Next: Maxwell Velocity Distribution Up: Applications of Statistical Mechanics Previous: Specific Heat Capacties

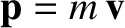

and momentum

and momentum

then its kinetic energy of translation is

The kinetic energy of other molecules does not involve the momentum,

then its kinetic energy of translation is

The kinetic energy of other molecules does not involve the momentum,  ,

of this particular molecule.

Moreover, the potential energy of interaction between molecules

depends only on their position coordinates, and is, thus, independent of

,

of this particular molecule.

Moreover, the potential energy of interaction between molecules

depends only on their position coordinates, and is, thus, independent of

. Any internal rotational, vibrational, electronic, or nuclear degrees

of freedom of the molecule also do not involve

. Any internal rotational, vibrational, electronic, or nuclear degrees

of freedom of the molecule also do not involve  . Hence, the essential

conditions of the equipartition theorem are satisfied. (At least, in the classical

approximation.) Because Equation (5.400) contains three independent

quadratic terms, there

are clearly three degrees of freedom associated with translation (one for each

dimension of space), so the translational contribution to the molar heat capacity

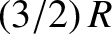

of gases is

. Hence, the essential

conditions of the equipartition theorem are satisfied. (At least, in the classical

approximation.) Because Equation (5.400) contains three independent

quadratic terms, there

are clearly three degrees of freedom associated with translation (one for each

dimension of space), so the translational contribution to the molar heat capacity

of gases is

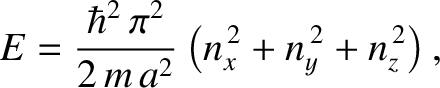

Suppose that our gas is contained in a cubic enclosure of dimensions  . According

to Schrödinger's equation, the quantized translational

energy levels of an individual molecule are given by

. According

to Schrödinger's equation, the quantized translational

energy levels of an individual molecule are given by

|

(5.402) |

,

,  , and

, and  are positive-integer quantum numbers. (See Section 4.4.2.) Clearly, the

spacing between the energy levels can be made arbitrarily small by increasing the

size of the enclosure. This implies that translational degrees of freedom can

be treated classically, so that

Equation (5.401) is always valid. (Except very close to absolute zero.)

We conclude that all

gases possess a minimum molar heat capacity of

are positive-integer quantum numbers. (See Section 4.4.2.) Clearly, the

spacing between the energy levels can be made arbitrarily small by increasing the

size of the enclosure. This implies that translational degrees of freedom can

be treated classically, so that

Equation (5.401) is always valid. (Except very close to absolute zero.)

We conclude that all

gases possess a minimum molar heat capacity of  due to the

translational degrees of freedom of their constituent molecules.

due to the

translational degrees of freedom of their constituent molecules.

The electronic degrees of freedom of gas molecules (i.e., the possible

configurations of electrons orbiting the atomic nuclei) typically give rise

to absorption and emission in the

ultraviolet or visible regions of the spectrum. It follows from Table 5.1 that

electronic degrees of freedom are frozen out at room temperature. Similarly,

nuclear degrees of freedom (i.e., the possible configurations of protons

and neutrons in the atomic nuclei) are frozen out because they are associated

with absorption and emission in the X-ray and  -ray regions of the

electromagnetic spectrum. In fact, the only additional degrees of freedom

that we need worry about for gases are rotational and vibrational degrees of freedom.

These typically give rise to absorption lines in the infrared region of the

spectrum.

-ray regions of the

electromagnetic spectrum. In fact, the only additional degrees of freedom

that we need worry about for gases are rotational and vibrational degrees of freedom.

These typically give rise to absorption lines in the infrared region of the

spectrum.

