Next: Method of Images Up: Electrostatic Fields Previous: Ideal Conductors

volts per meter. This

phenomenon, which is known as breakdown, is associated with the formation

of sparks. The most well-known example of the breakdown of

air is during a lightning

strike. Thus, a good charge-storing device is one that holds a relatively large amount

of charge, but only generates relatively small external electric fields (so as to avoid breakdown). Such a device is called

a capacitor.

volts per meter. This

phenomenon, which is known as breakdown, is associated with the formation

of sparks. The most well-known example of the breakdown of

air is during a lightning

strike. Thus, a good charge-storing device is one that holds a relatively large amount

of charge, but only generates relatively small external electric fields (so as to avoid breakdown). Such a device is called

a capacitor.

Consider two thin, parallel, conducting

plates of cross-sectional area  that are separated by

a small distance

that are separated by

a small distance  (i.e.,

(i.e.,

). Suppose that each plate

carries an equal and opposite charge

). Suppose that each plate

carries an equal and opposite charge  (where

(where  ). We expect this charge to

spread evenly over the plates to give an effective sheet charge density

). We expect this charge to

spread evenly over the plates to give an effective sheet charge density

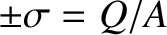

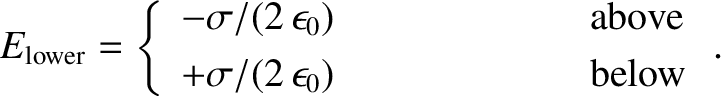

on each plate. Suppose that the upper plate carries a

positive charge and that the lower carries a negative charge. According to

Equation (2.130), the field generated by the upper plate is normal to the plate and

of magnitude

on each plate. Suppose that the upper plate carries a

positive charge and that the lower carries a negative charge. According to

Equation (2.130), the field generated by the upper plate is normal to the plate and

of magnitude

|

(2.136) |

|

(2.137) |

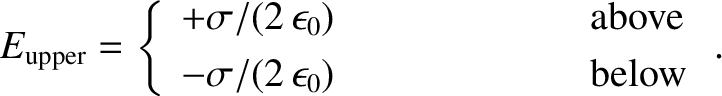

![\begin{displaymath}E_\perp =\left\{

\begin{array}{lcl}

\sigma /\epsilon_0&\mbox{...

...ex]

0& \mbox{\hspace{2cm}}&\mbox{otherwise}

\end{array}\right..\end{displaymath}](img1372.png) |

(2.138) |

|

(2.139) |

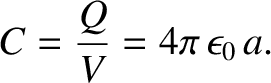

It is conventional to measure the capacity of a conductor, or set of conductors,

to store electric charge, but generate small external electric fields, in terms of a parameter

called capacitance. This parameter is

usually denoted  . The capacitance of a charge storing

device is simply the ratio of the charge stored to the potential difference

generated by this charge:

. The capacitance of a charge storing

device is simply the ratio of the charge stored to the potential difference

generated by this charge:

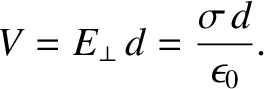

For a parallel plate capacitor, we have

Note that the capacitance only depends on geometric quantities, such as the area and spacing of the plates. This is a consequence of the superposability of electric fields. If we double the charge on a set of conductors then we double the electric fields generated around them, and we, therefore, double the potential difference between the conductors. Thus, the potential difference between the conductors is always directly proportional to the charge on the conductors. Moreover, the constant of proportionality (the inverse of the capacitance) can only depend on geometry.

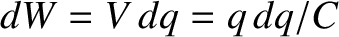

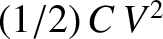

Suppose that the charge  on each plate of a parallel plate capacitor is built up gradually by transferring

small amounts of charge from one plate to another. If the

instantaneous charge on the plates is

on each plate of a parallel plate capacitor is built up gradually by transferring

small amounts of charge from one plate to another. If the

instantaneous charge on the plates is  , and an infinitesimal amount of

positive

charge

, and an infinitesimal amount of

positive

charge  is transferred from the negatively charged to the positively

charge plate, then the work done is

is transferred from the negatively charged to the positively

charge plate, then the work done is

,

where

,

where  is the instantaneous

voltage difference between the plates. (See Section 2.1.5.) Note that the voltage difference is such

that it opposes any increase in the charge on either plate.

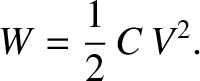

The total work done in charging the capacitor

is

is the instantaneous

voltage difference between the plates. (See Section 2.1.5.) Note that the voltage difference is such

that it opposes any increase in the charge on either plate.

The total work done in charging the capacitor

is

|

(2.143) |

The energy of

a charged parallel

plate

capacitor is actually stored in the electric field generated between the plates. This field

is of approximately constant magnitude

, and occupies a

region of volume

, and occupies a

region of volume  . Thus, given the energy density of an electric

field,

. Thus, given the energy density of an electric

field,

[see Equation (2.84)], the energy stored in the

electric field is

[see Equation (2.84)], the energy stored in the

electric field is

The idea, that we discussed in the previous section, that an electric field exerts a negative

pressure

on conductors immediately suggests that

the two plates in a parallel plate capacitor attract one another with a

mutual force

on conductors immediately suggests that

the two plates in a parallel plate capacitor attract one another with a

mutual force

It is not actually necessary to have two oppositely charged conductors

in order to make a capacitor.

