Electrostatic Energy

Consider a collection of  static point electric charges

static point electric charges  located at displacements

located at displacements

.

What is the electrostatic energy stored in such a collection? In other words, how much work would we have to perform in order to assemble

the charges, starting from an initial state in which they are all

at rest and very widely

separated?

.

What is the electrostatic energy stored in such a collection? In other words, how much work would we have to perform in order to assemble

the charges, starting from an initial state in which they are all

at rest and very widely

separated?

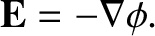

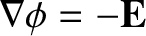

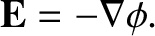

We know that a static electric field is conservative, and can consequently

be written in terms of

a scalar potential:

|

(2.65) |

[See Equation (2.17).]

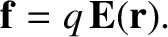

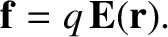

We also know that the electrical force acting on a charge  located at displacement

located at displacement  is

written

is

written

|

(2.66) |

[See Equation (2.10).]

The work that we would have to do against electrical forces in order to slowly

move the charge from point  to point

to point  is simply

is simply

![$\displaystyle W = \int_P^Q (-{\bf f}) \cdot d{\bf r} =- q \int_P^Q {\bf E} \cdo...

...bf r}

=q\int_P^Q \nabla\phi \cdot d{\bf r} = q \left[ \phi(Q) - \phi(P)\right],$](img1240.png) |

(2.67) |

where  is an element of the path taken between the two points. (See Section 1.3.2.)

The negative sign in the previous expression comes about because we would have to

exert a force

is an element of the path taken between the two points. (See Section 1.3.2.)

The negative sign in the previous expression comes about because we would have to

exert a force  on the charge, in order to counteract the force

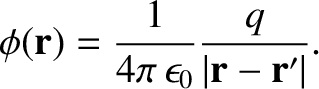

exerted by the electric field. Recall, finally, that the scalar potential field

generated by a point charge

on the charge, in order to counteract the force

exerted by the electric field. Recall, finally, that the scalar potential field

generated by a point charge  located at position

located at position  is

is

|

(2.68) |

[See Equation (2.21).]

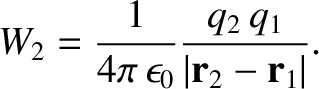

Let us build up our collection of charges one by one. It takes no work to bring the

first charge from infinity, because there is no electric field to fight against.

Let us clamp this charge in position at displacement  . In order to bring the

second charge into position at displacement

. In order to bring the

second charge into position at displacement  ,

we have to do work against the electric field

generated by the first charge. According to Equations (2.67) and (2.68),

this work is given by

,

we have to do work against the electric field

generated by the first charge. According to Equations (2.67) and (2.68),

this work is given by

|

(2.69) |

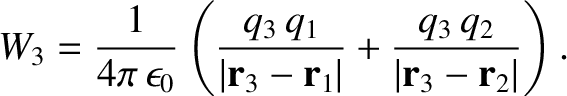

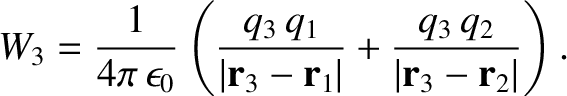

Let us now bring the third charge into position. Because electric fields

and scalar potentials are

superposable, the work done while moving the third charge from infinity to displacement  is simply the sum of the works done against the electric fields generated by

charges 1 and 2, taken in isolation:

is simply the sum of the works done against the electric fields generated by

charges 1 and 2, taken in isolation:

|

(2.70) |

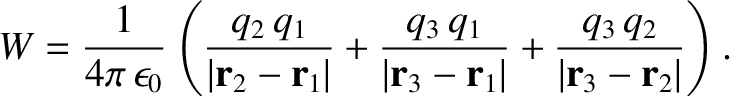

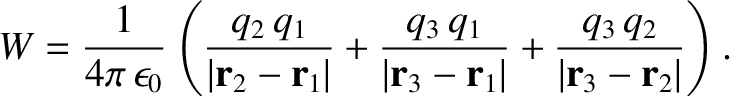

Thus, the total work done in assembling the collection of three charges is given by