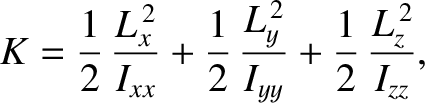

The rotational kinetic energy of a molecule tumbling in space can be written

|

(5.403) |

-,

-,  -, and

-, and  -axes are the so called principal axes of rotation

of the molecule (these are mutually perpendicular),

-axes are the so called principal axes of rotation

of the molecule (these are mutually perpendicular),  ,

,  ,

and

,

and  are the angular momenta about these axes, and

are the angular momenta about these axes, and

,

,  , and

, and  are the principal moments of inertia about these

axes. (See Sections 1.7.2 and 1.7.3.) No other degrees of freedom depend on the angular momenta. Because the kinetic energy of rotation is the sum of three quadratic

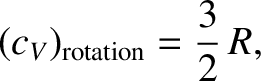

terms, the rotational contribution to the molar heat capacity of gases

is

are the principal moments of inertia about these

axes. (See Sections 1.7.2 and 1.7.3.) No other degrees of freedom depend on the angular momenta. Because the kinetic energy of rotation is the sum of three quadratic

terms, the rotational contribution to the molar heat capacity of gases

is

|

(5.404) |

, where

, where  is the molecular mass, and

is the molecular mass, and

is the typical interatomic spacing in the molecule.

A special case arises if the molecule is linear

(e.g., if the molecule is diatomic). In this case, one of the principal axes lies

along the line of centers of the atoms. The moment of inertia about this axis

is of order

is the typical interatomic spacing in the molecule.

A special case arises if the molecule is linear

(e.g., if the molecule is diatomic). In this case, one of the principal axes lies

along the line of centers of the atoms. The moment of inertia about this axis

is of order

, where

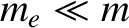

, where  is the electron mass. (See Section 5.3.6.) Because

is the electron mass. (See Section 5.3.6.) Because

, it follows that the moment of inertia about the line of

centers is minuscule compared to the moments of inertia about the other two

principal axes. In quantum mechanics, angular momentum is quantized in units

of

, it follows that the moment of inertia about the line of

centers is minuscule compared to the moments of inertia about the other two

principal axes. In quantum mechanics, angular momentum is quantized in units

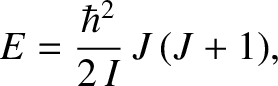

of  . The energy levels of a rigid rotator spinning about a principal axis are written

. The energy levels of a rigid rotator spinning about a principal axis are written

|

(5.405) |

is the moment of inertia, and

is the moment of inertia, and  is

a non-negative integer. Note the inverse dependence of the spacing between energy levels

on the moment

of inertia. It is clear that, for the case of a linear molecule, the rotational

degree of freedom associated with spinning along the line of centers of the

atoms is frozen out at room

temperature, given the very small moment of inertia along this axis, and, hence,

the very widely spaced rotational energy levels.

Thus, the rotational contribution to the molar heat capacity of a diatomic gas is

is

a non-negative integer. Note the inverse dependence of the spacing between energy levels

on the moment

of inertia. It is clear that, for the case of a linear molecule, the rotational

degree of freedom associated with spinning along the line of centers of the

atoms is frozen out at room

temperature, given the very small moment of inertia along this axis, and, hence,

the very widely spaced rotational energy levels.

Thus, the rotational contribution to the molar heat capacity of a diatomic gas is

|

(5.406) |

Classically, the vibrational degrees of freedom of a molecule are studied by

standard normal mode analysis of the

molecular

structure. Each normal mode behaves like an

independent harmonic oscillator, and, therefore,

contributes  to the molar specific heat of the gas [

to the molar specific heat of the gas [ from the

kinetic energy of vibration, and

from the

kinetic energy of vibration, and  from the potential energy of

vibration]. A molecule containing

from the potential energy of

vibration]. A molecule containing  atoms has

atoms has  normal modes of vibration.

For instance, a diatomic molecule has just one normal mode (corresponding to

periodic stretching of the bond between the two atoms). Thus, the classical

contribution to the specific heat from vibrational degrees of freedom is

normal modes of vibration.

For instance, a diatomic molecule has just one normal mode (corresponding to

periodic stretching of the bond between the two atoms). Thus, the classical

contribution to the specific heat from vibrational degrees of freedom is

|

(5.407) |

So, do any of the rotational and vibrational degrees of freedom

actually make a contribution to the specific heats of gases at room temperature,

once quantum effects have been taken into consideration? We can answer this

question by

examining just one piece of data. Figure 5.4 shows the

infrared absorption spectrum of hydrogen chloride gas. The absorption lines correspond

to simultaneous transitions between different vibrational and rotational energy

levels. Hence, this is usually called a vibration-rotation spectrum. The missing

line at about  microns corresponds to a pure vibrational transition from the

ground state to the first excited state.

