Specific Heats of Solids

Consider a simple solid containing  atoms. Now, atoms in solids cannot

translate (unlike those in gases), but

are free to vibrate about their equilibrium positions.

Such vibrations are termed lattice vibrations, and can be thought of

as sound waves propagating

through the crystal lattice. Each atom is specified by three independent position

coordinates, and three corresponding momentum coordinates. Let us

only consider small-amplitude vibrations.

In this case, we can expand the potential energy of interaction between the atoms

to give an expression that is quadratic in the atomic displacements

from their equilibrium positions. It is always possible to perform a

normal mode analysis

of the oscillations. In effect, we can find

atoms. Now, atoms in solids cannot

translate (unlike those in gases), but

are free to vibrate about their equilibrium positions.

Such vibrations are termed lattice vibrations, and can be thought of

as sound waves propagating

through the crystal lattice. Each atom is specified by three independent position

coordinates, and three corresponding momentum coordinates. Let us

only consider small-amplitude vibrations.

In this case, we can expand the potential energy of interaction between the atoms

to give an expression that is quadratic in the atomic displacements

from their equilibrium positions. It is always possible to perform a

normal mode analysis

of the oscillations. In effect, we can find  independent modes of oscillation of the solid.

Each mode has its own particular oscillation frequency, and its own particular pattern

of atomic displacements.

Any general oscillation can be written as a linear combination of these

normal modes.

Let

independent modes of oscillation of the solid.

Each mode has its own particular oscillation frequency, and its own particular pattern

of atomic displacements.

Any general oscillation can be written as a linear combination of these

normal modes.

Let  be the (appropriately normalized) amplitude of the

be the (appropriately normalized) amplitude of the  th normal mode,

and

th normal mode,

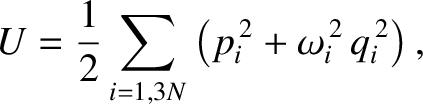

and  the corresponding momentum. In normal-mode coordinates, the internal energy of the lattice vibrations takes the

particularly simple form

the corresponding momentum. In normal-mode coordinates, the internal energy of the lattice vibrations takes the

particularly simple form

|

(5.487) |

where  is the (angular) oscillation frequency of the

is the (angular) oscillation frequency of the  th normal mode. It is

clear that, when expressed in normal-mode coordinates, the linearized lattice vibrations are equivalent to

th normal mode. It is

clear that, when expressed in normal-mode coordinates, the linearized lattice vibrations are equivalent to

independent harmonic oscillators. (Of course, each oscillator corresponds to a different normal

mode.)

independent harmonic oscillators. (Of course, each oscillator corresponds to a different normal

mode.)

The typical value of  is the (angular) frequency of a sound wave

propagating through the lattice. Sound wave frequencies are far lower than the

typical vibration frequencies of gaseous molecules. In the latter case, the mass involved in the

vibration is simply that of the molecule, whereas in the former case the mass involved is that

of very many atoms (because lattice vibrations are non-localized). The strength of

interatomic bonds in gaseous molecules is similar to those in solids, so we can use the estimate

is the (angular) frequency of a sound wave

propagating through the lattice. Sound wave frequencies are far lower than the

typical vibration frequencies of gaseous molecules. In the latter case, the mass involved in the

vibration is simply that of the molecule, whereas in the former case the mass involved is that

of very many atoms (because lattice vibrations are non-localized). The strength of

interatomic bonds in gaseous molecules is similar to those in solids, so we can use the estimate

(

( is the force constant that measures the strength of

interatomic bonds, and

is the force constant that measures the strength of

interatomic bonds, and  is the mass involved in the oscillation) as proof that the typical

frequencies of lattice vibrations are very

much less than the vibration frequencies of simple molecules.

It follows, from

is the mass involved in the oscillation) as proof that the typical

frequencies of lattice vibrations are very

much less than the vibration frequencies of simple molecules.

It follows, from

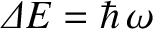

, that the quantum energy levels of lattice vibrations are

far more closely spaced than the vibrational energy levels of gaseous molecules. Thus, it is

likely (and is, indeed, the case) that lattice vibrations are not frozen out at room temperature,

but, instead, make their full classical contribution to the molar specific heat of the solid. (See Section 5.5.8.)

, that the quantum energy levels of lattice vibrations are

far more closely spaced than the vibrational energy levels of gaseous molecules. Thus, it is

likely (and is, indeed, the case) that lattice vibrations are not frozen out at room temperature,

but, instead, make their full classical contribution to the molar specific heat of the solid. (See Section 5.5.8.)

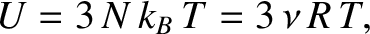

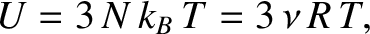

If the lattice vibrations behave classically then, according to the equipartition theorem (see Section 5.5.5),

each normal mode of oscillation has an associated mean energy  , in equilibrium at

temperature

, in equilibrium at

temperature  [

[

resides in the kinetic energy of the oscillation,

and

resides in the kinetic energy of the oscillation,

and

resides in the potential energy].

