Consider a gas of uniform number density,  , that has a gradient in the

, that has a gradient in the  -component of its mean flow velocity,

-component of its mean flow velocity,  , along the

, along the  -axis, such that

-axis, such that

|

(5.261) |

It is assumed that the mean flow velocity is much less than the mean molecular speed.

Slightly modifying the analysis of the previous

two sections, the  -momentum per unit area, per second, carried by molecules whose speeds lie between

-momentum per unit area, per second, carried by molecules whose speeds lie between

and

and  , and whose directions of motion subtend an angle lying between

, and whose directions of motion subtend an angle lying between  and

and

with the

with the  -axis, that cross the

-axis, that cross the  -

- plane, is

plane, is

![$\displaystyle dP_{xz}= \left[m\,V_x'\right]\left[n\,F(v)\,dv\right]\left[\frac{1}{2}\,\sin\theta\,d\theta\right][v\,\cos\theta],$](img3846.png) |

(5.262) |

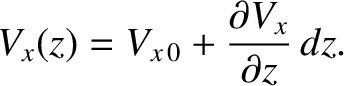

where  is the distribution of molecular speeds,

is the distribution of molecular speeds,  the molecular mass, and

the molecular mass, and  the

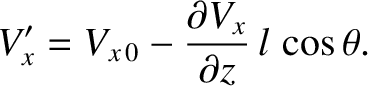

the  -component of flow velocity where the molecules last

made a collision.

On average, the

molecules move a distance

-component of flow velocity where the molecules last

made a collision.

On average, the

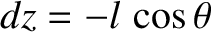

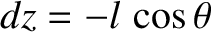

molecules move a distance  (i.e., the mean free path) between collisions. Hence,

(i.e., the mean free path) between collisions. Hence,

,

and

,

and

|

(5.263) |

Thus, the net flux of  -momentum across the

-momentum across the  -

- plane is

plane is

![$\displaystyle P_{xz} =\frac{m\,n}{2}\int_0^\pi\left[V_{x\,0}-\frac{\partial V_x...

...z}\,l\,\cos\theta\right]\cos\theta\,\sin\theta\,d\theta \int_0^\infty F(v)\,dv,$](img3849.png) |

(5.264) |

which gives

|

(5.265) |

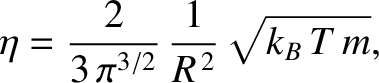

where

|

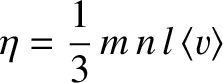

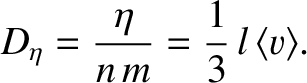

(5.266) |

is termed the viscosity. Here,

is the mean molecular speed. (See Section 5.5.9.)

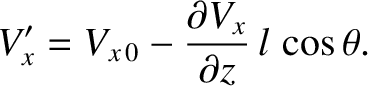

Thus, we conclude that the flux of

is the mean molecular speed. (See Section 5.5.9.)

Thus, we conclude that the flux of  -momentum in the

-momentum in the  -direction is proportional to minus the

gradient of the

-direction is proportional to minus the

gradient of the  -component of the flow velocity with respect to

-component of the flow velocity with respect to  . This is yet another example of Fick's law.

. This is yet another example of Fick's law.

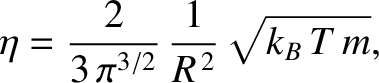

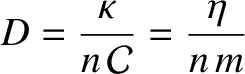

Equations (5.219), (5.244), and (5.266) imply that

yield

|

(5.267) |

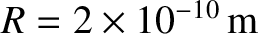

where  is the molecular diameter, and

is the molecular diameter, and  the gas temperature.

It can be seen that the viscosity of an ideal gas scales as

the gas temperature.

It can be seen that the viscosity of an ideal gas scales as  , and

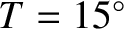

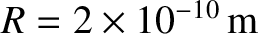

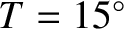

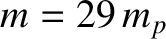

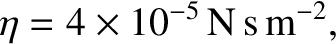

is independent of the pressure at constant temperature. The previous formula yields the following estimate for the viscosity of air (assuming that

, and

is independent of the pressure at constant temperature. The previous formula yields the following estimate for the viscosity of air (assuming that

C,

C,

, and

, and  ),

),

|

(5.268) |

which turns out to be too large by a factor 2 (because of the approximate nature of our calculation).

