The conduction electrons in a metal are non-localized (i.e., they are

not tied to any particular atoms). In conventional metals, each atom contributes

a fixed number of such electrons (corresponding to its valency). To a first approximation, it is possible

to neglect the mutual interaction of the conduction electrons, because this

interaction

is largely shielded out by the stationary ions. The conduction electrons

can, therefore, be treated as an ideal gas. However, the number density of

such electrons in a metal far exceeds the number density of

molecules in a conventional gas.

Electrons are subject to the Pauli exclusion principle, according to which a given electron state can either be unoccupied, or singly occupied. (See Section 4.4.3.) The so-called Fermi energy is the energy at which electrons are available without doing work.

Thus, an electron state of energy  has an available free energy 0 when it is unoccupied, and an available free energy

has an available free energy 0 when it is unoccupied, and an available free energy

when it is occupied. According to the Boltzmann distribution (see Section 5.4.7), the relative probabilities of unoccupied and occupied

states are thus

when it is occupied. According to the Boltzmann distribution (see Section 5.4.7), the relative probabilities of unoccupied and occupied

states are thus  and

and

![$P(1)= \exp[-(\epsilon-\epsilon_F)/(k_B\,T)]$](img4429.png) , respectively, where

, respectively, where  is the temperature. (See Section 5.4.7.) Thus, the mean occupancy number of the state is

is the temperature. (See Section 5.4.7.) Thus, the mean occupancy number of the state is

|

(5.511) |

which reduces to

![$\displaystyle F(\epsilon) = \frac{1}{\exp[(\epsilon-\epsilon_F)/(k_B\,T)]+1}.$](img4431.png) |

(5.512) |

Here,

is termed the Fermi function.

is termed the Fermi function.

Let us investigate the behavior of the Fermi function as  varies. Here, the energy is measured from

its lowest possible value

varies. Here, the energy is measured from

its lowest possible value

.

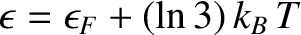

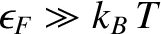

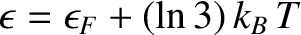

The Fermi energy for conduction electrons in a metal is

such that

.

The Fermi energy for conduction electrons in a metal is

such that

.

In this limit, if

.

In this limit, if

then

then

,

so that

,

so that

. On the other hand, if

. On the other hand, if

then

then

, so that

, so that

![$F(\epsilon)\simeq

\exp[-(\epsilon-\mu)/(k_B\,T)]$](img4439.png) falls off exponentially with increasing

falls off exponentially with increasing

. Note that

. Note that

when

when

. The transition region in which

. The transition region in which  goes from

a value close to unity to a value close to zero corresponds to an

energy interval of order

goes from

a value close to unity to a value close to zero corresponds to an

energy interval of order  , centered on

, centered on

. In fact,

. In fact,  when

when

, and

, and  when

when

. The behavior of the Fermi function is

illustrated in Figure 5.10.

. The behavior of the Fermi function is

illustrated in Figure 5.10.

Figure 5.10:

The Fermi function.

|

|

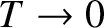

In the limit as

, the transition region becomes

infinitesimally narrow. In this case,

, the transition region becomes

infinitesimally narrow. In this case,  for

for

, and

, and

for

for

, as illustrated in Figure 5.10.

This is an obvious result, because when

, as illustrated in Figure 5.10.

This is an obvious result, because when  the conduction

electrons attain their lowest energy, or ground-state, configuration.

Because the Pauli exclusion principle requires that there be no

more than one electron per single-particle quantum state, the lowest

energy configuration is obtained by piling

electrons into the lowest available unoccupied states, until all of

the electrons are used up. Thus, the last electron added to the

pile has a quite considerable energy,

the conduction

electrons attain their lowest energy, or ground-state, configuration.

Because the Pauli exclusion principle requires that there be no

more than one electron per single-particle quantum state, the lowest

energy configuration is obtained by piling

electrons into the lowest available unoccupied states, until all of

the electrons are used up. Thus, the last electron added to the

pile has a quite considerable energy,

, because all of the

lower energy states are already occupied. Clearly, the exclusion principle

implies that free electrons in a metal possess a large mean energy, even at a temperature of absolute

zero.