Thus, the internal energy of the solid is

resides in the potential energy].

Thus, the internal energy of the solid is

|

(5.488) |

where

.

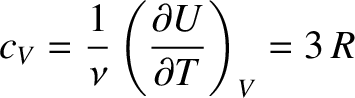

It follows that the molar heat capacity at constant volume is

.

It follows that the molar heat capacity at constant volume is

|

(5.489) |

for solids. This gives a value of  joules/mole/degree. In fact, at room temperature, most

solids (in particular, metals)

have heat capacities that lie remarkably close to this value. This

fact was discovered

experimentally by Pierre Dulong and Alexis Petite at the beginning of the nineteenth century, and was used to

make some of the first

crude estimates of the molecular weights of solids. (If we know the molar heat capacity

of a substance

then we can easily work out how much of it corresponds to one mole, and

by weighing this amount, and then dividing the result by Avogadro's number,

we can then obtain an estimate of the molecular weight.)

joules/mole/degree. In fact, at room temperature, most

solids (in particular, metals)

have heat capacities that lie remarkably close to this value. This

fact was discovered

experimentally by Pierre Dulong and Alexis Petite at the beginning of the nineteenth century, and was used to

make some of the first

crude estimates of the molecular weights of solids. (If we know the molar heat capacity

of a substance

then we can easily work out how much of it corresponds to one mole, and

by weighing this amount, and then dividing the result by Avogadro's number,

we can then obtain an estimate of the molecular weight.)

Table 5.3 lists the experimental

molar heat

capacities,  , at constant pressure for various solids. The heat capacity at constant

volume is somewhat less than the constant pressure value, but not by much,

because solids

are fairly incompressible.

It can be seen that Dulong and Petite's law (i.e., that all solids have a molar heat capacities

close to

, at constant pressure for various solids. The heat capacity at constant

volume is somewhat less than the constant pressure value, but not by much,

because solids

are fairly incompressible.

It can be seen that Dulong and Petite's law (i.e., that all solids have a molar heat capacities

close to  joules/mole/degree) holds fairly well for metals.

However, the law fails badly for

diamond. This is not surprising. As is well known,

diamond is an extremely hard substance, so its interatomic bonds must be very strong, suggesting

that the force constant,

joules/mole/degree) holds fairly well for metals.

However, the law fails badly for

diamond. This is not surprising. As is well known,

diamond is an extremely hard substance, so its interatomic bonds must be very strong, suggesting

that the force constant,  , is large.

Diamond is also a fairly low-density substance, so the mass,

, is large.

Diamond is also a fairly low-density substance, so the mass,  , involved in

lattice vibrations is comparatively small. Both these facts suggest that the typical lattice vibration

frequency of diamond (

, involved in

lattice vibrations is comparatively small. Both these facts suggest that the typical lattice vibration

frequency of diamond (

) is high. In fact, the spacing between

the different vibrational energy

levels (which scales like

) is high. In fact, the spacing between

the different vibrational energy

levels (which scales like

) is sufficiently large in diamond for the vibrational

degrees of freedom

to be largely frozen out at room temperature. This accounts for the anomalously low

heat capacity of diamond in Table 5.3.

) is sufficiently large in diamond for the vibrational

degrees of freedom

to be largely frozen out at room temperature. This accounts for the anomalously low

heat capacity of diamond in Table 5.3.

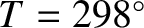

Table: 5.3

Values of  (joules/mole/degree) for some solids at

(joules/mole/degree) for some solids at

K.

K.

| |

|

|

|

| Solid |

|

Solid |

|

| Copper |

24.5 |

Aluminium |

24.4 |

| Silver |

25.5 |

Tin (white) |

26.4 |

| Lead |

26.4 |

Sulphur (rhombic) |

22.4 |

| Zinc |

25.4 |

Carbon (diamond) |

6.1 |

|

Dulong and Petite's law is essentially a high-temperature limit. We can make

a crude model of the behavior of  at low temperatures by assuming that all of the normal

modes oscillate at the same frequency,

at low temperatures by assuming that all of the normal

modes oscillate at the same frequency,  (say). This approximation was first employed by

Einstein in a paper published in 1907. According to Equation (5.487),

the solid acts like a set

of

(say). This approximation was first employed by

Einstein in a paper published in 1907. According to Equation (5.487),

the solid acts like a set

of  independent oscillators which, making use of

Einstein's approximation, all vibrate at the same frequency.

We can use the quantum mechanical result (5.390) for the mean energy of a single

oscillator to write the internal energy

of the solid in the form

independent oscillators which, making use of

Einstein's approximation, all vibrate at the same frequency.

We can use the quantum mechanical result (5.390) for the mean energy of a single

oscillator to write the internal energy

of the solid in the form

![$\displaystyle U = 3\,N \left[\frac{1}{2} +

\frac{1}{\exp(\hbar\,\omega/k_B\,T) - 1} \right]\hbar\,\omega,$](img4387.png) |

(5.490) |

giving

![$\displaystyle c_V \frac{1}{\nu}\left(\frac{\partial U}{\partial T}\right)_V= 3\...