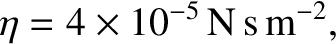

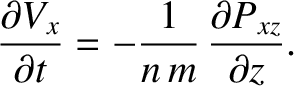

Consider a slab of gas lying between  and

and  . The rate of change of the

. The rate of change of the  -momentum contained in the slab is the difference between the flux of momentum into the slab and the flux of

momentum out of the slab. In other words,

-momentum contained in the slab is the difference between the flux of momentum into the slab and the flux of

momentum out of the slab. In other words,

![$\displaystyle \frac{\partial (n\,A\,dz\,m\,V_x)}{\partial t} = \left[P_{xz}(z,t)- P_{xz}(z+dz,t)\right]A,$](img3854.png) |

(5.269) |

where  is the cross-sectional area of the slab. It follows that

is the cross-sectional area of the slab. It follows that

|

(5.270) |

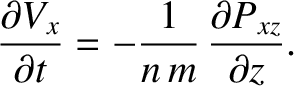

Making use of Equations (5.265) and (5.266), we get

|

(5.271) |

where

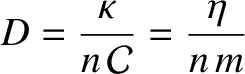

|

(5.272) |

Of course, Equation (5.271) is the diffusion equation, and  is the associated diffusivity.

Thus, we conclude, by comparison with the analysis in the previous two sections, that momentum diffuses through

an ideal gas at the same very slow rate at which molecules and heat diffuse. Moreover, it is clear, from Sections 5.1.5 and 5.1.7, that momentum diffusion is due to a

random walk of molecules with excess momentum under the action of molecular collisions.

is the associated diffusivity.

Thus, we conclude, by comparison with the analysis in the previous two sections, that momentum diffuses through

an ideal gas at the same very slow rate at which molecules and heat diffuse. Moreover, it is clear, from Sections 5.1.5 and 5.1.7, that momentum diffusion is due to a

random walk of molecules with excess momentum under the action of molecular collisions.

Equations (5.235), (5.260), and (5.272) lead to the prediction that

|

(5.273) |

for an ideal gas, where  is the molecular diffusivity,

is the molecular diffusivity,  the thermal conductivity,

the thermal conductivity,  the viscosity,

the viscosity,  the number density of molecules,

the number density of molecules,  the molecular mass, and

the molecular mass, and  the molecular heat capacity. It turns out that this prediction is only approximately true

due to additional factors, such as intermolecular forces, that have not been incorporated into our highly simplified analysis. For example, the ratio

the molecular heat capacity. It turns out that this prediction is only approximately true

due to additional factors, such as intermolecular forces, that have not been incorporated into our highly simplified analysis. For example, the ratio

, which should be unity according to simple

kinetic theory, actually takes the values

, which should be unity according to simple

kinetic theory, actually takes the values  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  for helium, argon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and

oxygen, respectively, at standard temperature and pressure.

for helium, argon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and

oxygen, respectively, at standard temperature and pressure.

The prediction that the thermal conductivity and viscosity of an ideal gas are both independent of the

gas pressure, at constant temperature, breaks down when the pressure becomes sufficiently low that the

mean free path between collisions becomes comparable with the size of the gas's container. Under these circumstances, the

thermal conductivity and viscosity both become approximately proportional to the pressure, at constant temperature.

, that has a gradient in the

, that has a gradient in the  -component of its mean flow velocity,

-component of its mean flow velocity,  , along the

, along the  -axis, such that

-axis, such that

-momentum per unit area, per second, carried by molecules whose speeds lie between

-momentum per unit area, per second, carried by molecules whose speeds lie between

and

and  , and whose directions of motion subtend an angle lying between

, and whose directions of motion subtend an angle lying between  and

and

with the

with the  -axis, that cross the

-axis, that cross the  -

- plane, is

plane, is

![$\displaystyle dP_{xz}= \left[m\,V_x'\right]\left[n\,F(v)\,dv\right]\left[\frac{1}{2}\,\sin\theta\,d\theta\right][v\,\cos\theta],$](img3846.png)

is the distribution of molecular speeds,

is the distribution of molecular speeds,  the molecular mass, and

the molecular mass, and  the

the  -component of flow velocity where the molecules last

made a collision.