, because all of the

lower energy states are already occupied. Clearly, the exclusion principle

implies that free electrons in a metal possess a large mean energy, even at a temperature of absolute

zero.

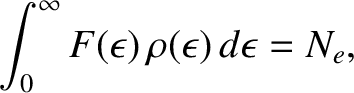

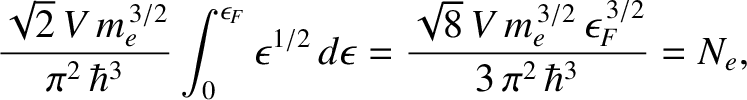

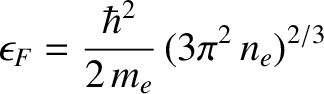

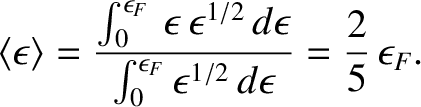

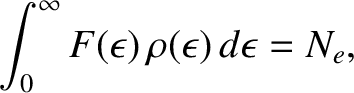

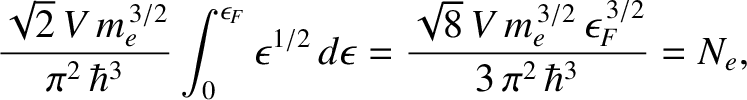

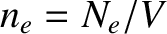

We can calculate the Fermi energy by equating the number of occupied electron states to the

total number of electrons in the metal,  . In other words,

. In other words,

|

(5.513) |

where

is the density of electron states specified in Equation (5.466). Assuming that

is the density of electron states specified in Equation (5.466). Assuming that

, we can make the approximation

, we can make the approximation

![$\displaystyle F(\epsilon) \simeq \left\{\begin{array}{lll}

1&~~~&0\leq\epsilon\leq \epsilon_F\\ [0.5ex]

0&&\epsilon>\epsilon_F\end{array}\right..$](img4455.png) |

(5.514) |

Thus, making use of Equation (5.466), we obtain

|

(5.515) |

which can be rearranged to give

|

(5.516) |

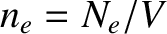

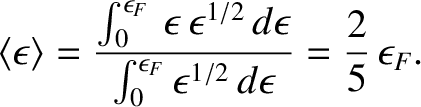

where  is the number density of conduction electrons. The mean electron energy is

is the number density of conduction electrons. The mean electron energy is

|

(5.517) |

(See Section 4.4.3.)

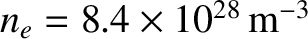

Copper at room temperature has a number density of conduction electrons of

. According to Equation (5.516), the corresponding Fermi energy is

. According to Equation (5.516), the corresponding Fermi energy is

|

(5.518) |

The associated Fermi temperature is

|

(5.519) |

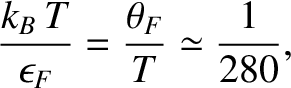

Thus, at room temperature,  K, we obtain

K, we obtain

|

(5.520) |

which confirms that

for conduction electrons in a metal.

for conduction electrons in a metal.

Figure 5.11:

Approximate Fermi function.

|

|

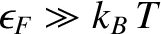

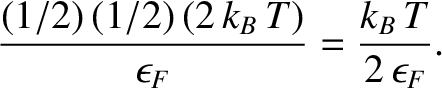

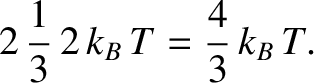

Let us crudely approximate the Fermi function at finite temperature in the fashion shown in Figure 5.11.

As can be seen from the figure, the proportion of thermally excited electrons is the ratio of the area of a triangle of height  and

base

and

base  to that of a rectangle of height 1 and base

to that of a rectangle of height 1 and base

. In other words,

. In other words,

|

(5.521) |

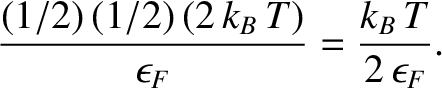

Now, the centroid of a right-angled triangle is  rd of the distance along its base from the right-angle. Thus, the