...c{\theta_E}{T}\right)^2 \frac{\exp(\theta_E / T)}

{[\exp(\theta_E/T) - 1]^{2}}.$](img4388.png) |

(5.491) |

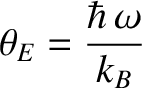

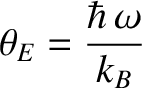

Here,

|

(5.492) |

is termed the Einstein temperature. If the temperature is sufficiently

high that

then the previous expression reduces to

then the previous expression reduces to

, after expansion of the exponential functions. Thus, the law of Dulong and

Petite is recovered for temperatures significantly in excess of the Einstein temperature.

On the other hand, if the temperature is sufficiently

low that

, after expansion of the exponential functions. Thus, the law of Dulong and

Petite is recovered for temperatures significantly in excess of the Einstein temperature.

On the other hand, if the temperature is sufficiently

low that

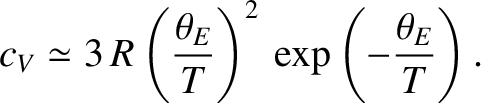

then the

exponential factors appearing in Equation (5.491) become very much larger than unity, giving

then the

exponential factors appearing in Equation (5.491) become very much larger than unity, giving

|

(5.493) |

So, in this simple model, the specific heat approaches zero exponentially as

.

.

In reality, the specific heats of solids do not approach zero quite as quickly as

suggested by Einstein's model when

. The experimentally observed low-temperature

behavior is more like

. The experimentally observed low-temperature

behavior is more like

. The reason for this discrepancy is the crude

approximation

that all normal modes have the same frequency. In fact, long-wavelength modes have lower frequencies

than short-wavelength modes, so the former are much harder to freeze out than the latter

(because the spacing between quantum energy levels,

. The reason for this discrepancy is the crude

approximation

that all normal modes have the same frequency. In fact, long-wavelength modes have lower frequencies

than short-wavelength modes, so the former are much harder to freeze out than the latter

(because the spacing between quantum energy levels,

, is smaller in the former case).

The molar

heat capacity does not decrease with temperature as rapidly as suggested by Einstein's model

because these long-wavelength modes are able to make a significant contribution

to the heat capacity, even at very low

temperatures. A more realistic model of lattice vibrations was developed by

Peter Debye in 1912.

In the Debye model, the frequencies of the normal modes of vibration are estimated by treating

the solid as an isotropic continuous medium. This approach is reasonable because the only modes

that really matter at low temperatures are the long-wavelength modes; more explicitly, those whose

wavelengths greatly exceed the interatomic spacing. It is plausible that these modes are not

particularly

sensitive to the discrete nature of the solid. In other words, they are not sensitive to the fact that the solid is made up of atoms,

rather than being continuous.

, is smaller in the former case).

The molar

heat capacity does not decrease with temperature as rapidly as suggested by Einstein's model

because these long-wavelength modes are able to make a significant contribution

to the heat capacity, even at very low

temperatures. A more realistic model of lattice vibrations was developed by

Peter Debye in 1912.

In the Debye model, the frequencies of the normal modes of vibration are estimated by treating

the solid as an isotropic continuous medium. This approach is reasonable because the only modes

that really matter at low temperatures are the long-wavelength modes; more explicitly, those whose

wavelengths greatly exceed the interatomic spacing. It is plausible that these modes are not

particularly

sensitive to the discrete nature of the solid. In other words, they are not sensitive to the fact that the solid is made up of atoms,

rather than being continuous.

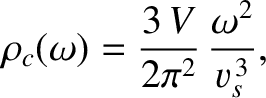

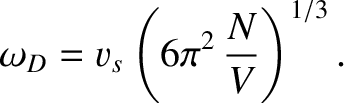

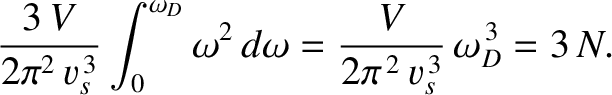

According to Equation (5.461), the density of sound wave states in a continuous solid is

|

(5.494) |

where  is the average sound speed.

The Debye approach consists in approximating the actual density of sound wave states,

is the average sound speed.

The Debye approach consists in approximating the actual density of sound wave states,

, by the density in a continuous medium,

, by the density in a continuous medium,

, not

only at low frequencies (long wavelengths) where these should be nearly the same, but

also at high frequencies where they may differ substantially. Suppose that we are

dealing with a solid consisting of

, not

only at low frequencies (long wavelengths) where these should be nearly the same, but

also at high frequencies where they may differ substantially. Suppose that we are

dealing with a solid consisting of  atoms. We know that there are

only

atoms. We know that there are

only  independent normal modes. It follows that we must cut off the

density of states above some critical frequency,

independent normal modes. It follows that we must cut off the

density of states above some critical frequency,  (say), otherwise we

will have too many modes. Thus, in the Debye approximation, the density

of normal modes takes the form

(say), otherwise we

will have too many modes. Thus, in the Debye approximation, the density

of normal modes takes the form

![\begin{displaymath}\rho_D(\omega) = \left\{

\begin{array}{lll}\rho_c(\omega) &\m...