|

(2.71) |

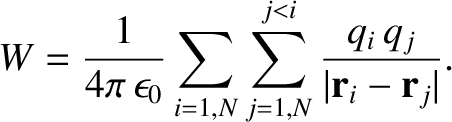

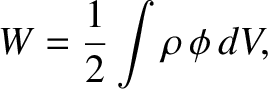

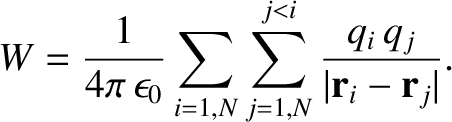

This result can easily be generalized to a collection of  charges:

charges:

|

(2.72) |

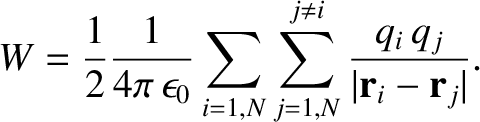

The restriction that  must be less than

must be less than  makes the previous summation

rather messy. If we were to sum without restriction (other than

makes the previous summation

rather messy. If we were to sum without restriction (other than  ) then

each pair of charges would be counted twice. It is convenient to do just

this, and then to divide the result by two. Thus, we obtain

) then

each pair of charges would be counted twice. It is convenient to do just

this, and then to divide the result by two. Thus, we obtain

|

(2.73) |

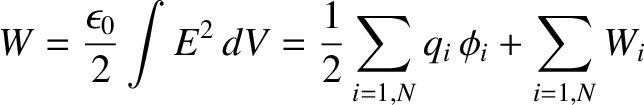

This is the electric potential energy (i.e., the difference between the total energy

and the kinetic energy) of a collection of point electric charges. We can think of this quantity as the

work required to bring stationary charges from infinity and assemble them in the

required formation. Alternatively, it is the kinetic energy that would

be released if the collection were dissolved, and the charges returned to infinity.

But where is this potential energy stored? Let us investigate further.

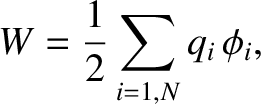

Equation (2.73) can be written

|

(2.74) |

where

|

(2.75) |

is the scalar potential experienced by the  th charge due to the other

charges in the distribution. [See Equation (2.20).]

th charge due to the other

charges in the distribution. [See Equation (2.20).]

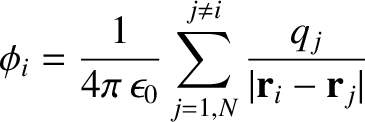

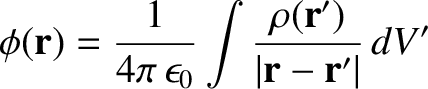

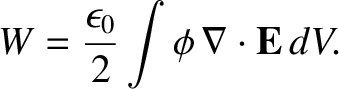

Let us now consider the potential energy of a continuous charge distribution.

It is tempting to write

|

(2.76) |

by analogy with Equations (2.74) and (2.75), where

|

(2.77) |

is the familiar scalar potential generated by a continuous charge distribution

of charge density

[see Equation (2.18)], and where the volume integrals are over all space.

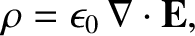

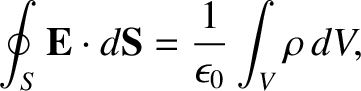

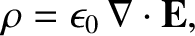

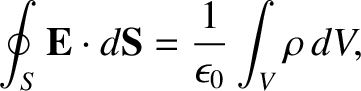

Let us try this scheme out. We know from Equation (2.54) that

[see Equation (2.18)], and where the volume integrals are over all space.

Let us try this scheme out. We know from Equation (2.54) that

|

(2.78) |

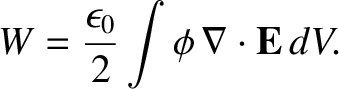

so Equation (2.76) can be written

|

(2.79) |

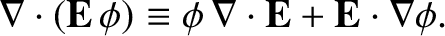

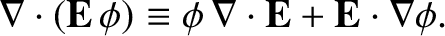

Now,

|

(2.80) |

(See Section A.24.)

