Next: Stabilization via RF-Driven Current Up: Neoclassical Tearing Modes Previous: Island Rotation Frequency Contents

,

,

,

,

(see Section 11.10),

(see Section 11.10),

[see Equation (2.217)],

[see Equation (2.217)],

[see Equation (2.243)], and

[see Equation (2.243)], and

[see Equation (2.244)].

Moreover,

[see Equation (2.244)].

Moreover,  is the resistive diffusion time [see Equation (5.49)],

is the resistive diffusion time [see Equation (5.49)],  a dimensionless measure of the electron temperature gradient at the rational surface [see Equation (4.3)],

a dimensionless measure of the electron temperature gradient at the rational surface [see Equation (4.3)],

the safety-factor at the rational surface [see Equation (3.2)],

the safety-factor at the rational surface [see Equation (3.2)],

the inverse aspect-ratio at the

rational surface [see Equation (3.18)],

the inverse aspect-ratio at the

rational surface [see Equation (3.18)],

a dimensionless measure of the plasma pressure at the rational surface [see Equations (4.65) and (4.66)],

a dimensionless measure of the plasma pressure at the rational surface [see Equations (4.65) and (4.66)],

the magnetic shear-length at the rational surface [see Equation (5.27)],

the magnetic shear-length at the rational surface [see Equation (5.27)],  the effective pressure gradient scale-length at the rational surface [see Equation (8.35)],

the effective pressure gradient scale-length at the rational surface [see Equation (8.35)],  the magnetic curvature length at the rational

surface [see Equation (11.57)], and

the magnetic curvature length at the rational

surface [see Equation (11.57)], and  the ion sound radius [see Equation (4.75)].

the ion sound radius [see Equation (4.75)].

The first term on the right-hand side of Equation (11.149) is the linear tearing stability index,

[11]. A classical (i.e., non-neoclassical) tearing mode is

unstable when

[11]. A classical (i.e., non-neoclassical) tearing mode is

unstable when

, and stable otherwise [30]. The free energy that drives a classical tearing mode is derived from equilibrium current

gradients within the plasma. (See Chapter 3.)

, and stable otherwise [30]. The free energy that drives a classical tearing mode is derived from equilibrium current

gradients within the plasma. (See Chapter 3.)

The second term on the right-hand side of Equation (11.149) is a stabilizing (i.e., negative) saturation term that prevents an unstable classical tearing mode from growing indefinitely [13].

The third term on the right-hand side of Equation (11.149) is a destabilizing (i.e., positive) term that is due to the loss of the bootstrap current within the magnetic separatrix of the island chain consequent on the flattening of the plasma pressure profile in this region [3].

The fourth term on the right-hand side of Equation (11.149) is a stabilizing term due to magnetic field-line curvature [14,20]. Note that this term also depends crucially on the flattening of the pressure profile within the magnetic separatrix.

The final term on the right-hand side of Equation (11.149) represents the stabilizing effect of the ion polarization current induced in the vicinity of the rational surface when the ion fluid is diverted around the island chain's magnetic separatrix [6,33,34,35]. Note that the polarization term is stabilizing because it is generally the case that

|

(12.19) |

on the separatrix, indicating that the polarization term is unlikely to survive if

the island width falls below

on the separatrix, indicating that the polarization term is unlikely to survive if

the island width falls below  .

Note, finally, that our polarization term does not exhibit the so-called neoclassical enhancement of inertia [17,34] [according to which it would be a

factor

.

Note, finally, that our polarization term does not exhibit the so-called neoclassical enhancement of inertia [17,34] [according to which it would be a

factor

larger]. As was shown in Reference [8], the neoclassical enhancement of inertia is only

operative when the neoclassical ion poloidal flow-damping term is the dominant term in the ion equation of parallel motion. However, as is clear from the

estimates made in the previous chapter, this is not likely to be the case in a tokamak fusion reactor.

larger]. As was shown in Reference [8], the neoclassical enhancement of inertia is only

operative when the neoclassical ion poloidal flow-damping term is the dominant term in the ion equation of parallel motion. However, as is clear from the

estimates made in the previous chapter, this is not likely to be the case in a tokamak fusion reactor.

Given that the the plasma pressure profile is only flattened within the separatrix of the magnetic island chain when

, and that the bootstrap, curvature, and polarization terms depend crucially on this flattening, it is conventional to modify Equation (12.15) as follows [7,21,24]:

, and that the bootstrap, curvature, and polarization terms depend crucially on this flattening, it is conventional to modify Equation (12.15) as follows [7,21,24]:

, and

, and  is defined in Equation (8.84).

The fact that the bootstrap term scales as

is defined in Equation (8.84).

The fact that the bootstrap term scales as  at small island width, whereas the curvature term scales as

at small island width, whereas the curvature term scales as  , can be established analytically [7,24].

The small-island-width behavior of the polarization term is a guess (that is irrelevant because the term turns out to be negligible).

Other modifications are possible. For instance, if the island width falls below the ion banana width then we would expect the ion contribution to the

destabilizing bootstrap term to disappear (because the trapped ions would average over the flattening of the pressure profile within the separatrix, so there would be no

reduction in the ion contribution to the bootstrap current in this region) [26].

, can be established analytically [7,24].

The small-island-width behavior of the polarization term is a guess (that is irrelevant because the term turns out to be negligible).

