because we have previously shown that this term is negligible). (See Section 12.4.) Finally, in accordance with the previous analysis in this chapter, we have assumed that

there is perfect shielding at all of the other rational surfaces in the plasma (i.e.,

for

for  ).

).

Equation (14.196) states that the width of the magnetic island chain evolves on the local (to the  th rational surface) resistive timescale,

th rational surface) resistive timescale,

, in response to the effective tearing stability index,

, in response to the effective tearing stability index,  [20], the destabilizing (because

[20], the destabilizing (because  is usually positive)

effect of the loss of the bootstrap current inside the chain's magnetic separatrix [3], and the stabilizing (because

is usually positive)

effect of the loss of the bootstrap current inside the chain's magnetic separatrix [3], and the stabilizing (because  is usually

negative) effect of magnetic field-line curvature [28].

is usually

negative) effect of magnetic field-line curvature [28].

Making use of Equation (A.99), it can be seen that the curvature term (i.e., the third term on the right-hand side) in Equation (14.196) is entirely consistent with the corresponding term in

Equation (12.15). However, our new curvature term is more general than our previous cylindrical version because the

calculation of the dimensionless curvature parameter  outlined in Section A.8 makes no assumptions about the

geometry of the equilibrium magnetic flux-surfaces (other than that they are axisymmetric) [21].

outlined in Section A.8 makes no assumptions about the

geometry of the equilibrium magnetic flux-surfaces (other than that they are axisymmetric) [21].

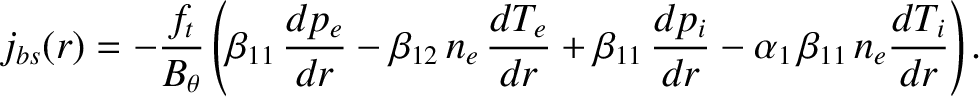

Making use of Equation (14.197), the bootstrap term (i.e., the second term on the right-hand side) in Equation (14.196) is equivalent to the corresponding term in Equation (12.15) provided that the parallel bootstrap current takes the form [see Equation (2.265)]

|

(14.198) |

is the fraction of trapped particles [see Equation (2.202)],

is the fraction of trapped particles [see Equation (2.202)],

the equilibrium poloidal magnetic field,

the equilibrium poloidal magnetic field,

the species-

the species- equilibrium pressure profile,

equilibrium pressure profile,

[see Equation (2.217)],

[see Equation (2.217)],

[see Equation (2.243)], and

[see Equation (2.243)], and

[see Equation (2.244)]. The previous expression is only valid when the fraction

of trapped particles is small, the magnetic flux-surfaces have circular cross-sections, there are no impurity ions, and the plasma lies in the

banana collisionality regime. However, we can formulate a more general expression for the bootstrap current using the analysis

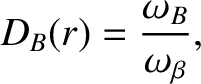

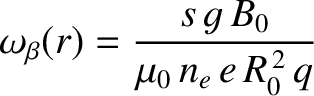

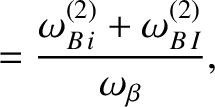

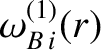

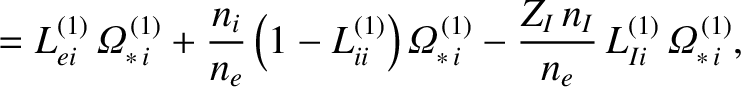

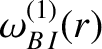

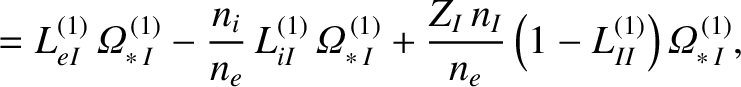

of Section A.7. If we define

which has the dimensions of a frequency, then we find that

[see Equation (2.244)]. The previous expression is only valid when the fraction

of trapped particles is small, the magnetic flux-surfaces have circular cross-sections, there are no impurity ions, and the plasma lies in the

banana collisionality regime. However, we can formulate a more general expression for the bootstrap current using the analysis

of Section A.7. If we define

which has the dimensions of a frequency, then we find that

|

|

|

|

||

|

(14.200) |

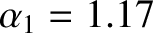

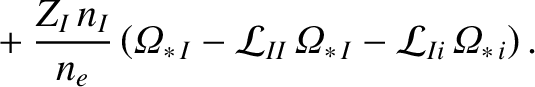

is the impurity ion charge number, the species-

is the impurity ion charge number, the species- number densities,

number densities,  , are defined in Equations (A.4) and (A.5), the diamagnetic frequencies,

