Next: Neoclassical Tearing Modes Up: Toroidal Tearing Modes Previous: Nonlinear Calculation Contents

tearing mode that reconnects magnetic flux principally at a given rational surface

in our example tokamak discharge generates comparatively small reconnected fluxes at the other rational surfaces, as

a consequence of sheared plasma rotation. However, the small, but nonzero, reconnected fluxes driven at the other surfaces give rise to

localized electromagnetic torques. [See Equations (14.69) and (14.70).] In principle, such torques can modify the plasma

rotation, and may even lead to the collapse of the rotation shear that is responsible for the strong shielding of different rational

surfaces from one another [14]. Let us investigate this effect.

tearing mode that reconnects magnetic flux principally at a given rational surface

in our example tokamak discharge generates comparatively small reconnected fluxes at the other rational surfaces, as

a consequence of sheared plasma rotation. However, the small, but nonzero, reconnected fluxes driven at the other surfaces give rise to

localized electromagnetic torques. [See Equations (14.69) and (14.70).] In principle, such torques can modify the plasma

rotation, and may even lead to the collapse of the rotation shear that is responsible for the strong shielding of different rational

surfaces from one another [14]. Let us investigate this effect.

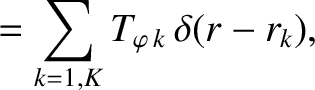

We shall adopt model plasma equations of poloidal and toroidal angular motion that are analogous to those introduced in Section 3.14. Let us write

|

(14.153) |

|

(14.154) |

is the flux-surface label introduced in Section 14.2. Moreover,

is the flux-surface label introduced in Section 14.2. Moreover,

and

and

are the majority ion poloidal and toroidal angular velocity profiles, respectively. Furthermore,

are the majority ion poloidal and toroidal angular velocity profiles, respectively. Furthermore,

and

and

are the majority ion poloidal and toroidal angular velocity profiles, respectively, in the absence of electromagnetic torques at the rational surfaces,

whereas,

are the majority ion poloidal and toroidal angular velocity profiles, respectively, in the absence of electromagnetic torques at the rational surfaces,

whereas,

and

and

are the respective changes in these profiles induced by the electromagnetic torques.

The modifications to the angular velocity profiles are governed by poloidal and toroidal angular equations of motion that take the respective forms [8,16]:

are the respective changes in these profiles induced by the electromagnetic torques.

The modifications to the angular velocity profiles are governed by poloidal and toroidal angular equations of motion that take the respective forms [8,16]:

![$\displaystyle 4\pi^2\,R_0\left[\rho\,r^3\,\frac{\partial{\mit\Delta\Omega}_\the...

...rp\,i}\,r^3\,\frac{\partial{\mit\Delta\Omega}_\theta}{\partial r}\right)\right]$](img4427.png) |

|

(14.155) |

![$\displaystyle 4\pi^2\,R_0^{\,3}\left[\rho\,r\,\frac{\partial{\mit\Delta\Omega}_...

...erp\,i}\,r\,\frac{\partial{\mit\Delta\Omega}_\varphi}{\partial r}\right)\right]$](img4429.png) |

|

(14.156) |

|

|

(14.157) |

|

|

(14.158) |

and

and

are defined in Equations (A.23) and (A.53), respectively, is the poloidal flow-damping time

profile. Equation (14.159) is a generalization of Equation (2.332) that does not assume that the faction of trapped particles is

small, or that the plasma is in the banana collisionality regime. Finally, the electromagnetic torques,

are defined in Equations (A.23) and (A.53), respectively, is the poloidal flow-damping time

profile. Equation (14.159) is a generalization of Equation (2.332) that does not assume that the faction of trapped particles is

small, or that the plasma is in the banana collisionality regime. Finally, the electromagnetic torques,

and

and

, are specified in Equations (14.69) and (14.70),

respectively.

, are specified in Equations (14.69) and (14.70),

respectively.

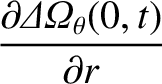

Following the analysis of Section 3.15, it is convenient to write

where and

Now, the modified angular velocity profiles,

and

and

, are mostly localized in the

vicinity of the

, are mostly localized in the

vicinity of the  th rational surface. Hence, it is a

reasonable approximation to express Equations (14.162) and (14.163) in the simplified forms [16]

th rational surface. Hence, it is a

reasonable approximation to express Equations (14.162) and (14.163) in the simplified forms [16]

![$\displaystyle 4\pi^{2}\,R_0\left[\rho_k\,r^{3}\,\frac{\partial{\mit\Delta\Omega...