mean energy of the excited electrons increases by

rd of the distance along its base from the right-angle. Thus, the

mean energy of the excited electrons increases by

|

(5.522) |

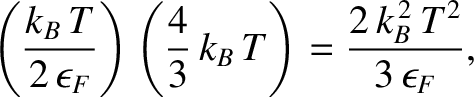

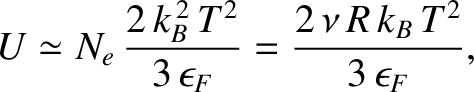

Hence, the thermal energy per conduction electron is

|

(5.523) |

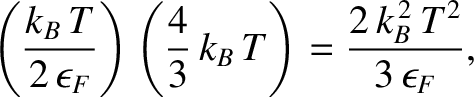

which implies that the internal energy (i.e., the difference between the energy at a finite temperature and the energy at absolute zero) of the conduction electrons is

|

(5.524) |

where  is the number of moles of electrons.

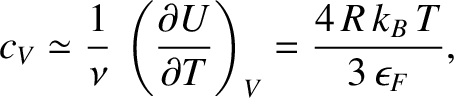

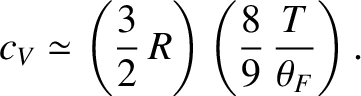

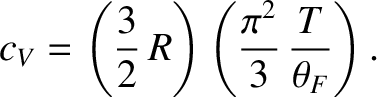

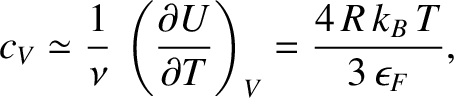

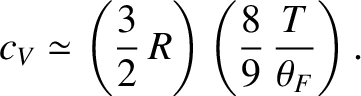

Finally, the molar specific heat of the electrons at constant volume is

is the number of moles of electrons.

Finally, the molar specific heat of the electrons at constant volume is

|

(5.525) |

which can also be written

|

(5.526) |

The exact result is

|

(5.527) |

Thus, we conclude that the contribution of the conduction electrons to the molar specific heat capacity of a

metal is proportional to the temperature. However, this contribution is much less that the classical contribution,  ,

predicted by the equipartition theorem (see Section 5.5.5), given that each conduction electron possesses three translational

degrees of freedom. This is the case because the conduction electrons in a metal are highly degenerate. (See Section 4.4.3.)

In fact, Equations (5.520) and (5.527) imply that the contribution of the conduction electrons to the molar specific heat of copper at room temperature is a factor 85 times smaller than the classical

contribution.

,

predicted by the equipartition theorem (see Section 5.5.5), given that each conduction electron possesses three translational

degrees of freedom. This is the case because the conduction electrons in a metal are highly degenerate. (See Section 4.4.3.)

In fact, Equations (5.520) and (5.527) imply that the contribution of the conduction electrons to the molar specific heat of copper at room temperature is a factor 85 times smaller than the classical

contribution.

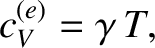

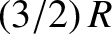

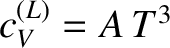

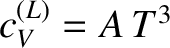

Using the superscript  to denote the electronic

specific heat due to conduction electrons, the molar specific heat of such electrons can be written

to denote the electronic

specific heat due to conduction electrons, the molar specific heat of such electrons can be written

|

(5.528) |

where  is a (positive) constant of proportionality.

At room temperature,

is a (positive) constant of proportionality.

At room temperature,  is completely masked by the much

larger specific heat,

is completely masked by the much

larger specific heat,  , due to lattice vibrations. However, at

very low temperatures,

, due to lattice vibrations. However, at

very low temperatures,

, where

, where  is a (positive)

constant of proportionality. (See Section 5.6.5.) Clearly,

at low temperatures,

is a (positive)

constant of proportionality. (See Section 5.6.5.) Clearly,

at low temperatures,

approaches zero far more rapidly than

the electronic specific heat, as

approaches zero far more rapidly than

the electronic specific heat, as  is reduced. Hence, it should be possible

to measure the electronic contribution to the molar specific

heat at low temperatures.

is reduced. Hence, it should be possible

to measure the electronic contribution to the molar specific

heat at low temperatures.

