Next: Capacitors Up: Electrostatic Fields Previous: Ohm's Law

,

acting around each loop (unless the conductor is a

superconductor, with

,

acting around each loop (unless the conductor is a

superconductor, with  ). However, we know that in a steady state

). However, we know that in a steady state

|

(2.123) |

. [See Equation (2.24).] This proves that a steady-state emf acting around

a closed loop inside a conductor is impossible. The only other alternative is

everywhere inside the conductor. It immediately follows from the field equation

. [See Equation (2.24).] This proves that a steady-state emf acting around

a closed loop inside a conductor is impossible. The only other alternative is

everywhere inside the conductor. It immediately follows from the field equation

[see Equation (2.54)]

that

[see Equation (2.54)]

that

|

(2.125) |

Now, the difference in scalar potential between

two points  and

and  is simply

is simply

and

and  both lie inside the same conductor

then it is clear from Equations (2.124) and (2.126) that the potential difference between

both lie inside the same conductor

then it is clear from Equations (2.124) and (2.126) that the potential difference between  and

and

is zero. This is true no matter where

is zero. This is true no matter where  and

and  are situated inside the

conductor, so we conclude that the scalar potential must be

uniform inside a conductor.

One corollary of this fact is that the surface of a conductor is

an equipotential (i.e.,

are situated inside the

conductor, so we conclude that the scalar potential must be

uniform inside a conductor.

One corollary of this fact is that the surface of a conductor is

an equipotential (i.e.,  constant) surface.

constant) surface.

We have demonstrated that the electric field inside a conductor is zero. We can also demonstrate that the field within an empty cavity lying inside a conductor is

zero, provided that there are no charges within the cavity. Let  be the cavity in question, and let

be the cavity in question, and let  be its bounding

surface. Because there are no electric charges within the cavity, the electric potential,

be its bounding

surface. Because there are no electric charges within the cavity, the electric potential,  , inside the cavity

satisfies

, inside the cavity

satisfies

corresponds to the inner surface of the conductor that surrounds the

cavity,

corresponds to the inner surface of the conductor that surrounds the

cavity,  is an equipotential surface. In other words, the electric potential on

is an equipotential surface. In other words, the electric potential on  takes a constant value,

takes a constant value,  (say).

So, we need to solve a simplified version of Poisson's equation, (2.127), throughout

(say).

So, we need to solve a simplified version of Poisson's equation, (2.127), throughout  , subject to the

boundary condition that

, subject to the

boundary condition that

on

on  . One obvious solution to this problem is

. One obvious solution to this problem is

throughout

throughout  and on

and on  . However, we showed in Section 2.1.10 that the solutions to Poisson's equation in a volume

surrounded by a surface on which the potential is specified are unique. Thus,

. However, we showed in Section 2.1.10 that the solutions to Poisson's equation in a volume

surrounded by a surface on which the potential is specified are unique. Thus,

throughout

throughout  and on

and on  is the only solution to the problem. It follows that the electric field

is the only solution to the problem. It follows that the electric field

is

zero throughout the cavity. [See Equation (2.17).]

is

zero throughout the cavity. [See Equation (2.17).]

We have shown that if a charge-free cavity is completely enclosed by a conductor then no stationary distribution of charges outside the conductor can ever produce any electric fields inside the cavity. It follows that we can shield a sensitive piece of electrical equipment from stray external electric fields by placing it inside a metal can. In fact, a wire mesh cage will do, as long as the mesh spacing is not too wide. Such a cage is known as a Faraday cage.

Consider a small region lying on the surface of a conductor. Suppose that

the local surface electric charge density is  , and that the electric field just outside

the conductor is

, and that the electric field just outside

the conductor is  . Note that this field must be directed normal

to the surface of the conductor. Any parallel component would be shorted out

by surface currents. Another way of saying this is that the surface of a conductor

is an equipotential. We know that

. Note that this field must be directed normal

to the surface of the conductor. Any parallel component would be shorted out

by surface currents. Another way of saying this is that the surface of a conductor

is an equipotential. We know that

is always perpendicular to

an equipotential (see Section A.18), so

is always perpendicular to

an equipotential (see Section A.18), so

[see Equation (2.17)] must be locally perpendicular

to a conducting surface. Let us use Gauss's law [see Equation (2.58)],

[see Equation (2.17)] must be locally perpendicular

to a conducting surface. Let us use Gauss's law [see Equation (2.58)],

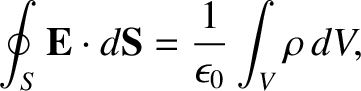

|

(2.128) |

is a so-called Gaussian pill-box. See Figure 2.5. A Gaussian pill-box is a volume of space whose shape is similar to an old-fashioned pill-box (or a modern pizza box).