...r^{3}\,\frac{\partial{\mit\Delta\Omega}_{\theta\,k}}{\partial r}\right)

\right]$](img4451.png) |

|

(14.166) |

![$\displaystyle 4\pi^{2}\,R_0^{\,3}\left[\rho_k\,r\,\frac{\partial{\mit\Delta\Ome...

...t(

r\,\frac{\partial{\mit\Delta\Omega}_{\varphi\,k}}{\partial r}\right) \right]$](img4452.png) |

|

(14.167) |

,

,

, and

, and

.

where

Here,

.

where

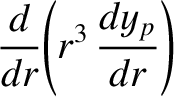

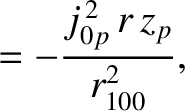

Here,  is a Bessel function, and

is a Bessel function, and  denotes its

denotes its  th zero [1]. Note that

Equations (14.168)–(14.171) automatically satisfy the boundary conditions (14.164) and (14.165).

th zero [1]. Note that

Equations (14.168)–(14.171) automatically satisfy the boundary conditions (14.164) and (14.165).

It is easily demonstrated that [33]

|

|

(14.172) |

|

|

(14.173) |

|

![$\displaystyle = \frac{r_{100}^{4}}{2}\,[J_2(j_{1p})]^{\,2}\,\delta_{pq},$](img4465.png) |

(14.174) |

|

![$\displaystyle = \frac{r_{100}^{2}}{2}\,[J_1(j_{0p})]^{\,2}\,\delta_{pq}.$](img4467.png) |

(14.175) |

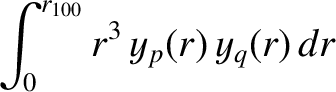

Equations (14.69), (14.70), and (14.166)–(14.175) yield

Here, The values of ,

,

,

,

, and

, and

at the

at the  rational surfaces in our example

tokamak discharge are specified in Table 14.8.

Incidentally, Equations (14.176) and (14.177) are the toroidal generalizations of the cylindrical equations (3.190) and (3.191), respectively.

rational surfaces in our example

tokamak discharge are specified in Table 14.8.

Incidentally, Equations (14.176) and (14.177) are the toroidal generalizations of the cylindrical equations (3.190) and (3.191), respectively.

Let us define the frequency shifts that develop at the various rational surfaces in the plasma in response to the electromagnetic torques:

|

(14.183) |

Consider an  tearing mode that reconnects magnetic flux principally at the

tearing mode that reconnects magnetic flux principally at the  th rational surface in our example tokamak discharge.

Let

th rational surface in our example tokamak discharge.

Let

be the normalized magnetic flux reconnected at the

be the normalized magnetic flux reconnected at the  th surface, and let us suppose that

th surface, and let us suppose that

is sufficiently large

that the plasma response at the

is sufficiently large

that the plasma response at the  th surface lies in the nonlinear regime. Because of the assumed strong shielding at the

other rational surfaces in the plasma, we expect the plasma responses at these surfaces to lie in the linear regime.

th surface lies in the nonlinear regime. Because of the assumed strong shielding at the

other rational surfaces in the plasma, we expect the plasma responses at these surfaces to lie in the linear regime.

We can determine the normalized reconnected magnetic fluxes,

, driven at the other rational surfaces from Equations (14.119), (14.123),

(14.146), and (14.182).

We find that

, driven at the other rational surfaces from Equations (14.119), (14.123),

(14.146), and (14.182).

We find that

|

(14.186) |

. Hence,

for

. Hence,

for  ,

where

,

where

The normalized electromagnetic torque acting at the  th (where

th (where  ) rational surface is

) rational surface is

th rational surface is obtained from

angular momentum conservation (see Section 14.11):

th rational surface is obtained from

angular momentum conservation (see Section 14.11):

According to Equation (14.151), the frequency shift at the  th rational surface modifies the real frequency of the

tearing mode. In fact,

th rational surface modifies the real frequency of the

tearing mode. In fact,

![\includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{Chapter14/Figure14_4.eps}](img4514.png)

|

The normalized linear layer response indicies,

(where

(where  ), that appear in Equation (14.188), are functions

of nine normalized layer parameters. (See Table 14.3.) Two of these parameters,

), that appear in Equation (14.188), are functions

of nine normalized layer parameters. (See Table 14.3.) Two of these parameters,  and

and  , are modified

by the frequency shifts induced by the electromagnetic torques. In fact, it is clear from Equations (14.130), (14.131),

(14.185), and (14.191) that

, are modified

by the frequency shifts induced by the electromagnetic torques. In fact, it is clear from Equations (14.130), (14.131),

(14.185), and (14.191) that

indicates a quantity that is unaffected by the electromagnetic torques.

indicates a quantity that is unaffected by the electromagnetic torques.