Consider an isolated

conducting sphere of radius  , centered on the origin, that

carries an electric charge

, centered on the origin, that

carries an electric charge  . The spherically symmetric, radial electric field generated outside the sphere is

given by

. The spherically symmetric, radial electric field generated outside the sphere is

given by

|

(2.147) |

is a spherical polar coordinate. (See Section A.23.)

It follows that the potential difference between the sphere and infinity—or, more realistically,

some large, relatively distant reservoir of charge such as the Earth—is

Thus, the capacitance of the sphere is

is a spherical polar coordinate. (See Section A.23.)

It follows that the potential difference between the sphere and infinity—or, more realistically,

some large, relatively distant reservoir of charge such as the Earth—is

Thus, the capacitance of the sphere is

|

(2.149) |

is again given by

is again given by

. It can easily be demonstrated that this is equivalent to

the energy contained in the electric field surrounding the capacitor.

. It can easily be demonstrated that this is equivalent to

the energy contained in the electric field surrounding the capacitor.

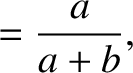

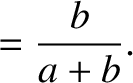

Suppose that we have two spheres of radii  and

and  , respectively, that are

connected by a long electric wire. See Figure 2.8. The wire allows electric charge to move back and forth between

the spheres until they reach the same potential (with respect to infinity).

Let

, respectively, that are

connected by a long electric wire. See Figure 2.8. The wire allows electric charge to move back and forth between

the spheres until they reach the same potential (with respect to infinity).

Let  be the charge on the first sphere, and

be the charge on the first sphere, and  the charge on the

second sphere.

Of course, the total charge

the charge on the

second sphere.

Of course, the total charge

carried by the two spheres is a conserved

quantity. It follows from Equation (2.148) that if the spheres are at the same potential then

carried by the two spheres is a conserved

quantity. It follows from Equation (2.148) that if the spheres are at the same potential then

|

|

(2.150) |

|

|

(2.151) |

—then

the large sphere grabs most of the charge; that is,

The ratio of the electric fields generated just above the surfaces of the two

spheres follows from Equations (2.146) and (2.152):

Note that if

—then

the large sphere grabs most of the charge; that is,

The ratio of the electric fields generated just above the surfaces of the two

spheres follows from Equations (2.146) and (2.152):

Note that if  then the field just above the smaller sphere

is far larger than that above the larger sphere.

Equation (2.153) is a simple example of a far more general rule; namely,

the electric field directly above some point on the

surface of a conductor is inversely proportional to

the local radius of curvature of the surface.

then the field just above the smaller sphere

is far larger than that above the larger sphere.

Equation (2.153) is a simple example of a far more general rule; namely,

the electric field directly above some point on the

surface of a conductor is inversely proportional to

the local radius of curvature of the surface.

It is clear that if we wish to store significant amounts of charge on a conductor then the surface of the conductor must be made as smooth as possible. Any sharp spikes on the surface will inevitably have comparatively small radii of curvature. Intense local electric fields are thus generated around such spikes. These fields can easily exceed the critical field for the breakdown of air, leading to sparking and the eventual loss of the charge on the conductor. Sparking can also be very destructive, because the associated electric currents flow through very localized regions, giving rise to intense ohmic heating.

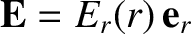

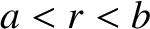

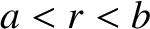

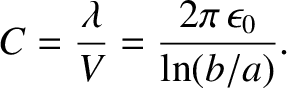

As a final example, consider two co-axial

conducting cylinders of radii  and

and

, where

, where  . Suppose that the charge per unit length carried by the

outer and inner cylinders is

. Suppose that the charge per unit length carried by the

outer and inner cylinders is  and

and  , respectively. We can safely

assume that

, respectively. We can safely

assume that

, by symmetry (adopting

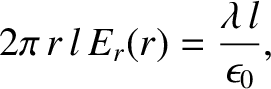

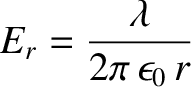

standard cylindrical polar coordinates). (See Section A.23.) Let us apply

Gauss's law (see Section 2.4) to a cylindrical surface of radius

, by symmetry (adopting

standard cylindrical polar coordinates). (See Section A.23.) Let us apply

Gauss's law (see Section 2.4) to a cylindrical surface of radius  , co-axial with the conductors, and

of length

, co-axial with the conductors, and

of length  . For

. For  , we find that

, we find that

|

(2.154) |

|

(2.155) |

. It is fairly obvious that

. It is fairly obvious that  if

if  is not in the range

is not in the range

to

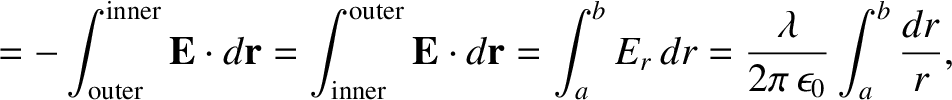

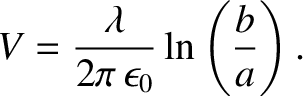

to  . The potential difference between the inner and outer cylinders is [see Equation (2.17)]

. The potential difference between the inner and outer cylinders is [see Equation (2.17)]

|

|

(2.156) |

|

(2.157) |

|

(2.158) |