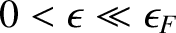

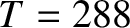

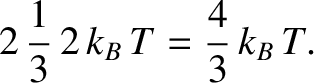

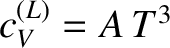

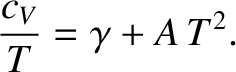

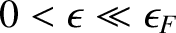

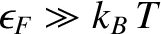

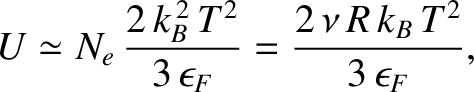

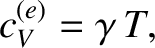

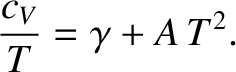

Figure: 5.12

The low-temperature heat capacity of potassium, plotted as  versus

versus

. The straight-line shows the fit

. The straight-line shows the fit

.

.

|

|

The total molar specific heat of a metal at low temperatures takes the

form

|

(5.529) |

Hence,

|

(5.530) |

It follows that a plot of  versus

versus  should yield a

straight-line whose intercept on the vertical axis gives the

coefficient

should yield a

straight-line whose intercept on the vertical axis gives the

coefficient  . Figure 5.12 shows such a plot.

The fact that a good straight-line, with a non-zero intercept, is obtained verifies that the temperature

dependence of the heat capacity predicted by Equation (5.529) is indeed

correct.

. Figure 5.12 shows such a plot.

The fact that a good straight-line, with a non-zero intercept, is obtained verifies that the temperature

dependence of the heat capacity predicted by Equation (5.529) is indeed

correct.

has an available free energy 0 when it is unoccupied, and an available free energy

has an available free energy 0 when it is unoccupied, and an available free energy

when it is occupied. According to the Boltzmann distribution (see Section 5.4.7), the relative probabilities of unoccupied and occupied

states are thus

when it is occupied. According to the Boltzmann distribution (see Section 5.4.7), the relative probabilities of unoccupied and occupied

states are thus  and

and

![$P(1)= \exp[-(\epsilon-\epsilon_F)/(k_B\,T)]$](img4429.png) , respectively, where

, respectively, where  is the temperature. (See Section 5.4.7.) Thus, the mean occupancy number of the state is

is the temperature. (See Section 5.4.7.) Thus, the mean occupancy number of the state is

![$\displaystyle F(\epsilon) = \frac{1}{\exp[(\epsilon-\epsilon_F)/(k_B\,T)]+1}.$](img4431.png)

is termed the Fermi function.

is termed the Fermi function.

varies. Here, the energy is measured from

its lowest possible value

varies. Here, the energy is measured from

its lowest possible value

.

The Fermi energy for conduction electrons in a metal is

such that

.

The Fermi energy for conduction electrons in a metal is

such that

.

In this limit, if

.

In this limit, if

then

then

,

so that

,

so that

. On the other hand, if

. On the other hand, if

then

then

, so that

, so that

![$F(\epsilon)\simeq

\exp[-(\epsilon-\mu)/(k_B\,T)]$](img4439.png) falls off exponentially with increasing

falls off exponentially with increasing

. Note that

. Note that

when

when

. The transition region in which

. The transition region in which  goes from

a value close to unity to a value close to zero corresponds to an

energy interval of order

goes from

a value close to unity to a value close to zero corresponds to an

energy interval of order  , centered on

, centered on

. In fact,

. In fact,  when

when

, and

, and  when

when

. The behavior of the Fermi function is

illustrated in Figure 5.10.

. The behavior of the Fermi function is

illustrated in Figure 5.10.

, the transition region becomes

infinitesimally narrow. In this case,

, the transition region becomes

infinitesimally narrow. In this case,  for

for

, and

, and

for

for

, as illustrated in Figure 5.10.

This is an obvious result, because when

, as illustrated in Figure 5.10.

This is an obvious result, because when  the conduction

electrons attain their lowest energy, or ground-state, configuration.

Because the Pauli exclusion principle requires that there be no

more than one electron per single-particle quantum state, the lowest

energy configuration is obtained by piling

electrons into the lowest available unoccupied states, until all of

the electrons are used up. Thus, the last electron added to the

pile has a quite considerable energy,

the conduction

electrons attain their lowest energy, or ground-state, configuration.