...eq \omega_D\\ [0.5ex]

0& & \omega>\omega_D

\end{array}\right. .\end{displaymath}](img4400.png) |

(5.495) |

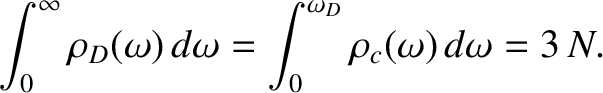

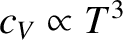

Here,  is termed the Debye frequency, and is chosen such that

the total number of normal modes is

is termed the Debye frequency, and is chosen such that

the total number of normal modes is  :

:

|

(5.496) |

Substituting Equation (5.494) into the previous formula yields

|

(5.497) |

This implies that

|

(5.498) |

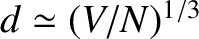

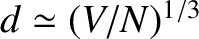

Thus, the Debye frequency depends only on the sound speed in the solid, and the number

of atoms per unit volume. The wavelength corresponding to the Debye frequency

is

, which is clearly on the order of the interatomic spacing,

, which is clearly on the order of the interatomic spacing,

.

It follows that the cut-off of normal modes whose frequencies exceed the Debye frequency

is equivalent to a cut-off of normal modes whose wavelengths are less than the interatomic

spacing. Of course, it makes physical sense that such modes should be absent.

.

It follows that the cut-off of normal modes whose frequencies exceed the Debye frequency

is equivalent to a cut-off of normal modes whose wavelengths are less than the interatomic

spacing. Of course, it makes physical sense that such modes should be absent.

We can use the quantum-mechanical expression for the

mean energy of a single oscillator, Equation (5.390), to calculate the internal energy associated with lattice vibrations in the Debye approximation. We obtain

![$\displaystyle U = \int_0^\infty \rho_D(\omega)

\left[\frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{\exp(\hbar\, \omega/k_B\,T)-1}\right]\hbar\,\omega\,d\omega.$](img4406.png) |

(5.499) |

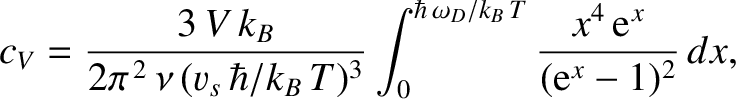

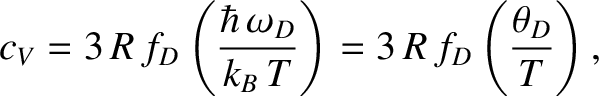

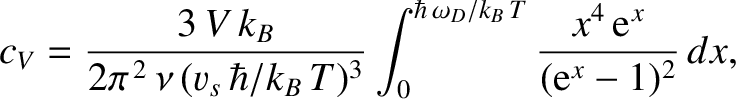

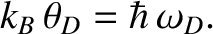

Hence, the molar heat capacity takes the form

![$\displaystyle c_V =\frac{1}{\nu}\left(\frac{\partial U}{\partial T}\right)_V

= ...

...,\omega}

{[\exp(\hbar\,\omega/k_B\,T)-1]^{\,2}}\right\}

\hbar\,\omega\,d\omega.$](img4407.png) |

(5.500) |

Making use of Equations (5.494) and (5.495), we find that

![$\displaystyle c_V = \frac{k_B}{\nu}\int_0^{\omega_D} \frac{\exp(\hbar\,\omega/k...

...\omega/k_B\,T)-1]^{2}}\,

\frac{3 \,V}{2\pi^2 \,v_s^{\,3}}\,\omega^{2}\,d\omega,$](img4408.png) |

(5.501) |

giving

|

(5.502) |

in terms of the dimensionless variable

.

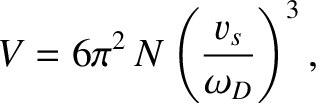

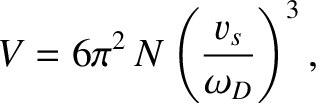

According to Equation (5.498), the volume can be written

.

According to Equation (5.498), the volume can be written

|

(5.503) |

so the heat capacity reduces to

|

(5.504) |

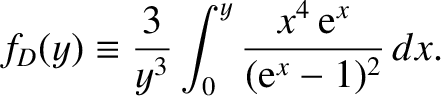

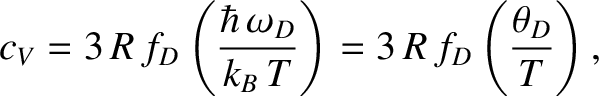

where the Debye function is defined

|

(5.505) |

We have also defined the Debye temperature,  , as

, as

|

(5.506) |

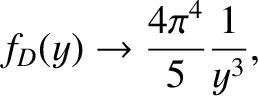

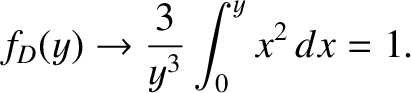

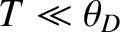

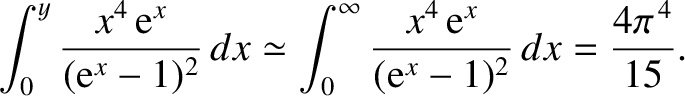

Consider the asymptotic limit in which

. For small

. For small  , we can approximate

, we can approximate

as

as  in the integrand of Equation (5.505), so that

in the integrand of Equation (5.505), so that

|

(5.507) |

Thus, if the temperature greatly exceeds the Debye temperature then we recover the law of