However,

, so we obtain

, so we obtain

![$\displaystyle W = \frac{\epsilon_0}{2} \left[\int \nabla\cdot ({\bf E}\,\phi)\,dV

+

\int E^2\,dV\right]$](img1258.png) |

(2.81) |

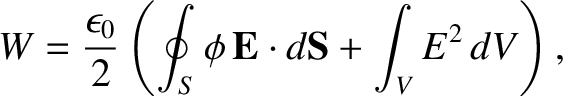

Application of the divergence theorem (see Section A.20) gives

|

(2.82) |

where  is some volume that encloses all of the charges, and

is some volume that encloses all of the charges, and  is its bounding

surface. Let us assume that

is its bounding

surface. Let us assume that  is a sphere, centered on the origin, and let

us take the limit in which the radius

is a sphere, centered on the origin, and let

us take the limit in which the radius  of this sphere goes to infinity.

We know that, in general, the electric field at large distances from a

bounded charge

distribution looks like the field of a point charge, and, therefore,

falls off like

of this sphere goes to infinity.

We know that, in general, the electric field at large distances from a

bounded charge

distribution looks like the field of a point charge, and, therefore,

falls off like  . Likewise, the potential falls off like

. Likewise, the potential falls off like  . (See Section 2.1.7.) However,

the surface area of the sphere increases like

. (See Section 2.1.7.) However,

the surface area of the sphere increases like  . Hence, it is clear that, in the

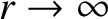

limit as

. Hence, it is clear that, in the

limit as

, the surface integral in Equation (2.82) falls off

like

, the surface integral in Equation (2.82) falls off

like  , and is consequently zero.

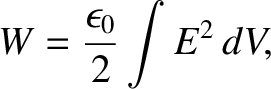

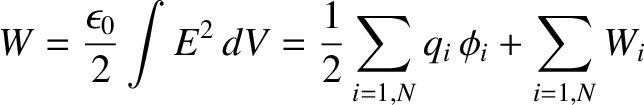

Thus, Equation (2.82) reduces to

, and is consequently zero.

Thus, Equation (2.82) reduces to

|

(2.83) |

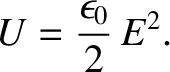

where the volume integral is over all space. This is a very interesting

result. It tells us that the potential energy of a continuous charge

distribution is stored in the electric field generated by that distribution. Of course, we now have to assume that

an electric field possesses an energy density

|

(2.84) |

Incidentally, the fact that an electric field possess an energy density demonstrates that it has a real physical existence, and

is not just an aid to the calculation of electrostatic forces.

We can easily check that Equation (2.83) is correct. Suppose that we have an electric

charge  that is uniformly distributed within a sphere of

radius

that is uniformly distributed within a sphere of

radius  centered on the origin. Let us imagine building up this charge distribution

from a succession of thin spherical layers of infinitesimal thickness. At each

stage, we gather a small amount of charge

centered on the origin. Let us imagine building up this charge distribution

from a succession of thin spherical layers of infinitesimal thickness. At each

stage, we gather a small amount of charge  from infinity, and spread it

over the surface of the sphere in a thin

layer extending from

from infinity, and spread it

over the surface of the sphere in a thin

layer extending from  to

to  . We continue this process until the final radius of the

sphere is

. We continue this process until the final radius of the

sphere is  . If

. If  is the sphere's charge when it has attained radius

is the sphere's charge when it has attained radius

then the work done in bringing a charge

then the work done in bringing a charge  to its surface is

to its surface is

|

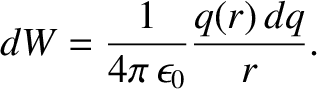

(2.85) |

This follows from Equation (2.69), because the electric field generated outside a spherical charge