, are defined in Equations (A.4) and (A.5), the diamagnetic frequencies,

, are specified in Equation (A.78), and the dimensionless neoclassical

parameters,

, are specified in Equation (A.78), and the dimensionless neoclassical

parameters,

, are defined in Equation (A.80). Moreover, use has been made of the quasi-neutrality constraint (A.1).

The previous expression makes no assumption about the geometry of the equilibrium magnetic flux-surfaces, does not assume that the fraction of

trapped particles is small or that the plasma is in the banana collisionality regime, and allows for the presence of impurity ions.

, are defined in Equation (A.80). Moreover, use has been made of the quasi-neutrality constraint (A.1).

The previous expression makes no assumption about the geometry of the equilibrium magnetic flux-surfaces, does not assume that the fraction of

trapped particles is small or that the plasma is in the banana collisionality regime, and allows for the presence of impurity ions.

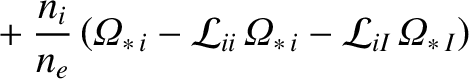

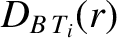

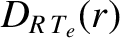

Equations (14.197) and (14.199) yield

|

(14.201) |

|

(14.202) |

.

.

As was mentioned in Section 12.4, the bootstrap and curvature terms in the generalized Rutherford equation, (14.196), depend crucially on an assumed flattening of the plasma pressure profile inside the magnetic separatrix of the island chain. However, if the island width falls below a certain threshold value then the transport of heat and particles along magnetic field-lines cannot compete with the anomalous transport of heat and particles across magnetic flux-surfaces, and the pressure flattening within the magnetic separatrix is lost [9]. Under these circumstances, we would expect a modification of the bootstrap and curvature terms in the generalized Rutherford equation [9,30].

According to the analysis of Reference [9], the critical value of  below which the electron temperature

fails to flatten inside the magnetic separatrix of our magnetic island chain can be written

below which the electron temperature

fails to flatten inside the magnetic separatrix of our magnetic island chain can be written

, and

Here,

, and

Here,  is the electron-ion collision time [see Equation (2.20)],

is the electron-ion collision time [see Equation (2.20)],

the electron thermal speed [see Equation (2.17)],

the electron thermal speed [see Equation (2.17)],

the (anomalous) electron perpendicular energy diffusivity, and

the (anomalous) electron perpendicular energy diffusivity, and

the electron parallel energy diffusivity.

Equation (14.205) specifies the parallel diffusivity predicted by the short mean-free-path theory of Braginskii [2]. [See Equation (2.54).] Note that this expression has been corrected into order to take into account the presence of impurity ions in the plasma. Equation (14.206) specifies the

parallel diffusivity predicted by the long mean-free-path theory of Section 2.23 [24,25] on the assumption that

the electron parallel energy diffusivity.

Equation (14.205) specifies the parallel diffusivity predicted by the short mean-free-path theory of Braginskii [2]. [See Equation (2.54).] Note that this expression has been corrected into order to take into account the presence of impurity ions in the plasma. Equation (14.206) specifies the

parallel diffusivity predicted by the long mean-free-path theory of Section 2.23 [24,25] on the assumption that

|

(14.207) |

th rational surface, of

width

th rational surface, of

width

. Finally, Equation (14.204) ensures that the parallel electron energy diffusivity never exceeds the limiting value set

by long mean-free-path theory. Equations (14.203)–(14.206) can be solved for

. Finally, Equation (14.204) ensures that the parallel electron energy diffusivity never exceeds the limiting value set

by long mean-free-path theory. Equations (14.203)–(14.206) can be solved for

via iteration.

via iteration.