Dulong and Petite that

. Consider, now, the

asymptotic limit in which

. Consider, now, the

asymptotic limit in which

. For large

. For large  ,

,

|

(5.508) |

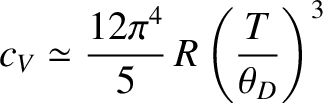

The latter integral can be looked up in standard reference books on integrals. Thus, in the low-temperature limit,

|

(5.509) |

which yields

|

(5.510) |

in the limit

, Note that

, Note that  varies with temperature as

varies with temperature as  , in accordance with experimental

observation.

, in accordance with experimental

observation.

Table 5.4:

Comparison of Debye temperatures (in degrees kelvin) obtained from the

low temperature behavior of the heat capacity with those calculated from the

sound speed.

| Solid |

(low temperature) (low temperature) |

(sound speed) (sound speed) |

| Na Cl |

308 |

320 |

| K Cl |

230 |

246 |

| Ag |

225 |

216 |

| Zn |

308 |

305 |

|

The fact that  goes like

goes like  at low temperatures is quite well verified experimentally,

although it is sometimes necessary to go to temperatures as low as

at low temperatures is quite well verified experimentally,

although it is sometimes necessary to go to temperatures as low as

to obtain

this asymptotic behavior. Theoretically,

to obtain

this asymptotic behavior. Theoretically,  should be calculable from

Equation (5.498)

in terms of the sound speed in the solid, and the molar volume. Table 5.4 shows a

comparison of Debye temperatures evaluated by this means with temperatures obtained

empirically by fitting the law (5.510) to the low-temperature variation of the

heat capacity. It can be seen that there is fairly good agreement between the theoretical and

empirical Debye temperatures. This suggests that the Debye theory affords a good, though not

perfect, representation of the behavior of

should be calculable from

Equation (5.498)

in terms of the sound speed in the solid, and the molar volume. Table 5.4 shows a

comparison of Debye temperatures evaluated by this means with temperatures obtained

empirically by fitting the law (5.510) to the low-temperature variation of the

heat capacity. It can be seen that there is fairly good agreement between the theoretical and

empirical Debye temperatures. This suggests that the Debye theory affords a good, though not

perfect, representation of the behavior of  in solids over the entire temperature range.

in solids over the entire temperature range.

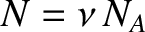

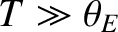

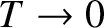

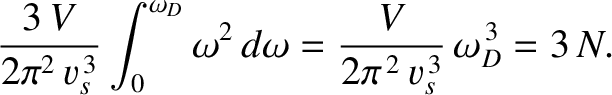

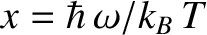

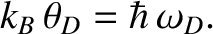

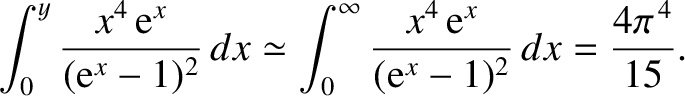

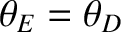

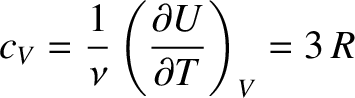

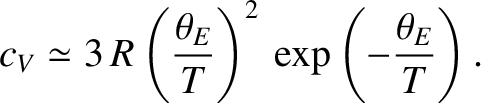

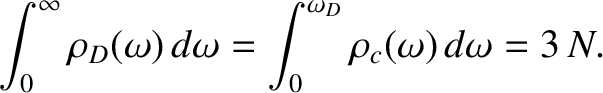

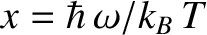

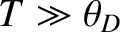

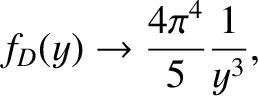

Figure: 5.9

The molar heat capacity of various solids. The solid

curve shows the prediction of Debye theory. The dotted curve shows the prediction of Einstein theory (assuming that

).

).

|

|

Finally, Figure 5.9 shows the actual temperature variation of the molar heat capacities

of various solids, as well as that predicted by Debye's theory. The prediction of Einstein's theory

is also shown, for the sake of comparison.

atoms. Now, atoms in solids cannot

translate (unlike those in gases), but

are free to vibrate about their equilibrium positions.

Such vibrations are termed lattice vibrations, and can be thought of

as sound waves propagating

through the crystal lattice. Each atom is specified by three independent position

coordinates, and three corresponding momentum coordinates. Let us

only consider small-amplitude vibrations.