distribution

is the same as that of a point charge  located at its geometric center

(

located at its geometric center

( ). (See Section 2.1.7.) If the constant charge density of the sphere is

). (See Section 2.1.7.) If the constant charge density of the sphere is

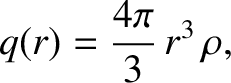

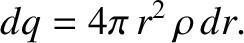

then

then

|

(2.86) |

and

|

(2.87) |

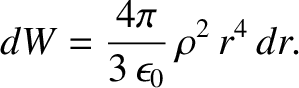

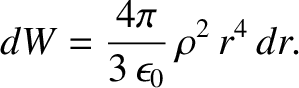

Thus, Equation (2.85) becomes

|

(2.88) |

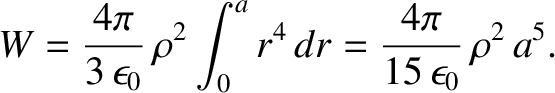

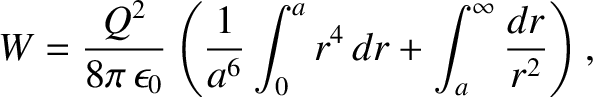

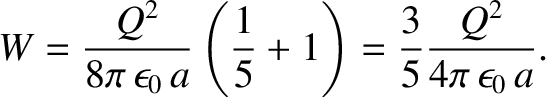

The total work needed to build up the sphere from zero radius to radius  is

plainly

is

plainly

|

(2.89) |

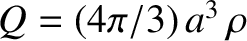

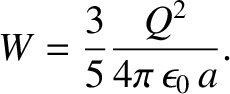

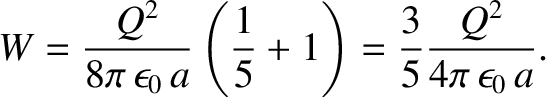

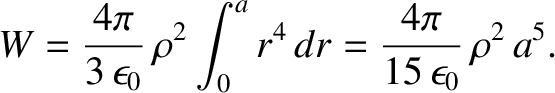

This can also be written in terms of the total charge

as

as

|

(2.90) |

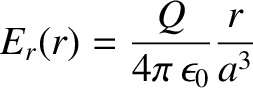

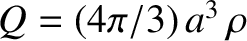

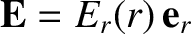

Now that we have evaluated the potential energy of a spherical charge distribution

by the direct method, let us work it out using Equation (2.83). We shall assume that the

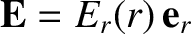

electric field is both radial and spherically symmetric, so that

. Here,

. Here,  is a standard spherical polar coordinate. (See Section A.23.) Application of Gauss's law,

is a standard spherical polar coordinate. (See Section A.23.) Application of Gauss's law,

|

(2.91) |

where  is a sphere of radius

is a sphere of radius  , centered on the origin, gives

, centered on the origin, gives

|

(2.92) |

for  , and

, and

|

(2.93) |

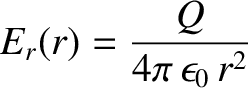

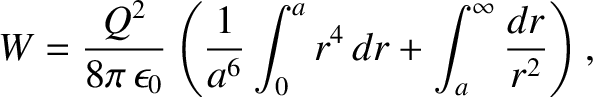

for  . Equations (2.83), (2.92), and (2.93) yield

. Equations (2.83), (2.92), and (2.93) yield

|

(2.94) |

which reduces to

|

(2.95) |

Thus, Equation (2.83) gives the correct answer.

The reason that we have checked Equation (2.83) so carefully is that, on close inspection,

it is found to be

inconsistent with Equation (2.74), from which it was supposedly derived.

For instance, the energy given by Equation (2.83) is manifestly positive definite, whereas

the energy given by Equation (2.74) can be negative (it is certainly negative for

a collection of two point charges of opposite sign). The

inconsistency was introduced into our analysis when we replaced Equation (2.75) by

Equation (2.77). In Equation (2.75), the self-interaction of the  th charge with its

own electric field is specifically excluded, whereas it is included in Equation (2.77). Thus,

the potential energies

(2.74) and (2.83) are different because in the former we start from

ready-made point charges, whereas in the latter we build up the whole

charge distribution from scratch. Hence, if we were to work out the

potential energy of a point charge distribution using Equation (2.83) then

we would obtain the energy (2.74) plus the energy required to assemble the

point charges. What is the energy required to assemble a point electric charge?

