Equipartition Theorem

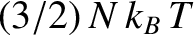

The internal energy of a monatomic ideal gas containing  atoms is

atoms is

. (See Section 5.2.3.)

This implies that each atom possess, on average,

. (See Section 5.2.3.)

This implies that each atom possess, on average,

units of energy.

Monatomic particles have only three translational degrees

of freedom, corresponding to

their motion in three dimensions. They possess no internal

rotational or vibrational degrees of freedom. Thus, the mean energy per degree of

freedom in a monatomic ideal gas is

units of energy.

Monatomic particles have only three translational degrees

of freedom, corresponding to

their motion in three dimensions. They possess no internal

rotational or vibrational degrees of freedom. Thus, the mean energy per degree of

freedom in a monatomic ideal gas is

. In fact,

this is a special case of a more general result. Let us now try to prove this result.

. In fact,

this is a special case of a more general result. Let us now try to prove this result.

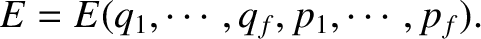

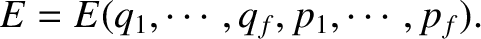

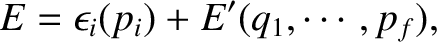

Suppose that the energy of a

system is determined by  coordinates,

coordinates,  ,

and

,

and  corresponding momenta,

corresponding momenta,  , so that

, so that

|

(5.366) |

Suppose further that:

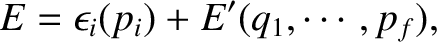

- The total energy splits additively into the form

|

(5.367) |

where

involves only one variable,

involves only one variable,  , and the remaining part,

, and the remaining part,

, does not depend on

, does not depend on  .

.

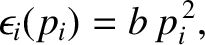

- The function

is quadratic in

is quadratic in  , so that

, so that

|

(5.368) |

where  is a constant.

is a constant.

The most common situation in which the previous assumptions are valid is where

is a momentum. This is because the kinetic energy is usually a quadratic

function of each momentum component, whereas the potential energy does not

involve the momenta at all. However, if a coordinate,

is a momentum. This is because the kinetic energy is usually a quadratic

function of each momentum component, whereas the potential energy does not

involve the momenta at all. However, if a coordinate,  , were to satisfy

assumptions 1 and 2 then the theorem that we are about to establish would hold just

as well.

, were to satisfy

assumptions 1 and 2 then the theorem that we are about to establish would hold just

as well.

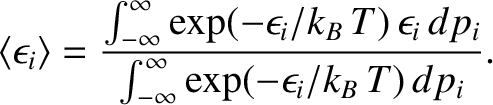

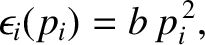

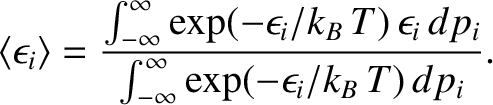

What is the mean value of

in thermal equilibrium if conditions

1 and 2 are satisfied? If the system is in equilibrium at absolute temperature

in thermal equilibrium if conditions

1 and 2 are satisfied? If the system is in equilibrium at absolute temperature

then it is distributed according to the Boltzmann probability

distribution. (See Section 5.4.7.) In the classical approximation,

the mean value of

then it is distributed according to the Boltzmann probability

distribution. (See Section 5.4.7.) In the classical approximation,

the mean value of

is expressed in terms of

integrals over all phase-space (see Section 5.4.4):

is expressed in terms of

integrals over all phase-space (see Section 5.4.4):

![$\displaystyle \langle\epsilon_i\rangle = \frac{

\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \exp[-E...

...

{\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \exp[- E(q_1,\cdots, p_f)/k_B\,T]\,

dq_1\cdots dp_f}.$](img4127.png) |

(5.369) |

Condition 1 gives

where use has been made of the multiplicative property of the exponential function,

and where the final integrals in both the numerator and denominator extend over

all variables,

and

and  , except for

, except for  . These integrals are equal and, thus, cancel.

Hence,

. These integrals are equal and, thus, cancel.

Hence,

|

(5.371) |

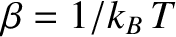

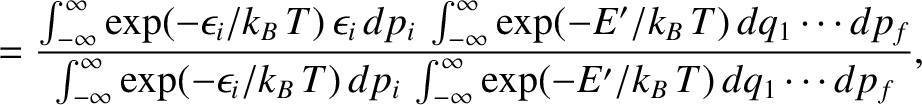

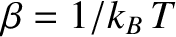

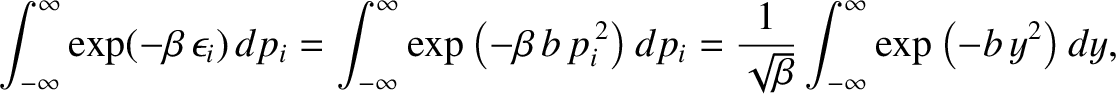

This expression can be simplified further because, writing

,

,

![$\displaystyle \int_{-\infty}^\infty

\exp(-\beta \,\epsilon_i)\,\epsilon_i\, dp_...

