Specific Heat Capacity

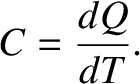

Suppose that we add an amount of heat  to an ideal gas causing its temperature to rise by

to an ideal gas causing its temperature to rise by  . The

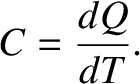

specific heat capacity of the gas is defined

. The

specific heat capacity of the gas is defined

|

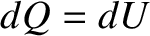

(5.103) |

In fact, an ideal gas possesses a number of different specific heat capacities depending on what is

held constant as heat is added to the system. Suppose that the volume is held constant. It follows

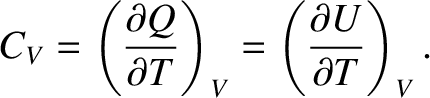

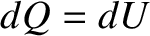

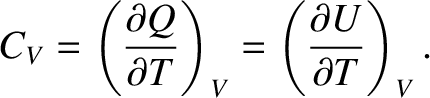

from Equation (5.102) that  . Hence, the specific heat capacity at constant volume of the gas is

. Hence, the specific heat capacity at constant volume of the gas is

|

(5.104) |

However, according to Joule's second law, which was established experimentally by James Joule in 1843,

the internal energy of an ideal gas depends on its temperature alone, and is independent of the volume or pressure.

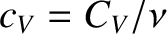

We also expect  to be an extensive quantity.

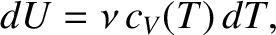

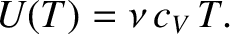

It follows that

to be an extensive quantity.

It follows that

|

(5.105) |

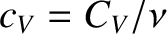

where

is termed the molar specific heat capacity at constant volume, and is an intensive quantity.

In fact,

is termed the molar specific heat capacity at constant volume, and is an intensive quantity.

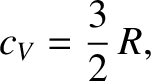

In fact,  is constant for an idea gas. For a monatomic gas,

is constant for an idea gas. For a monatomic gas,

|

(5.106) |

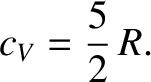

whereas for a diatomic gas,

|

(5.107) |

(See Sections 5.3.6 and 5.5.8.)

In both cases, Equation (5.105) can be integrated to give

|

(5.108) |

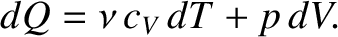

Consider the specific heat capacity of an ideal gas at constant pressure.

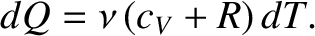

Making use of Equations (5.102) and (5.105),

|

(5.109) |

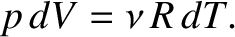

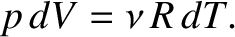

However, at constant pressure, the ideal gas law, (5.97), yields

|

(5.110) |

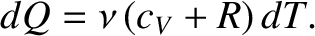

The previous two equations give

|

(5.111) |

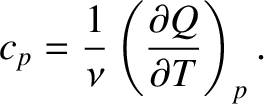

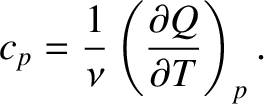

Now, the molar specific heat capacity at constant pressure of an ideal gas is

|

(5.112) |

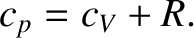

Hence, we deduce that

|

(5.113) |

Note that the specific heat capacity at constant pressure is greater than that at constant volume, because

some of the heat energy added to a gas held at constant pressure is consumed by the work that the gas does on its surroundings, in order to expand its volume slightly, and, therefore, does not lead to an increase in the internal energy (i.e.,

temperature) of the gas. On the other hand, for a gas held at constant volume, all of the added heat energy goes to

increase its internal energy.

to an ideal gas causing its temperature to rise by

to an ideal gas causing its temperature to rise by  . The

specific heat capacity of the gas is defined

. The

specific heat capacity of the gas is defined

. Hence, the specific heat capacity at constant volume of the gas is

. Hence, the specific heat capacity at constant volume of the gas is

to be an extensive quantity.

It follows that

where

to be an extensive quantity.

It follows that

where

is termed the molar specific heat capacity at constant volume, and is an intensive quantity.

In fact,

is termed the molar specific heat capacity at constant volume, and is an intensive quantity.

In fact,  is constant for an idea gas. For a monatomic gas,

whereas for a diatomic gas,

(See Sections 5.3.6 and 5.5.8.)

In both cases, Equation (5.105) can be integrated to give

is constant for an idea gas. For a monatomic gas,

whereas for a diatomic gas,

(See Sections 5.3.6 and 5.5.8.)

In both cases, Equation (5.105) can be integrated to give