Equations (14.176), (14.177), (14.184), (14.188)–(14.190), (14.192), (14.193)—together with the numerical solution of the Riccati differential

equation, (5.121), subject to the boundary conditions (5.122) and (5.123), which determines the

—

form a closed set of equations that allow us to determine the reconnected magnetic fluxes driven at the various rational surfaces in our example tokamak

discharge by a tearing mode that reconnects magnetic flux primarily at the

—

form a closed set of equations that allow us to determine the reconnected magnetic fluxes driven at the various rational surfaces in our example tokamak

discharge by a tearing mode that reconnects magnetic flux primarily at the  th rational surface. The only free parameter in the model

is the normalized reconnected magnetic flux at the

th rational surface. The only free parameter in the model

is the normalized reconnected magnetic flux at the  th rational surface,

th rational surface,

.

.

Consider an  tearing mode in our example tokamak discharge that reconnects magnetic

flux principally at the

tearing mode in our example tokamak discharge that reconnects magnetic

flux principally at the  (i.e.,

(i.e.,  ) rational surface. Such a mode could represent an

) rational surface. Such a mode could represent an  neoclassical

tearing mode. It is helpful to define the natural frequencies at the various

neoclassical

tearing mode. It is helpful to define the natural frequencies at the various  rational surfaces in the plasma:

rational surfaces in the plasma:

|

|

(14.194) |

|

|

(14.195) |

, 3, 4, where

, 3, 4, where

and

and

are specified in Table 14.5. Here, we are taking into account the fact that the plasma response at the

are specified in Table 14.5. Here, we are taking into account the fact that the plasma response at the  rational surface lies

in the nonlinear regime (because the

rational surface lies

in the nonlinear regime (because the  island width is assumed to be greater than the corresponding linear layer width),

whereas the plasma responses at the other rational surfaces lie in the linear regime (because the driven island

widths are assumed to be less than the corresponding linear layer widths). Moreover, we are also taking into account the

modifications to the natural frequencies generated by the electromagnetic torques that develop at the rational surfaces.

Recall that the natural frequency at a given rational surface is the preferred rotation frequency of reconnected

magnetic flux at that surface.

island width is assumed to be greater than the corresponding linear layer width),

whereas the plasma responses at the other rational surfaces lie in the linear regime (because the driven island

widths are assumed to be less than the corresponding linear layer widths). Moreover, we are also taking into account the

modifications to the natural frequencies generated by the electromagnetic torques that develop at the rational surfaces.

Recall that the natural frequency at a given rational surface is the preferred rotation frequency of reconnected

magnetic flux at that surface.

![\includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{Chapter14/Figure14_5.eps}](img4527.png)

|

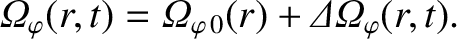

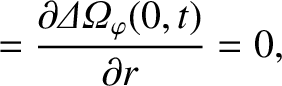

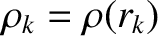

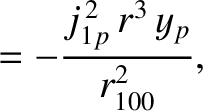

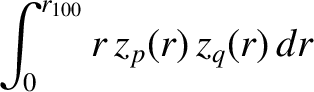

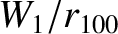

Figure 14.4 shows the  natural frequencies in our example tokamak

discharge calculated as functions of the normalized

natural frequencies in our example tokamak

discharge calculated as functions of the normalized  magnetic island width,

magnetic island width,

,

in a simulation in which the island width is slowly ramped up. This calculation is made using the

previously mentioned closed set of equations, as well as the data given in Tables 14.1, 14.2, 14.3, 14.5, and 14.8.

It can be seen that if

,

in a simulation in which the island width is slowly ramped up. This calculation is made using the

previously mentioned closed set of equations, as well as the data given in Tables 14.1, 14.2, 14.3, 14.5, and 14.8.