According to the analysis of Reference [9], the critical value of  below which the ion temperature

fails to flatten inside the magnetic separatrix of our magnetic island chain can be written

below which the ion temperature

fails to flatten inside the magnetic separatrix of our magnetic island chain can be written

![$\displaystyle \frac{W_{T_i\,k}}{r_k} = \sqrt{8}\,\left[\frac{\chi_{\perp\,i}(r_...

...l\,i}(r_k)}\right]^{1/4} \left[\frac{1}{\epsilon(r_k)\,s(r_k)\,n}\right]^{1/2},$](img4584.png) |

(14.208) |

is the ion-ion collision time [see Equation (2.21)],

is the ion-ion collision time [see Equation (2.21)],

the ion thermal speed [see Equation (2.17)],

the ion thermal speed [see Equation (2.17)],

the (anomalous) ion perpendicular energy diffusivity, and

the (anomalous) ion perpendicular energy diffusivity, and

the ion parallel energy diffusivity.

The previous four equations must be solved iteratively to determine

the ion parallel energy diffusivity.

The previous four equations must be solved iteratively to determine

.

.

Finally, according to the analysis of Reference [9], the critical value of  below which the electron number density

fails to flatten inside the magnetic separatrix of our magnetic island chain can be written

below which the electron number density

fails to flatten inside the magnetic separatrix of our magnetic island chain can be written

![$\displaystyle \frac{W_{n_e\,k}}{r_k} = \sqrt{8}\,\left[\frac{D_{\perp}(r_k)}{\c...

...l\,i}(r_k)}\right]^{1/4} \left[\frac{1}{\epsilon(r_k)\,s(r_k)\,n}\right]^{1/2},$](img4596.png) |

(14.212) |

is the (anomalous) perpendicular particle diffusivity, and we have taken into account the fact that parallel particle

transport is constrained by the need to maintain amipolarity (which implies that the parallel particle diffusivity cannot exceed the

parallel ion diffusivity).

is the (anomalous) perpendicular particle diffusivity, and we have taken into account the fact that parallel particle

transport is constrained by the need to maintain amipolarity (which implies that the parallel particle diffusivity cannot exceed the

parallel ion diffusivity).

Table 14.9 specifies the critical  island widths below which the local electron temperature, the ion temperature, and the electron number density profiles fail to

flatten in our example tokamak discharge. These critical widths are calculated from the equilibrium and profile data

shown in Figures 14.1–14.3. It can be seen that the critical island width below

which the electron temperature profile fails to flatten,

island widths below which the local electron temperature, the ion temperature, and the electron number density profiles fail to

flatten in our example tokamak discharge. These critical widths are calculated from the equilibrium and profile data

shown in Figures 14.1–14.3. It can be seen that the critical island width below

which the electron temperature profile fails to flatten,

, is of order 2% of the plasma minor radius. On the other hand, the critical island width

below which the ion temperature profile fails to flatten,

, is of order 2% of the plasma minor radius. On the other hand, the critical island width

below which the ion temperature profile fails to flatten,

, is significantly larger than

, is significantly larger than

(because ions stream along magnetic field-lines

at a considerably slower rate than electrons) [9]. Finally, the critical island width below which the electron number density fails to

flatten,

(because ions stream along magnetic field-lines

at a considerably slower rate than electrons) [9]. Finally, the critical island width below which the electron number density fails to

flatten,

, lies between

, lies between

and

and

.

.

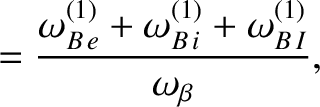

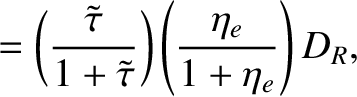

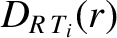

Let us generalize the right-hand side of the generalized Rutherford equation, (14.196), to take into account the incomplete flattening of the electron temperature, ion temperature, and electron number density profiles within the magnetic separatrix of the island chain. In order to achieve this goal, we need to identify which components of the bootstrap and curvature terms are associated with the flattening of the electron temperature, ion temperature, and electron number density profiles, and then modify these components in the appropriate manner. We shall assume that the majority ion and impurity ion temperature profiles both fail to flatten below the same critical island width. Likewise, we shall assume that the electron, majority ion, and impurity ion number density profiles all fail to flatten below the same critical island width. Taking these considerations into account, and making use of the analysis of References [9] and [30], we arrive at

where |

|

(14.217) |

|

|

(14.218) |

|

|

(14.219) |

|

|

(14.220) |

|

|

(14.221) |

|

|

(14.222) |

|

|

(14.223) |

|

|

(14.224) |

|

|

(14.225) |

|

|

(14.226) |

|

|

(14.227) |

|

|

(14.228) |

|

|

(14.229) |

|

|

(14.230) |

|

|

(14.231) |

|

![$\displaystyle = \left[\left(\frac{\tilde{\tau}}{1+\tilde{\tau}}\right)\left(\fr...