...ial \beta}

\left[\int_{-\infty}^\infty \exp(-\beta \,\epsilon_i)\, dp_i\right],$](img4133.png) |

(5.372) |

so

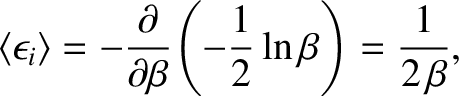

![$\displaystyle \langle\epsilon_i\rangle = - \frac{\partial}{\partial\beta}

\ln\left[\int_{-\infty}^\infty \exp(-\beta \,\epsilon_i)\,

dp_i\right].$](img4134.png) |

(5.373) |

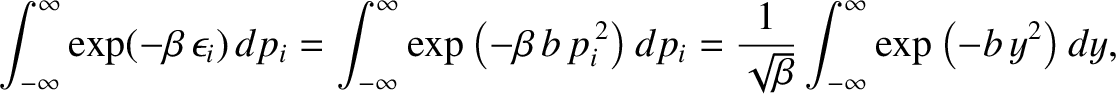

According to condition 2,

|

(5.374) |

where

. Thus,

. Thus,

|

(5.375) |

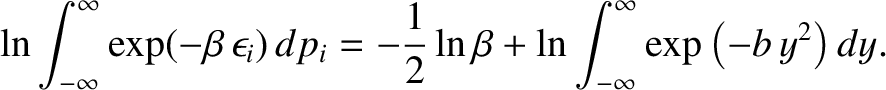

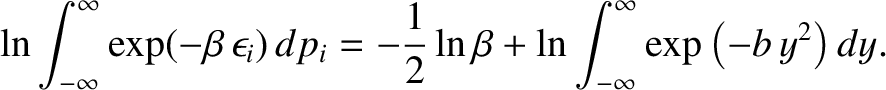

Note that the integral on the right-hand side is independent of  . It follows

from Equation (5.373) that

. It follows

from Equation (5.373) that

|

(5.376) |

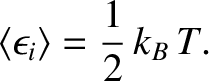

giving

|

(5.377) |

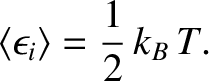

This result is known as the equipartition theorem.

It states that the mean value of every independent

quadratic term in the energy is equal to

. If all terms in the energy are quadratic

then the mean energy is spread equally over all degrees of freedom. (Hence, the

name “equipartition.”)

. If all terms in the energy are quadratic

then the mean energy is spread equally over all degrees of freedom. (Hence, the

name “equipartition.”)

atoms is

atoms is

. (See Section 5.2.3.)

This implies that each atom possess, on average,

. (See Section 5.2.3.)

This implies that each atom possess, on average,

units of energy.

Monatomic particles have only three translational degrees

of freedom, corresponding to

their motion in three dimensions. They possess no internal

rotational or vibrational degrees of freedom. Thus, the mean energy per degree of

freedom in a monatomic ideal gas is

units of energy.

Monatomic particles have only three translational degrees

of freedom, corresponding to

their motion in three dimensions. They possess no internal

rotational or vibrational degrees of freedom. Thus, the mean energy per degree of

freedom in a monatomic ideal gas is

. In fact,

this is a special case of a more general result. Let us now try to prove this result.

. In fact,

this is a special case of a more general result. Let us now try to prove this result.

coordinates,

coordinates,  ,

and

,

and  corresponding momenta,

corresponding momenta,  , so that

, so that

involves only one variable,

involves only one variable,  , and the remaining part,

, and the remaining part,

, does not depend on

, does not depend on  .

.

is quadratic in

is quadratic in  , so that

, so that

is a constant.

is a constant.

is a momentum. This is because the kinetic energy is usually a quadratic

function of each momentum component, whereas the potential energy does not

involve the momenta at all. However, if a coordinate,

is a momentum. This is because the kinetic energy is usually a quadratic

function of each momentum component, whereas the potential energy does not

involve the momenta at all. However, if a coordinate,  , were to satisfy

assumptions 1 and 2 then the theorem that we are about to establish would hold just

as well.

, were to satisfy

assumptions 1 and 2 then the theorem that we are about to establish would hold just

as well.

in thermal equilibrium if conditions

1 and 2 are satisfied? If the system is in equilibrium at absolute temperature

in thermal equilibrium if conditions

1 and 2 are satisfied? If the system is in equilibrium at absolute temperature

then it is distributed according to the Boltzmann probability

distribution. (See Section 5.4.7.) In the classical approximation,

the mean value of

then it is distributed according to the Boltzmann probability

distribution. (See Section 5.4.7.) In the classical approximation,

the mean value of

is expressed in terms of

integrals over all phase-space (see Section 5.4.4):

is expressed in terms of

integrals over all phase-space (see Section 5.4.4):

![$\displaystyle \langle\epsilon_i\rangle = \frac{

\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \exp[-E...

...

{\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \exp[- E(q_1,\cdots, p_f)/k_B\,T]\,

dq_1\cdots dp_f}.$](img4127.png)

![$\displaystyle =\frac{

\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \exp[-(\epsilon_i + E')/k_B\,T]\,...

...p_f}

{\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \exp[-(\epsilon_i + E')/k_B\,T]\,dq_1\cdots dp_f}$](img4129.png)

and

and  , except for

, except for  . These integrals are equal and, thus, cancel.

Hence,

. These integrals are equal and, thus, cancel.

Hence,

,

,

![$\displaystyle \int_{-\infty}^\infty

\exp(-\beta \,\epsilon_i)\,\epsilon_i\, dp_...

...ial \beta}

\left[\int_{-\infty}^\infty \exp(-\beta \,\epsilon_i)\, dp_i\right],$](img4133.png)

. Thus,

. Thus,

. It follows

from Equation (5.373) that

. It follows

from Equation (5.373) that

. If all terms in the energy are quadratic

then the mean energy is spread equally over all degrees of freedom. (Hence, the

name “equipartition.”)

. If all terms in the energy are quadratic

then the mean energy is spread equally over all degrees of freedom. (Hence, the

name “equipartition.”)