In this case, we can expand the potential energy of interaction between the atoms

to give an expression that is quadratic in the atomic displacements

from their equilibrium positions. It is always possible to perform a

normal mode analysis

of the oscillations. In effect, we can find

atoms. Now, atoms in solids cannot

translate (unlike those in gases), but

are free to vibrate about their equilibrium positions.

Such vibrations are termed lattice vibrations, and can be thought of

as sound waves propagating

through the crystal lattice. Each atom is specified by three independent position

coordinates, and three corresponding momentum coordinates. Let us

only consider small-amplitude vibrations.

In this case, we can expand the potential energy of interaction between the atoms

to give an expression that is quadratic in the atomic displacements

from their equilibrium positions. It is always possible to perform a

normal mode analysis

of the oscillations. In effect, we can find  independent modes of oscillation of the solid.

Each mode has its own particular oscillation frequency, and its own particular pattern

of atomic displacements.

Any general oscillation can be written as a linear combination of these

normal modes.

Let

independent modes of oscillation of the solid.

Each mode has its own particular oscillation frequency, and its own particular pattern

of atomic displacements.

Any general oscillation can be written as a linear combination of these

normal modes.

Let  be the (appropriately normalized) amplitude of the

be the (appropriately normalized) amplitude of the  th normal mode,

and

th normal mode,

and  the corresponding momentum. In normal-mode coordinates, the internal energy of the lattice vibrations takes the

particularly simple form

where

the corresponding momentum. In normal-mode coordinates, the internal energy of the lattice vibrations takes the

particularly simple form

where  is the (angular) oscillation frequency of the

is the (angular) oscillation frequency of the  th normal mode. It is

clear that, when expressed in normal-mode coordinates, the linearized lattice vibrations are equivalent to

th normal mode. It is

clear that, when expressed in normal-mode coordinates, the linearized lattice vibrations are equivalent to

independent harmonic oscillators. (Of course, each oscillator corresponds to a different normal

mode.)

independent harmonic oscillators. (Of course, each oscillator corresponds to a different normal

mode.)

is the (angular) frequency of a sound wave

propagating through the lattice. Sound wave frequencies are far lower than the

typical vibration frequencies of gaseous molecules. In the latter case, the mass involved in the

vibration is simply that of the molecule, whereas in the former case the mass involved is that

of very many atoms (because lattice vibrations are non-localized). The strength of

interatomic bonds in gaseous molecules is similar to those in solids, so we can use the estimate

is the (angular) frequency of a sound wave

propagating through the lattice. Sound wave frequencies are far lower than the

typical vibration frequencies of gaseous molecules. In the latter case, the mass involved in the

vibration is simply that of the molecule, whereas in the former case the mass involved is that

of very many atoms (because lattice vibrations are non-localized). The strength of

interatomic bonds in gaseous molecules is similar to those in solids, so we can use the estimate

(

( is the force constant that measures the strength of

interatomic bonds, and

is the force constant that measures the strength of

interatomic bonds, and  is the mass involved in the oscillation) as proof that the typical

frequencies of lattice vibrations are very

much less than the vibration frequencies of simple molecules.

It follows, from

is the mass involved in the oscillation) as proof that the typical

frequencies of lattice vibrations are very

much less than the vibration frequencies of simple molecules.

It follows, from

, that the quantum energy levels of lattice vibrations are

far more closely spaced than the vibrational energy levels of gaseous molecules. Thus, it is

likely (and is, indeed, the case) that lattice vibrations are not frozen out at room temperature,

but, instead, make their full classical contribution to the molar specific heat of the solid. (See Section 5.5.8.)

, that the quantum energy levels of lattice vibrations are

far more closely spaced than the vibrational energy levels of gaseous molecules. Thus, it is

likely (and is, indeed, the case) that lattice vibrations are not frozen out at room temperature,

but, instead, make their full classical contribution to the molar specific heat of the solid. (See Section 5.5.8.)

, in equilibrium at

temperature

, in equilibrium at

temperature  [

[

resides in the kinetic energy of the oscillation,

and

resides in the kinetic energy of the oscillation,

and

resides in the potential energy].

Thus, the internal energy of the solid is

resides in the potential energy].

Thus, the internal energy of the solid is

.

It follows that the molar heat capacity at constant volume is

.

It follows that the molar heat capacity at constant volume is

joules/mole/degree. In fact, at room temperature, most

solids (in particular, metals)

have heat capacities that lie remarkably close to this value. This

fact was discovered

experimentally by Pierre Dulong and Alexis Petite at the beginning of the nineteenth century, and was used to

make some of the first

crude estimates of the molecular weights of solids. (If we know the molar heat capacity

of a substance

then we can easily work out how much of it corresponds to one mole, and

by weighing this amount, and then dividing the result by Avogadro's number,

we can then obtain an estimate of the molecular weight.)

joules/mole/degree. In fact, at room temperature, most

solids (in particular, metals)

have heat capacities that lie remarkably close to this value. This

fact was discovered

experimentally by Pierre Dulong and Alexis Petite at the beginning of the nineteenth century, and was used to

make some of the first

crude estimates of the molecular weights of solids. (If we know the molar heat capacity

of a substance

then we can easily work out how much of it corresponds to one mole, and

by weighing this amount, and then dividing the result by Avogadro's number,

we can then obtain an estimate of the molecular weight.)