Other modifications are possible. For instance, if the island width falls below the ion banana width then we would expect the ion contribution to the

destabilizing bootstrap term to disappear (because the trapped ions would average over the flattening of the pressure profile within the separatrix, so there would be no

reduction in the ion contribution to the bootstrap current in this region) [26].

We can write the generalized Rutherford equation in the form

where and ,

,

,

Here,

,

Here,  is the plasma minor radius.

is the plasma minor radius.

![\includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{Chapter12/Figure12_2.eps}](img3712.png) |

Table 12.1 shows estimates for the various dimensionless parameters that characterize the right-hand side of the generalized Rutherford equation, (12.22), for the case of a

low-field and a high-field tokamak fusion reactor. (See Chapter 1.) These estimates are made using the following assumptions:

(low-field) or

(low-field) or

(high-field),

(high-field),

,

,

,

,

(where

(where  and

and  are the deuteron and triton masses, respectively),

are the deuteron and triton masses, respectively),

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

, and

, and

. The plasma equilibrium is

assumed to be of the Wesson type with

. The plasma equilibrium is

assumed to be of the Wesson type with  ,

,  , and

, and  . (See Section 9.4.) It can be seen, from the table, that the parameters in the generalized Rutherford equation all take the

same values for a low-field and a high-field reactor, apart from the critical normalized island width above which the plasma pressure is

flattened within the island chain's magnetic separatrix,

. (See Section 9.4.) It can be seen, from the table, that the parameters in the generalized Rutherford equation all take the

same values for a low-field and a high-field reactor, apart from the critical normalized island width above which the plasma pressure is

flattened within the island chain's magnetic separatrix,  , which is smaller in the former reactor type.

, which is smaller in the former reactor type.

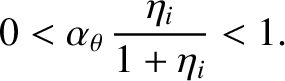

Figure 12.2 shows the various terms in the right-hand side of the generalized Rutherford equation, (12.22), plotted as functions of the normalized island width,  , for a low-field

and a high-field tokamak fusion reactor (using the parameters given in Table 12.1). It can be seen that the destabilizing bootstrap term is the dominant term. Moreover, the stabilizing curvature term is much smaller than the bootstrap term, but is important at small island widths. Furthermore, the stabilizing saturation term is only important at large island widths. Finally, the stabilizing polarization term is completely negligible (because there is

no neoclassical enhancement of inertia). It is clear that a high-field

tokamak fusion reactor is slightly less susceptible to a neoclassical tearing mode than a low-field reactor (because the destabilizing bootstrap term is smaller in the former case).

, for a low-field

and a high-field tokamak fusion reactor (using the parameters given in Table 12.1). It can be seen that the destabilizing bootstrap term is the dominant term. Moreover, the stabilizing curvature term is much smaller than the bootstrap term, but is important at small island widths. Furthermore, the stabilizing saturation term is only important at large island widths. Finally, the stabilizing polarization term is completely negligible (because there is

no neoclassical enhancement of inertia). It is clear that a high-field

tokamak fusion reactor is slightly less susceptible to a neoclassical tearing mode than a low-field reactor (because the destabilizing bootstrap term is smaller in the former case).

![\includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{Chapter12/Figure12_3.eps}](img3715.png) |

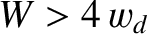

Figure 12.3 shows the function

calculated for an

calculated for an  /

/ tearing mode (

tearing mode ( is the poloidal mode number, whereas

is the poloidal mode number, whereas  is the toroidal mode number) in a low-field tokamak fusion reactor (using the parameters given in the left-hand column of Table 12.1) on the assumption that the linear tearing stability index

takes the value

is the toroidal mode number) in a low-field tokamak fusion reactor (using the parameters given in the left-hand column of Table 12.1) on the assumption that the linear tearing stability index

takes the value

. The fact that

. The fact that

implies that the classical 2/1 tearing mode is stable. On the other hand, as is clear from the figure,

the neoclassical 2/1 tearing mode is potentially unstable because there exists a range of island width for which

implies that the classical 2/1 tearing mode is stable. On the other hand, as is clear from the figure,

the neoclassical 2/1 tearing mode is potentially unstable because there exists a range of island width for which

. Now,

according to Equation (12.21), the roots of

. Now,

according to Equation (12.21), the roots of

correspond to possible steady-state island widths. There are two such roots shown in the figure, marked with and X and an O. The smaller

root (marked with an X) corresponds to a dynamically unstable equilibrium (because

correspond to possible steady-state island widths. There are two such roots shown in the figure, marked with and X and an O. The smaller

root (marked with an X) corresponds to a dynamically unstable equilibrium (because

), whereas the larger

root (marked with an O) corresponds to a dynamically stable equilibrium (because

), whereas the larger

root (marked with an O) corresponds to a dynamically stable equilibrium (because

). In fact, the smaller root specifies

a “seed” island width that must be exceeded in order to trigger the neoclassical tearing mode, whereas the larger root corresponds to the mode's final

saturated island width [21]. It can be seen that, in the example shown in the figure, the seed island width is about 0.2% of the plasma minor radius,

whereas the final saturated island width is about 11% of the minor radius.

). In fact, the smaller root specifies

a “seed” island width that must be exceeded in order to trigger the neoclassical tearing mode, whereas the larger root corresponds to the mode's final

saturated island width [21]. It can be seen that, in the example shown in the figure, the seed island width is about 0.2% of the plasma minor radius,

whereas the final saturated island width is about 11% of the minor radius.