Let the two flat ends of the pill-box be aligned parallel to the surface of the conductor,

with the surface running between them, and let the comparatively short sides be perpendicular to the

surface.

It is clear that

is a so-called Gaussian pill-box. See Figure 2.5. A Gaussian pill-box is a volume of space whose shape is similar to an old-fashioned pill-box (or a modern pizza box).

Let the two flat ends of the pill-box be aligned parallel to the surface of the conductor,

with the surface running between them, and let the comparatively short sides be perpendicular to the

surface.

It is clear that  is parallel to the sides of the box, so the sides

make no contribution to the surface integral. The end of the box that lies

inside the conductor also makes no contribution,

because

is parallel to the sides of the box, so the sides

make no contribution to the surface integral. The end of the box that lies

inside the conductor also makes no contribution,

because

inside a conductor. Thus, the only non-zero contribution to the

surface integral comes from the end lying in free space. This contribution

is simply

inside a conductor. Thus, the only non-zero contribution to the

surface integral comes from the end lying in free space. This contribution

is simply

, where

, where  denotes an outward pointing (from the

conductor) normal

electric field, and

denotes an outward pointing (from the

conductor) normal

electric field, and  is the cross-sectional area of the box.

The charge enclosed

by the box is simply

is the cross-sectional area of the box.

The charge enclosed

by the box is simply  , from the definition of a surface charge density.

Thus, Gauss's law yields

as the relationship between the normal electric field immediately outside a conductor

and the surface charge density.

, from the definition of a surface charge density.

Thus, Gauss's law yields

as the relationship between the normal electric field immediately outside a conductor

and the surface charge density.

Let us look at the electric field generated by a sheet charge distribution

a little more carefully. Suppose that the charge per unit area is  .

By symmetry, we expect the field generated below the sheet to be the mirror image

of that above the sheet (at least, locally). Thus, if apply Gauss's law to

a pill-box of cross-sectional area

.

By symmetry, we expect the field generated below the sheet to be the mirror image

of that above the sheet (at least, locally). Thus, if apply Gauss's law to

a pill-box of cross-sectional area  , as shown in Figure 2.6, then the

two ends both contribute

, as shown in Figure 2.6, then the

two ends both contribute

to the surface integral, where

to the surface integral, where

is the normal

electric field generated above and below the sheet. The charge enclosed

by the pill-box is just

is the normal

electric field generated above and below the sheet. The charge enclosed

by the pill-box is just  . Thus, Gauss's law yields

a symmetric electric field

. Thus, Gauss's law yields

a symmetric electric field

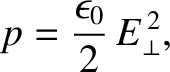

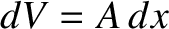

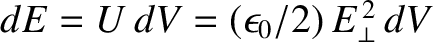

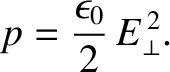

Making use of Equations (2.131) and (2.133), the electrostatic pressure acting at the surface of a conductor can also be written

|

(2.134) |

is the electric field-strength immediately above the surface of the conductor.

Note that, according to the previous formula, the electrostatic pressure is equivalent

to the energy density of the electric field immediately outside the conductor. [See Equation (2.84).]

This is not a coincidence. Suppose that the conductor expands normally by an average

distance

is the electric field-strength immediately above the surface of the conductor.

Note that, according to the previous formula, the electrostatic pressure is equivalent

to the energy density of the electric field immediately outside the conductor. [See Equation (2.84).]

This is not a coincidence. Suppose that the conductor expands normally by an average

distance  , due to the electrostatic pressure. The electric field is excluded

from the region into which the conductor expands. The volume of this region

is

, due to the electrostatic pressure. The electric field is excluded

from the region into which the conductor expands. The volume of this region

is

, where

, where  is the surface area of the conductor. Thus, the energy

of the electric field decreases by an amount

is the surface area of the conductor. Thus, the energy

of the electric field decreases by an amount

,

where

,

where  is the energy density of the field. This decrease in energy can be

ascribed to the work that the field does on the conductor in order to make it expand.

This work is

is the energy density of the field. This decrease in energy can be

ascribed to the work that the field does on the conductor in order to make it expand.

This work is

, where

, where  is the force per unit area that the field exerts

on the conductor. Thus,

is the force per unit area that the field exerts

on the conductor. Thus,  , from energy conservation, giving

, from energy conservation, giving

|

(2.135) |