, at constant pressure for various solids. The heat capacity at constant

volume is somewhat less than the constant pressure value, but not by much,

because solids

are fairly incompressible.

It can be seen that Dulong and Petite's law (i.e., that all solids have a molar heat capacities

close to

, at constant pressure for various solids. The heat capacity at constant

volume is somewhat less than the constant pressure value, but not by much,

because solids

are fairly incompressible.

It can be seen that Dulong and Petite's law (i.e., that all solids have a molar heat capacities

close to  joules/mole/degree) holds fairly well for metals.

However, the law fails badly for

diamond. This is not surprising. As is well known,

diamond is an extremely hard substance, so its interatomic bonds must be very strong, suggesting

that the force constant,

joules/mole/degree) holds fairly well for metals.

However, the law fails badly for

diamond. This is not surprising. As is well known,

diamond is an extremely hard substance, so its interatomic bonds must be very strong, suggesting

that the force constant,  , is large.

Diamond is also a fairly low-density substance, so the mass,

, is large.

Diamond is also a fairly low-density substance, so the mass,  , involved in

lattice vibrations is comparatively small. Both these facts suggest that the typical lattice vibration

frequency of diamond (

, involved in

lattice vibrations is comparatively small. Both these facts suggest that the typical lattice vibration

frequency of diamond (

) is high. In fact, the spacing between

the different vibrational energy

levels (which scales like

) is high. In fact, the spacing between

the different vibrational energy

levels (which scales like

) is sufficiently large in diamond for the vibrational

degrees of freedom

to be largely frozen out at room temperature. This accounts for the anomalously low

heat capacity of diamond in Table 5.3.

) is sufficiently large in diamond for the vibrational

degrees of freedom

to be largely frozen out at room temperature. This accounts for the anomalously low

heat capacity of diamond in Table 5.3.

at low temperatures by assuming that all of the normal

modes oscillate at the same frequency,

at low temperatures by assuming that all of the normal

modes oscillate at the same frequency,  (say). This approximation was first employed by

Einstein in a paper published in 1907. According to Equation (5.487),

the solid acts like a set

of

(say). This approximation was first employed by

Einstein in a paper published in 1907. According to Equation (5.487),

the solid acts like a set

of  independent oscillators which, making use of

Einstein's approximation, all vibrate at the same frequency.

We can use the quantum mechanical result (5.390) for the mean energy of a single

oscillator to write the internal energy

of the solid in the form

independent oscillators which, making use of

Einstein's approximation, all vibrate at the same frequency.

We can use the quantum mechanical result (5.390) for the mean energy of a single

oscillator to write the internal energy

of the solid in the form

![$\displaystyle U = 3\,N \left[\frac{1}{2} +

\frac{1}{\exp(\hbar\,\omega/k_B\,T) - 1} \right]\hbar\,\omega,$](img4387.png)

then the previous expression reduces to

then the previous expression reduces to

, after expansion of the exponential functions. Thus, the law of Dulong and

Petite is recovered for temperatures significantly in excess of the Einstein temperature.

On the other hand, if the temperature is sufficiently

low that

, after expansion of the exponential functions. Thus, the law of Dulong and

Petite is recovered for temperatures significantly in excess of the Einstein temperature.

On the other hand, if the temperature is sufficiently

low that

then the

exponential factors appearing in Equation (5.491) become very much larger than unity, giving

then the

exponential factors appearing in Equation (5.491) become very much larger than unity, giving

.

.

. The experimentally observed low-temperature

behavior is more like

. The experimentally observed low-temperature

behavior is more like

. The reason for this discrepancy is the crude

approximation

that all normal modes have the same frequency. In fact, long-wavelength modes have lower frequencies

than short-wavelength modes, so the former are much harder to freeze out than the latter

(because the spacing between quantum energy levels,

. The reason for this discrepancy is the crude

approximation

that all normal modes have the same frequency. In fact, long-wavelength modes have lower frequencies

than short-wavelength modes, so the former are much harder to freeze out than the latter

(because the spacing between quantum energy levels,

, is smaller in the former case).

The molar

heat capacity does not decrease with temperature as rapidly as suggested by Einstein's model

because these long-wavelength modes are able to make a significant contribution

to the heat capacity, even at very low

temperatures. A more realistic model of lattice vibrations was developed by

Peter Debye in 1912.

In the Debye model, the frequencies of the normal modes of vibration are estimated by treating

the solid as an isotropic continuous medium. This approach is reasonable because the only modes

that really matter at low temperatures are the long-wavelength modes; more explicitly, those whose

wavelengths greatly exceed the interatomic spacing. It is plausible that these modes are not

particularly

sensitive to the discrete nature of the solid. In other words, they are not sensitive to the fact that the solid is made up of atoms,

rather than being continuous.

, is smaller in the former case).