Because the Pauli exclusion principle requires that there be no

more than one electron per single-particle quantum state, the lowest

energy configuration is obtained by piling

electrons into the lowest available unoccupied states, until all of

the electrons are used up. Thus, the last electron added to the

pile has a quite considerable energy,

, because all of the

lower energy states are already occupied. Clearly, the exclusion principle

implies that free electrons in a metal possess a large mean energy, even at a temperature of absolute

zero.

, because all of the

lower energy states are already occupied. Clearly, the exclusion principle

implies that free electrons in a metal possess a large mean energy, even at a temperature of absolute

zero.

. In other words,

. In other words,

is the density of electron states specified in Equation (5.466). Assuming that

is the density of electron states specified in Equation (5.466). Assuming that

, we can make the approximation

, we can make the approximation

![$\displaystyle F(\epsilon) \simeq \left\{\begin{array}{lll}

1&~~~&0\leq\epsilon\leq \epsilon_F\\ [0.5ex]

0&&\epsilon>\epsilon_F\end{array}\right..$](img4455.png)

is the number density of conduction electrons. The mean electron energy is

is the number density of conduction electrons. The mean electron energy is

. According to Equation (5.516), the corresponding Fermi energy is

. According to Equation (5.516), the corresponding Fermi energy is

K, we obtain

which confirms that

K, we obtain

which confirms that

for conduction electrons in a metal.

for conduction electrons in a metal.

and

base

and

base  to that of a rectangle of height 1 and base

to that of a rectangle of height 1 and base

. In other words,

. In other words,

rd of the distance along its base from the right-angle. Thus, the

mean energy of the excited electrons increases by

rd of the distance along its base from the right-angle. Thus, the

mean energy of the excited electrons increases by

is the number of moles of electrons.

Finally, the molar specific heat of the electrons at constant volume is

is the number of moles of electrons.

Finally, the molar specific heat of the electrons at constant volume is

,

predicted by the equipartition theorem (see Section 5.5.5), given that each conduction electron possesses three translational

degrees of freedom. This is the case because the conduction electrons in a metal are highly degenerate. (See Section 4.4.3.)

In fact, Equations (5.520) and (5.527) imply that the contribution of the conduction electrons to the molar specific heat of copper at room temperature is a factor 85 times smaller than the classical

contribution.

,

predicted by the equipartition theorem (see Section 5.5.5), given that each conduction electron possesses three translational

degrees of freedom. This is the case because the conduction electrons in a metal are highly degenerate. (See Section 4.4.3.)

In fact, Equations (5.520) and (5.527) imply that the contribution of the conduction electrons to the molar specific heat of copper at room temperature is a factor 85 times smaller than the classical

contribution.

to denote the electronic

specific heat due to conduction electrons, the molar specific heat of such electrons can be written

to denote the electronic

specific heat due to conduction electrons, the molar specific heat of such electrons can be written

is a (positive) constant of proportionality.

At room temperature,

is a (positive) constant of proportionality.

At room temperature,  is completely masked by the much

larger specific heat,

is completely masked by the much

larger specific heat,  , due to lattice vibrations. However, at

very low temperatures,

, due to lattice vibrations. However, at

very low temperatures,

, where

, where  is a (positive)

constant of proportionality. (See Section 5.6.5.) Clearly,

at low temperatures,

is a (positive)

constant of proportionality. (See Section 5.6.5.) Clearly,

at low temperatures,

approaches zero far more rapidly than

the electronic specific heat, as

approaches zero far more rapidly than

the electronic specific heat, as  is reduced. Hence, it should be possible

to measure the electronic contribution to the molar specific

heat at low temperatures.

is reduced. Hence, it should be possible

to measure the electronic contribution to the molar specific

heat at low temperatures.

![\includegraphics[width=0.85\textwidth]{Chapter06/metal.eps}](img4479.png)

versus

versus  should yield a

straight-line whose intercept on the vertical axis gives the

coefficient

should yield a

straight-line whose intercept on the vertical axis gives the

coefficient  . Figure 5.12 shows such a plot.

The fact that a good straight-line, with a non-zero intercept, is obtained verifies that the temperature

dependence of the heat capacity predicted by Equation (5.529) is indeed

correct.

. Figure 5.12 shows such a plot.

The fact that a good straight-line, with a non-zero intercept, is obtained verifies that the temperature

dependence of the heat capacity predicted by Equation (5.529) is indeed

correct.