Next: Applications of Statistical Mechanics Up: Statistical Mechanics Previous: Thermodynamic Temperature

We can think of the interaction of a molecule with the

air in a classroom as

analogous to the interaction of a small system,  , in thermal contact with a

heat reservoir,

, in thermal contact with a

heat reservoir,  . The air acts like a heat reservoir because its energy

fluctuations due to interactions

with the molecule are far too small to affect any

of its macroscopic parameters. Let us

determine the probability,

. The air acts like a heat reservoir because its energy

fluctuations due to interactions

with the molecule are far too small to affect any

of its macroscopic parameters. Let us

determine the probability,  , of finding system

, of finding system  in one particular

internal state,

in one particular

internal state,  , of energy

, of energy

, when it is thermal equilibrium with the heat

reservoir,

, when it is thermal equilibrium with the heat

reservoir,  .

.

As usual, we assume fairly weak interaction between  and

and  , so that

the energies of these two systems

are additive. The energy of

, so that

the energies of these two systems

are additive. The energy of  is not known at this

stage. In fact, only the total internal energy of the combined system,

is not known at this

stage. In fact, only the total internal energy of the combined system,

, is known. Suppose that the

total internal energy lies in the range

, is known. Suppose that the

total internal energy lies in the range  to

to

.

The overall internal energy is constant in time, because

.

The overall internal energy is constant in time, because  is assumed to be an isolated system, so

is assumed to be an isolated system, so

|

(5.321) |

denotes the internal energy of the reservoir

denotes the internal energy of the reservoir  . Let

. Let

be the

number of accessible states of the reservoir when its internal energy lies in the

range

be the

number of accessible states of the reservoir when its internal energy lies in the

range  to

to

. Clearly, if system

. Clearly, if system  has an energy

has an energy

then

the reservoir

then

the reservoir  must have an energy close to

must have an energy close to

. Hence,

because

. Hence,

because  is in one definite state (i.e., state

is in one definite state (i.e., state  ), and the total

number of states accessible to

), and the total

number of states accessible to  is

is

, it

follows that

the total number

of states accessible to the combined system is simply

, it

follows that

the total number

of states accessible to the combined system is simply

.

The principle of equal a priori probabilities tells us the probability

of occurrence of a particular situation is proportional to the number

of accessible states. Thus,

.

The principle of equal a priori probabilities tells us the probability

of occurrence of a particular situation is proportional to the number

of accessible states. Thus,

|

(5.322) |

is a constant of proportionality that is independent of

is a constant of proportionality that is independent of  .

This constant can be determined by the normalization condition

where the sum is over all possible states of system

.

This constant can be determined by the normalization condition

where the sum is over all possible states of system  , irrespective of their energy. [See Equation (5.3).]

, irrespective of their energy. [See Equation (5.3).]

Let us now make use of the fact that system  is far smaller than system

is far smaller than system  .

It follows that

.

It follows that

, so the slowly-varying logarithm of

, so the slowly-varying logarithm of  can be Taylor expanded about

can be Taylor expanded about

. Thus,

. Thus,

, rather than

, rather than  itself, because the latter

function varies so rapidly with energy

that the radius of convergence of its Taylor series

is too small for the series to be of any practical use.

The higher-order terms in Equation (5.324) can be safely

neglected, because

itself, because the latter

function varies so rapidly with energy

that the radius of convergence of its Taylor series

is too small for the series to be of any practical use.

The higher-order terms in Equation (5.324) can be safely

neglected, because

. Now, the derivative

. Now, the derivative

![$\displaystyle \left[\frac{\partial \ln {\mit\Omega}'}{\partial U'} \right]_0 \equiv \beta$](img4018.png) |

(5.325) |

, and is, thus, a constant, independent

of the energy,

, and is, thus, a constant, independent

of the energy,

, of

, of  . In fact, we know, from the previous section, that this derivative

is just the

temperature parameter

. In fact, we know, from the previous section, that this derivative

is just the

temperature parameter

characterizing the heat

reservoir

characterizing the heat

reservoir  . Here,

. Here,  is the absolute temperature of the reservoir. Hence, Equation (5.324) becomes

is the absolute temperature of the reservoir. Hence, Equation (5.324) becomes

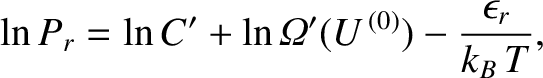

|

(5.326) |

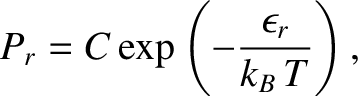

|

(5.327) |

is a constant independent of

is a constant independent of  . The parameter

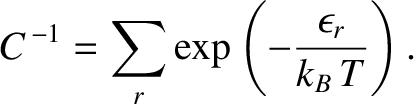

. The parameter  is determined by

the normalization condition, (5.323), which gives

is determined by

the normalization condition, (5.323), which gives

|

(5.328) |

We conclude that the probability of a measurement of the energy of some system  , that is in thermal

equilibrium with a heat reservoir of temperature

, that is in thermal

equilibrium with a heat reservoir of temperature  , yielding the result

, yielding the result

is

is