On average, the

molecules move a distance

-component of flow velocity where the molecules last

made a collision.

On average, the

molecules move a distance  (i.e., the mean free path) between collisions. Hence,

(i.e., the mean free path) between collisions. Hence,

,

and

,

and

-momentum across the

-momentum across the  -

- plane is

plane is

![$\displaystyle P_{xz} =\frac{m\,n}{2}\int_0^\pi\left[V_{x\,0}-\frac{\partial V_x...

...z}\,l\,\cos\theta\right]\cos\theta\,\sin\theta\,d\theta \int_0^\infty F(v)\,dv,$](img3849.png)

is the mean molecular speed. (See Section 5.5.9.)

Thus, we conclude that the flux of

is the mean molecular speed. (See Section 5.5.9.)

Thus, we conclude that the flux of  -momentum in the

-momentum in the  -direction is proportional to minus the

gradient of the

-direction is proportional to minus the

gradient of the  -component of the flow velocity with respect to

-component of the flow velocity with respect to  . This is yet another example of Fick's law.

. This is yet another example of Fick's law.

is the molecular diameter, and

is the molecular diameter, and  the gas temperature.

It can be seen that the viscosity of an ideal gas scales as

the gas temperature.

It can be seen that the viscosity of an ideal gas scales as  , and

is independent of the pressure at constant temperature. The previous formula yields the following estimate for the viscosity of air (assuming that

, and

is independent of the pressure at constant temperature. The previous formula yields the following estimate for the viscosity of air (assuming that

C,

C,

, and

, and  ),

),

and

and  . The rate of change of the

. The rate of change of the  -momentum contained in the slab is the difference between the flux of momentum into the slab and the flux of

momentum out of the slab. In other words,

-momentum contained in the slab is the difference between the flux of momentum into the slab and the flux of

momentum out of the slab. In other words,

![$\displaystyle \frac{\partial (n\,A\,dz\,m\,V_x)}{\partial t} = \left[P_{xz}(z,t)- P_{xz}(z+dz,t)\right]A,$](img3854.png)

is the cross-sectional area of the slab. It follows that

is the cross-sectional area of the slab. It follows that

is the associated diffusivity.

Thus, we conclude, by comparison with the analysis in the previous two sections, that momentum diffuses through

an ideal gas at the same very slow rate at which molecules and heat diffuse. Moreover, it is clear, from Sections 5.1.5 and 5.1.7, that momentum diffusion is due to a

random walk of molecules with excess momentum under the action of molecular collisions.

is the associated diffusivity.

Thus, we conclude, by comparison with the analysis in the previous two sections, that momentum diffuses through

an ideal gas at the same very slow rate at which molecules and heat diffuse. Moreover, it is clear, from Sections 5.1.5 and 5.1.7, that momentum diffusion is due to a

random walk of molecules with excess momentum under the action of molecular collisions.

is the molecular diffusivity,

is the molecular diffusivity,  the thermal conductivity,

the thermal conductivity,  the viscosity,

the viscosity,  the number density of molecules,

the number density of molecules,  the molecular mass, and

the molecular mass, and  the molecular heat capacity. It turns out that this prediction is only approximately true

due to additional factors, such as intermolecular forces, that have not been incorporated into our highly simplified analysis. For example, the ratio

the molecular heat capacity. It turns out that this prediction is only approximately true

due to additional factors, such as intermolecular forces, that have not been incorporated into our highly simplified analysis. For example, the ratio

, which should be unity according to simple

kinetic theory, actually takes the values

, which should be unity according to simple

kinetic theory, actually takes the values  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  for helium, argon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and

oxygen, respectively, at standard temperature and pressure.

for helium, argon, hydrogen, nitrogen, and

oxygen, respectively, at standard temperature and pressure.