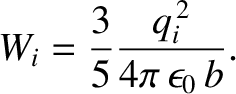

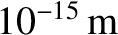

In fact, it is infinite. To see this, let us suppose, for the sake of argument, that

our point charges actually consist of electric charge uniformly distributed in small

spheres of radius

th charge with its

own electric field is specifically excluded, whereas it is included in Equation (2.77). Thus,

the potential energies

(2.74) and (2.83) are different because in the former we start from

ready-made point charges, whereas in the latter we build up the whole

charge distribution from scratch. Hence, if we were to work out the

potential energy of a point charge distribution using Equation (2.83) then

we would obtain the energy (2.74) plus the energy required to assemble the

point charges. What is the energy required to assemble a point electric charge?

In fact, it is infinite. To see this, let us suppose, for the sake of argument, that

our point charges actually consist of electric charge uniformly distributed in small

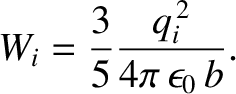

spheres of radius  . According to Equation (2.90), the energy required to assemble the

. According to Equation (2.90), the energy required to assemble the

th point charge is

th point charge is

|

(2.96) |

We can think of this as the self-energy of the  th charge.

Thus, we can write

th charge.

Thus, we can write

|

(2.97) |

which enables us to reconcile Equations (2.74) and (2.83). Unfortunately, if

our point charges really are point charges then

, and the

self-energy of each charge becomes infinite. Thus, the potential

energies predicted by Equations (2.74) and (2.83) differ by an infinite amount.

What does this all mean? We have to conclude that the idea of locating electrostatic

potential energy in the electric field runs into conceptual difficulties in the presence of point electric charges. One way out of this dilemma would be to

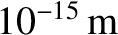

say that elementary electric charges, such as protons and electrons, are not point objects, but instead have finite spatial extents. Regrettably, although protons have finite spatial extents (of about

, and the

self-energy of each charge becomes infinite. Thus, the potential

energies predicted by Equations (2.74) and (2.83) differ by an infinite amount.

What does this all mean? We have to conclude that the idea of locating electrostatic

potential energy in the electric field runs into conceptual difficulties in the presence of point electric charges. One way out of this dilemma would be to

say that elementary electric charges, such as protons and electrons, are not point objects, but instead have finite spatial extents. Regrettably, although protons have finite spatial extents (of about

), electrons really do seem to be point objects.

), electrons really do seem to be point objects.

static point electric charges

static point electric charges  located at displacements

located at displacements

.

What is the electrostatic energy stored in such a collection? In other words, how much work would we have to perform in order to assemble

the charges, starting from an initial state in which they are all

at rest and very widely

separated?

.

What is the electrostatic energy stored in such a collection? In other words, how much work would we have to perform in order to assemble

the charges, starting from an initial state in which they are all

at rest and very widely

separated?

located at displacement

located at displacement  is

written

is

written

to point

to point  is simply

where

is simply

where  is an element of the path taken between the two points. (See Section 1.3.2.)

The negative sign in the previous expression comes about because we would have to

exert a force

is an element of the path taken between the two points. (See Section 1.3.2.)

The negative sign in the previous expression comes about because we would have to

exert a force  on the charge, in order to counteract the force

exerted by the electric field. Recall, finally, that the scalar potential field

generated by a point charge

on the charge, in order to counteract the force

exerted by the electric field. Recall, finally, that the scalar potential field

generated by a point charge  located at position

located at position  is

[See Equation (2.21).]

is

[See Equation (2.21).]