It can be seen that if

lies close to zero then the natural frequencies all take the unperturbed values specified in

Table 14.5. On the other hand, as

lies close to zero then the natural frequencies all take the unperturbed values specified in

Table 14.5. On the other hand, as

increases, the electromagnetic torques that develop at the rational

surfaces modify the natural frequencies. In particular, the torques cause the

increases, the electromagnetic torques that develop at the rational

surfaces modify the natural frequencies. In particular, the torques cause the  natural frequency,

natural frequency,

, and the

, and the

natural frequency,

natural frequency,

, to approach one another. At a critical value of

, to approach one another. At a critical value of

, which is approximately 0.41, the two natural

frequencies suddenly snap together, indicating a sudden loss of shielding at the

, which is approximately 0.41, the two natural

frequencies suddenly snap together, indicating a sudden loss of shielding at the  rational surface [14].

rational surface [14].

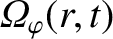

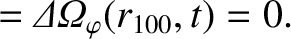

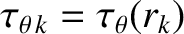

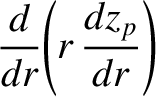

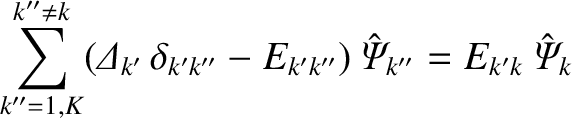

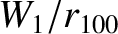

The aforementioned sudden loss of shielding

is illustrated in Figure 14.5, which shows the driven normalized magnetic island widths at the  , 4, and 5 rational surfaces in our example

discharge as functions

of the normalized

, 4, and 5 rational surfaces in our example

discharge as functions

of the normalized  island width. It can be seen that, prior to the loss of shielding, comparatively narrow magnetic island chains are

driven at the

island width. It can be seen that, prior to the loss of shielding, comparatively narrow magnetic island chains are

driven at the  , 4, and 5 rational surfaces. However, as soon as the shielding at the

, 4, and 5 rational surfaces. However, as soon as the shielding at the  rational surface is lost, there is a

very significant increase in the width of the magnetic island chain driven at the

rational surface is lost, there is a

very significant increase in the width of the magnetic island chain driven at the  surface.

surface.

![\includegraphics[width=\textwidth]{Chapter14/Figure14_6.eps}](img4533.png)

|

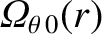

Finally, Figure 14.6 shows the normalized electromagnetic torques that develop at the  rational surfaces in our example discharge close to the time at

which shielding is lost at the

rational surfaces in our example discharge close to the time at

which shielding is lost at the  rational surface. It can be seen that the sudden loss of shielding is due to comparatively large transient

electromagnetic torques that develop at the

rational surface. It can be seen that the sudden loss of shielding is due to comparatively large transient

electromagnetic torques that develop at the  and

and  rational surfaces, and drive the corresponding natural frequencies together.

rational surfaces, and drive the corresponding natural frequencies together.

The calculation that we have just performed indicates that the shielding of  rational surfaces from one another, as a consequence of

sheared rotation, in our example tokamak discharge is a very robust effect. In fact, the shielding only breaks down when a tearing mode

grows to a sufficient amplitude that the width of its magnetic island chain becomes a substantial fraction of the plasma minor radius. However,

when shielding breaks down, it does so in a sudden and catastrophic manner [14]. In fact, in our example calculation, the loss of

shielding at the

rational surfaces from one another, as a consequence of

sheared rotation, in our example tokamak discharge is a very robust effect. In fact, the shielding only breaks down when a tearing mode

grows to a sufficient amplitude that the width of its magnetic island chain becomes a substantial fraction of the plasma minor radius. However,

when shielding breaks down, it does so in a sudden and catastrophic manner [14]. In fact, in our example calculation, the loss of

shielding at the  rational surface drives a magnetic island chain at that surface whose width is sufficient that the chain

would overlap with the chain at the

rational surface drives a magnetic island chain at that surface whose width is sufficient that the chain

would overlap with the chain at the  rational surface, leading to the sudden destruction of magnetic flux-surfaces [26], which could

quite conceivably trigger a disruption [7].

rational surface, leading to the sudden destruction of magnetic flux-surfaces [26], which could

quite conceivably trigger a disruption [7].