...eft(\frac{1}{1+\tilde{\tau}}\right)\left(\frac{1}{1+\eta_i} \right) \right]D_R,$](img4662.png) |

(14.232) |

|

|

(14.233) |

is defined in Equation (A.76), and the dimensionless neoclassical matrix elements

is defined in Equation (A.76), and the dimensionless neoclassical matrix elements

are specified in Section A.6. Of course,

are specified in Section A.6. Of course,

, et cetera.

, et cetera.

![\includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{Chapter14/Figure14_7.eps}](img4668.png)

|

Table 14.10 specifies the bootstrap and curvature parameters that appear on the right-hand sides of the generalized Rutherford equations,

(14.216), of the  tearing modes in our example tokamak discharge. These parameters are calculated from the equilibrium and profile data

shown in Figures 14.1–14.3, as well as the neoclassical theory set out in Appendix A.

It can be seen that the

tearing modes in our example tokamak discharge. These parameters are calculated from the equilibrium and profile data

shown in Figures 14.1–14.3, as well as the neoclassical theory set out in Appendix A.

It can be seen that the

,

,

, and

, and

parameters are all positive, indicating that the bootstrap terms in the Rutherford equations are destabilizing. On the other

hand, the

parameters are all positive, indicating that the bootstrap terms in the Rutherford equations are destabilizing. On the other

hand, the

,

,

, and

, and

parameters are all negative, indicating that the curvature terms in the Rutherford equations are stabilizing. It it also clear that the magnitudes of the

parameters are all negative, indicating that the curvature terms in the Rutherford equations are stabilizing. It it also clear that the magnitudes of the

,

,

, and

, and

parameters generally exceed those of the

parameters generally exceed those of the

,

,

, and

, and

parameters, which implies that the destabilizing effect of the perturbed bootstrap current is larger than the stabilizing effect

of magnetic field-line curvature.

parameters, which implies that the destabilizing effect of the perturbed bootstrap current is larger than the stabilizing effect

of magnetic field-line curvature.

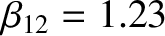

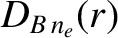

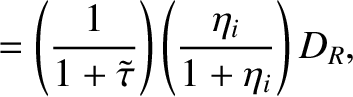

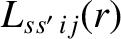

Finally, the right-hand sides of the generalized Rutherford equations of the  tearing modes in our example tokamak

discharge are plotted as functions of the normalized island widths in Figure 14.7. These right-hand sides are calculated from Equation (14.216)

using the data set out in Tables 14.2, 14.9, and 14.10.

It can be seen that only the

tearing modes in our example tokamak

discharge are plotted as functions of the normalized island widths in Figure 14.7. These right-hand sides are calculated from Equation (14.216)

using the data set out in Tables 14.2, 14.9, and 14.10.

It can be seen that only the  (i.e.,

(i.e.,  ) mode has a right-hand side that rises above zero. It follows that only the

) mode has a right-hand side that rises above zero. It follows that only the  neoclassical tearing mode is is potentially unstable.

(See Section 12.4.)

The critical island width above which the mode is triggered (i.e., the smaller zero-crossing of the right-hand side) is about 1%

of the plasma minor radius. The saturated island width (i.e., the larger zero-crossing of the right-hand side) is about 17% of the plasma

minor radius.

neoclassical tearing mode is is potentially unstable.

(See Section 12.4.)

The critical island width above which the mode is triggered (i.e., the smaller zero-crossing of the right-hand side) is about 1%

of the plasma minor radius. The saturated island width (i.e., the larger zero-crossing of the right-hand side) is about 17% of the plasma

minor radius.