(Pure vibrational transitions are

forbidden; hydrogen chloride molecules always have to simultaneously change their rotational energy level if they are to couple effectively to electromagnetic radiation.)

The longer wavelength absorption lines correspond to vibrational transitions in

which there is a simultaneous decrease in the rotational energy level.

Likewise, the

shorter wavelength absorption lines correspond to vibrational transitions in which

there is a simultaneous increase in the rotational energy level. It is clear that

the rotational energy levels are more closely spaced than the vibrational energy

levels. The pure vibrational transition gives rise to absorption at

about

microns corresponds to a pure vibrational transition from the

ground state to the first excited state.

(Pure vibrational transitions are

forbidden; hydrogen chloride molecules always have to simultaneously change their rotational energy level if they are to couple effectively to electromagnetic radiation.)

The longer wavelength absorption lines correspond to vibrational transitions in

which there is a simultaneous decrease in the rotational energy level.

Likewise, the

shorter wavelength absorption lines correspond to vibrational transitions in which

there is a simultaneous increase in the rotational energy level. It is clear that

the rotational energy levels are more closely spaced than the vibrational energy

levels. The pure vibrational transition gives rise to absorption at

about  microns, which corresponds to infrared radiation of frequency

microns, which corresponds to infrared radiation of frequency

hertz with an associated

radiation “temperature” of 4,100 K. We

conclude that

the vibrational degrees of freedom of hydrogen chloride, or any other small molecule,

are frozen out at room temperature. The rotational transitions split the

vibrational lines by about

hertz with an associated

radiation “temperature” of 4,100 K. We

conclude that

the vibrational degrees of freedom of hydrogen chloride, or any other small molecule,

are frozen out at room temperature. The rotational transitions split the

vibrational lines by about  microns. This implies that pure rotational

transitions would be associated with infrared radiation of frequency

microns. This implies that pure rotational

transitions would be associated with infrared radiation of frequency

hertz and corresponding

radiation “temperature” 240 K. We

conclude that the rotational degrees of freedom of hydrogen chloride, or any other small

molecule, are not frozen out at room temperature, and probably contribute the

classical

hertz and corresponding

radiation “temperature” 240 K. We

conclude that the rotational degrees of freedom of hydrogen chloride, or any other small

molecule, are not frozen out at room temperature, and probably contribute the

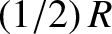

classical  to the molar specific heat. There is one proviso, however.

Linear molecules (like hydrogen chloride) effectively only have two rotational degrees of

freedom (instead of the usual three), because of the very small moment

of inertia of such molecules along the line of centers of the atoms.

to the molar specific heat. There is one proviso, however.

Linear molecules (like hydrogen chloride) effectively only have two rotational degrees of

freedom (instead of the usual three), because of the very small moment

of inertia of such molecules along the line of centers of the atoms.

![\includegraphics[width=0.85\textwidth]{Chapter06/h2.eps}](img4215.png) |

Figure 5.5 shows the variation of the molar heat capacity at constant volume

of gaseous molecular hydrogen (i.e.,  ) with temperature. The expected contribution

from the translational degrees of freedom is

) with temperature. The expected contribution

from the translational degrees of freedom is  (there are

three translational degrees of freedom per molecule). The

expected contribution at

high temperatures from the rotational degrees of freedom is

(there are

three translational degrees of freedom per molecule). The

expected contribution at

high temperatures from the rotational degrees of freedom is  (there are effectively

two rotational degrees of freedom per molecule). Finally, the expected contribution at high temperatures from the vibrational degrees of freedom is

(there are effectively

two rotational degrees of freedom per molecule). Finally, the expected contribution at high temperatures from the vibrational degrees of freedom is  (there

is one vibrational degree of freedom per molecule). It can be seen that,

as the temperature rises, the rotational, and then the vibrational, degrees

of freedom eventually make their full classical contributions to the heat

capacity.

(there

is one vibrational degree of freedom per molecule). It can be seen that,

as the temperature rises, the rotational, and then the vibrational, degrees

of freedom eventually make their full classical contributions to the heat

capacity.