. In order to bring the

second charge into position at displacement

. In order to bring the

second charge into position at displacement  ,

we have to do work against the electric field

generated by the first charge. According to Equations (2.67) and (2.68),

this work is given by

,

we have to do work against the electric field

generated by the first charge. According to Equations (2.67) and (2.68),

this work is given by

is simply the sum of the works done against the electric fields generated by

charges 1 and 2, taken in isolation:

is simply the sum of the works done against the electric fields generated by

charges 1 and 2, taken in isolation:

charges:

charges:

must be less than

must be less than  makes the previous summation

rather messy. If we were to sum without restriction (other than

makes the previous summation

rather messy. If we were to sum without restriction (other than  ) then

each pair of charges would be counted twice. It is convenient to do just

this, and then to divide the result by two. Thus, we obtain

This is the electric potential energy (i.e., the difference between the total energy

and the kinetic energy) of a collection of point electric charges. We can think of this quantity as the

work required to bring stationary charges from infinity and assemble them in the

required formation. Alternatively, it is the kinetic energy that would

be released if the collection were dissolved, and the charges returned to infinity.

But where is this potential energy stored? Let us investigate further.

) then

each pair of charges would be counted twice. It is convenient to do just

this, and then to divide the result by two. Thus, we obtain

This is the electric potential energy (i.e., the difference between the total energy

and the kinetic energy) of a collection of point electric charges. We can think of this quantity as the

work required to bring stationary charges from infinity and assemble them in the

required formation. Alternatively, it is the kinetic energy that would

be released if the collection were dissolved, and the charges returned to infinity.

But where is this potential energy stored? Let us investigate further.

th charge due to the other

charges in the distribution. [See Equation (2.20).]

th charge due to the other

charges in the distribution. [See Equation (2.20).]

[see Equation (2.18)], and where the volume integrals are over all space.

Let us try this scheme out. We know from Equation (2.54) that

[see Equation (2.18)], and where the volume integrals are over all space.

Let us try this scheme out. We know from Equation (2.54) that

, so we obtain

, so we obtain

![$\displaystyle W = \frac{\epsilon_0}{2} \left[\int \nabla\cdot ({\bf E}\,\phi)\,dV

+

\int E^2\,dV\right]$](img1258.png)

is some volume that encloses all of the charges, and

is some volume that encloses all of the charges, and  is its bounding

surface. Let us assume that

is its bounding

surface. Let us assume that  is a sphere, centered on the origin, and let

us take the limit in which the radius

is a sphere, centered on the origin, and let

us take the limit in which the radius  of this sphere goes to infinity.

We know that, in general, the electric field at large distances from a

bounded charge

distribution looks like the field of a point charge, and, therefore,

falls off like

of this sphere goes to infinity.

We know that, in general, the electric field at large distances from a

bounded charge

distribution looks like the field of a point charge, and, therefore,

falls off like  . Likewise, the potential falls off like

. Likewise, the potential falls off like  . (See Section 2.1.7.) However,

the surface area of the sphere increases like

. (See Section 2.1.7.) However,

the surface area of the sphere increases like  . Hence, it is clear that, in the

limit as

. Hence, it is clear that, in the

limit as

, the surface integral in Equation (2.82) falls off

like

, the surface integral in Equation (2.82) falls off

like  , and is consequently zero.

Thus, Equation (2.82) reduces to

where the volume integral is over all space. This is a very interesting

result. It tells us that the potential energy of a continuous charge

distribution is stored in the electric field generated by that distribution. Of course, we now have to assume that

an electric field possesses an energy density

Incidentally, the fact that an electric field possess an energy density demonstrates that it has a real physical existence, and

is not just an aid to the calculation of electrostatic forces.

, and is consequently zero.