The molar

heat capacity does not decrease with temperature as rapidly as suggested by Einstein's model

because these long-wavelength modes are able to make a significant contribution

to the heat capacity, even at very low

temperatures. A more realistic model of lattice vibrations was developed by

Peter Debye in 1912.

In the Debye model, the frequencies of the normal modes of vibration are estimated by treating

the solid as an isotropic continuous medium. This approach is reasonable because the only modes

that really matter at low temperatures are the long-wavelength modes; more explicitly, those whose

wavelengths greatly exceed the interatomic spacing. It is plausible that these modes are not

particularly

sensitive to the discrete nature of the solid. In other words, they are not sensitive to the fact that the solid is made up of atoms,

rather than being continuous.

is the average sound speed.

The Debye approach consists in approximating the actual density of sound wave states,

is the average sound speed.

The Debye approach consists in approximating the actual density of sound wave states,

, by the density in a continuous medium,

, by the density in a continuous medium,

, not

only at low frequencies (long wavelengths) where these should be nearly the same, but

also at high frequencies where they may differ substantially. Suppose that we are

dealing with a solid consisting of

, not

only at low frequencies (long wavelengths) where these should be nearly the same, but

also at high frequencies where they may differ substantially. Suppose that we are

dealing with a solid consisting of  atoms. We know that there are

only

atoms. We know that there are

only  independent normal modes. It follows that we must cut off the

density of states above some critical frequency,

independent normal modes. It follows that we must cut off the

density of states above some critical frequency,  (say), otherwise we

will have too many modes. Thus, in the Debye approximation, the density

of normal modes takes the form

Here,

(say), otherwise we

will have too many modes. Thus, in the Debye approximation, the density

of normal modes takes the form

Here,  is termed the Debye frequency, and is chosen such that

the total number of normal modes is

is termed the Debye frequency, and is chosen such that

the total number of normal modes is  :

:

, which is clearly on the order of the interatomic spacing,

, which is clearly on the order of the interatomic spacing,

.

It follows that the cut-off of normal modes whose frequencies exceed the Debye frequency

is equivalent to a cut-off of normal modes whose wavelengths are less than the interatomic

spacing. Of course, it makes physical sense that such modes should be absent.

.

It follows that the cut-off of normal modes whose frequencies exceed the Debye frequency

is equivalent to a cut-off of normal modes whose wavelengths are less than the interatomic

spacing. Of course, it makes physical sense that such modes should be absent.

![$\displaystyle U = \int_0^\infty \rho_D(\omega)

\left[\frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{\exp(\hbar\, \omega/k_B\,T)-1}\right]\hbar\,\omega\,d\omega.$](img4406.png)

![$\displaystyle c_V =\frac{1}{\nu}\left(\frac{\partial U}{\partial T}\right)_V

= ...

...,\omega}

{[\exp(\hbar\,\omega/k_B\,T)-1]^{\,2}}\right\}

\hbar\,\omega\,d\omega.$](img4407.png)

![$\displaystyle c_V = \frac{k_B}{\nu}\int_0^{\omega_D} \frac{\exp(\hbar\,\omega/k...

...\omega/k_B\,T)-1]^{2}}\,

\frac{3 \,V}{2\pi^2 \,v_s^{\,3}}\,\omega^{2}\,d\omega,$](img4408.png)

.

According to Equation (5.498), the volume can be written

.

According to Equation (5.498), the volume can be written

, as

, as

. For small

. For small  , we can approximate

, we can approximate

as

as  in the integrand of Equation (5.505), so that

in the integrand of Equation (5.505), so that

. Consider, now, the

asymptotic limit in which

. Consider, now, the

asymptotic limit in which

. For large

. For large  ,

,

, Note that

, Note that  varies with temperature as

varies with temperature as  , in accordance with experimental

observation.

, in accordance with experimental

observation.

goes like

goes like  at low temperatures is quite well verified experimentally,

although it is sometimes necessary to go to temperatures as low as

at low temperatures is quite well verified experimentally,

although it is sometimes necessary to go to temperatures as low as

to obtain

this asymptotic behavior. Theoretically,

to obtain

this asymptotic behavior. Theoretically,  should be calculable from

Equation (5.498)

in terms of the sound speed in the solid, and the molar volume. Table 5.4 shows a

comparison of Debye temperatures evaluated by this means with temperatures obtained

empirically by fitting the law (5.510) to the low-temperature variation of the

heat capacity. It can be seen that there is fairly good agreement between the theoretical and

empirical Debye temperatures. This suggests that the Debye theory affords a good, though not

perfect, representation of the behavior of

should be calculable from

Equation (5.498)

in terms of the sound speed in the solid, and the molar volume. Table 5.4 shows a

comparison of Debye temperatures evaluated by this means with temperatures obtained

empirically by fitting the law (5.510) to the low-temperature variation of the

heat capacity. It can be seen that there is fairly good agreement between the theoretical and

empirical Debye temperatures. This suggests that the Debye theory affords a good, though not

perfect, representation of the behavior of  in solids over the entire temperature range.

in solids over the entire temperature range.

![\includegraphics[width=0.85\textwidth]{Chapter06/debye.eps}](img4426.png)