Thus, Equation (2.82) reduces to

where the volume integral is over all space. This is a very interesting

result. It tells us that the potential energy of a continuous charge

distribution is stored in the electric field generated by that distribution. Of course, we now have to assume that

an electric field possesses an energy density

Incidentally, the fact that an electric field possess an energy density demonstrates that it has a real physical existence, and

is not just an aid to the calculation of electrostatic forces.

that is uniformly distributed within a sphere of

radius

that is uniformly distributed within a sphere of

radius  centered on the origin. Let us imagine building up this charge distribution

from a succession of thin spherical layers of infinitesimal thickness. At each

stage, we gather a small amount of charge

centered on the origin. Let us imagine building up this charge distribution

from a succession of thin spherical layers of infinitesimal thickness. At each

stage, we gather a small amount of charge  from infinity, and spread it

over the surface of the sphere in a thin

layer extending from

from infinity, and spread it

over the surface of the sphere in a thin

layer extending from  to

to  . We continue this process until the final radius of the

sphere is

. We continue this process until the final radius of the

sphere is  . If

. If  is the sphere's charge when it has attained radius

is the sphere's charge when it has attained radius

then the work done in bringing a charge

then the work done in bringing a charge  to its surface is

to its surface is

located at its geometric center

(

located at its geometric center

( ). (See Section 2.1.7.) If the constant charge density of the sphere is

). (See Section 2.1.7.) If the constant charge density of the sphere is

then

then

is

plainly

is

plainly

as

as

. Here,

. Here,  is a standard spherical polar coordinate. (See Section A.23.) Application of Gauss's law,

is a standard spherical polar coordinate. (See Section A.23.) Application of Gauss's law,

is a sphere of radius

is a sphere of radius  , centered on the origin, gives

for

, centered on the origin, gives

for  , and

for

, and

for  . Equations (2.83), (2.92), and (2.93) yield

. Equations (2.83), (2.92), and (2.93) yield

th charge with its

own electric field is specifically excluded, whereas it is included in Equation (2.77). Thus,

the potential energies

(2.74) and (2.83) are different because in the former we start from

ready-made point charges, whereas in the latter we build up the whole

charge distribution from scratch. Hence, if we were to work out the

potential energy of a point charge distribution using Equation (2.83) then

we would obtain the energy (2.74) plus the energy required to assemble the

point charges. What is the energy required to assemble a point electric charge?

In fact, it is infinite. To see this, let us suppose, for the sake of argument, that

our point charges actually consist of electric charge uniformly distributed in small

spheres of radius

th charge with its

own electric field is specifically excluded, whereas it is included in Equation (2.77). Thus,

the potential energies

(2.74) and (2.83) are different because in the former we start from

ready-made point charges, whereas in the latter we build up the whole

charge distribution from scratch. Hence, if we were to work out the

potential energy of a point charge distribution using Equation (2.83) then

we would obtain the energy (2.74) plus the energy required to assemble the

point charges. What is the energy required to assemble a point electric charge?

In fact, it is infinite. To see this, let us suppose, for the sake of argument, that

our point charges actually consist of electric charge uniformly distributed in small

spheres of radius  . According to Equation (2.90), the energy required to assemble the

. According to Equation (2.90), the energy required to assemble the

th point charge is

th point charge is

th charge.

Thus, we can write

th charge.

Thus, we can write

, and the

self-energy of each charge becomes infinite. Thus, the potential

energies predicted by Equations (2.74) and (2.83) differ by an infinite amount.

What does this all mean? We have to conclude that the idea of locating electrostatic

potential energy in the electric field runs into conceptual difficulties in the presence of point electric charges. One way out of this dilemma would be to

say that elementary electric charges, such as protons and electrons, are not point objects, but instead have finite spatial extents. Regrettably, although protons have finite spatial extents (of about

, and the

self-energy of each charge becomes infinite. Thus, the potential

energies predicted by Equations (2.74) and (2.83) differ by an infinite amount.

What does this all mean? We have to conclude that the idea of locating electrostatic

potential energy in the electric field runs into conceptual difficulties in the presence of point electric charges. One way out of this dilemma would be to

say that elementary electric charges, such as protons and electrons, are not point objects, but instead have finite spatial extents. Regrettably, although protons have finite spatial extents (of about

), electrons really do seem to be point objects.

), electrons really do seem to be point objects.