Next: Fine Structure of Hydrogen

Up: Relativistic Electron Theory

Previous: Electron Spin

To further study the motion of an electron in a central field, whose Hamiltonian is

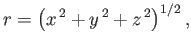

it is convenient to transform to polar coordinates. Let

|

(11.129) |

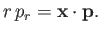

and

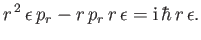

|

(11.130) |

It is easily demonstrated that

![$\displaystyle [r,p_r] = {\rm i} \,\hbar,$](img4045.png) |

(11.131) |

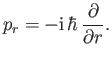

which implies that in the Schrödinger representation

|

(11.132) |

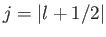

Now, by symmetry, an energy eigenstate in a central field is a simultaneous eigenstate of the total angular momentum

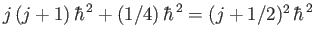

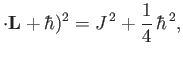

Furthermore, we know from general principles that the eigenvalues of  are

are

, where

, where  is a positive half-integer (because

is a positive half-integer (because

, where

, where  is the standard non-negative integer quantum number associated with orbital angular momentum.)

(See Chapter 6.)

is the standard non-negative integer quantum number associated with orbital angular momentum.)

(See Chapter 6.)

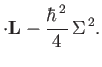

It follows from Equation (11.101) that

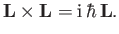

However, because  is an angular momentum, its components satisfy the standard commutation relations

is an angular momentum, its components satisfy the standard commutation relations

|

(11.135) |

(See Section 4.1.)

Thus, we obtain

However,

, so

, so

Further application of Equation (11.101) yields

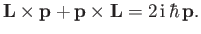

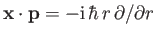

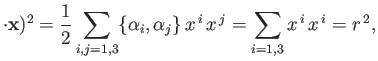

However, it is easily demonstrated from the fundamental commutation relations between position and momentum operators that

|

(11.140) |

(See Section 2.2.)

Thus,

which implies that

Now,

. Moreover,

. Moreover,

commutes with

commutes with  ,

,  , and

, and

. Hence,

we conclude that

. Hence,

we conclude that

Finally, because  commutes with

commutes with  and

and  , but anti-commutes with the components of

, but anti-commutes with the components of

, we obtain

, we obtain

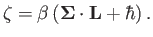

where

|

(11.145) |

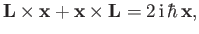

If we repeat the previous analysis, starting at Equation (11.138), but substituting  for

for  , and

making use of the easily demonstrated result

, and

making use of the easily demonstrated result

|

(11.146) |

we find that

Now,  commutes with

commutes with  , as well as the components of

, as well as the components of

and

and  . Hence,

. Hence,

![$\displaystyle [\zeta,r] = 0.$](img4081.png) |

(11.148) |

Moreover,  commutes with the components of

commutes with the components of  , and can easily be shown to commute with all

of the components of

, and can easily be shown to commute with all

of the components of

.

It follows that

.

It follows that

![$\displaystyle [\zeta,\beta]=0.$](img4082.png) |

(11.149) |

Hence, Equations (11.128), (11.144), (11.148), and (11.149) imply that

![$\displaystyle [\zeta, H] =0.$](img4083.png) |

(11.150) |

In other words, an eigenstate of the Hamiltonian is a simultaneous eigenstate of  .

Now,

.

Now,

where use has been made of Equation (11.137), as well as

. It follows that the eigenvalues of

. It follows that the eigenvalues of

are

are

. Thus, the eigenvalues of

. Thus, the eigenvalues of  can be written

can be written  , where

, where

is a non-zero integer.

is a non-zero integer.

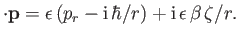

Equation (11.101) implies that

where use has been made of Equations (11.130) and (11.145).

It is helpful to define the dimensionless operator  , where

, where

Moreover, it is evident that

![$\displaystyle [\epsilon,r] = 0.$](img4100.png) |

(11.154) |

Hence,

where use has been made of Equation (11.24).

It follows that

|

(11.156) |

We have already seen that  commutes with

commutes with

and

and  . Thus,

. Thus,

![$\displaystyle [\zeta,\epsilon] = 0.$](img4105.png) |

(11.157) |

Because

commutes with

commutes with  and

and  , and

, and

, as well

as

, as well

as

, we obtain

, we obtain

However,

and

and

, so, multiplying through by

, so, multiplying through by

, we get

, we get

|

(11.159) |

Equation (11.131) then yields

![$\displaystyle [\epsilon,p_r]= 0.$](img4114.png) |

(11.160) |

Equation (11.152) implies that

Making use of Equations (11.148), (11.153), (11.154), and (11.156), we get

|

(11.162) |

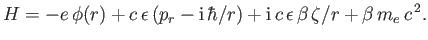

Hence, the Hamiltonian (11.128) becomes

|

(11.163) |

Now, we wish to solve the energy eigenvalue problem

|

(11.164) |

where  is the energy eigenvalue. However, we have already shown that an eigenstate of the Hamiltonian is a simultaneous eigenstate of the

is the energy eigenvalue. However, we have already shown that an eigenstate of the Hamiltonian is a simultaneous eigenstate of the  operator belonging to the eigenvalue

operator belonging to the eigenvalue  , where

, where  is a non-zero integer. Hence, the eigenvalue problem reduces to

is a non-zero integer. Hence, the eigenvalue problem reduces to

![$\displaystyle \left[- e\,\phi(r) + c\,\epsilon\,(p_r-{\rm i}\,\hbar/r) + {\rm i}\,c\,\hbar\,k\,\epsilon\,\beta/r + \beta\,m_e\,c^{\,2}\right]\psi = E\,\psi,$](img4118.png) |

(11.165) |

which only involves the radial coordinate,  . It is easily demonstrated that

. It is easily demonstrated that  anti-commutes with

anti-commutes with  . Hence, given that

. Hence, given that

takes the form (11.32), and that

takes the form (11.32), and that

, we can represent

, we can represent  as the matrix

as the matrix

![$\displaystyle \epsilon = \left(\begin{array}{rr}0,&-{\rm i}\\ [0.5ex]{\rm i},&0\end{array}\right).$](img4120.png) |

(11.166) |

Thus, writing  in the spinor form

in the spinor form

![$\displaystyle \psi = \left(\begin{array}{c} \psi_a(r)\\ [0.5ex]\psi_b(r)\end{array}\right),$](img4121.png) |

(11.167) |

and making use of Equation (11.132),

the energy eigenvalue problem for an electron in a central field reduces to the following two coupled radial differential equations:

Next: Fine Structure of Hydrogen

Up: Relativistic Electron Theory

Previous: Electron Spin

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-22

![]() for

for ![]() , and

making use of the easily demonstrated result

, and

making use of the easily demonstrated result

![]() commutes with

commutes with ![]() , as well as the components of

, as well as the components of

![]() and

and ![]() . Hence,

. Hence,

![]() , where

, where

![]() commutes with

commutes with ![]() and

and ![]() , and

, and

![]() , as well

as

, as well

as

![]() , we obtain

, we obtain

![$\displaystyle \epsilon = \left(\begin{array}{rr}0,&-{\rm i}\\ [0.5ex]{\rm i},&0\end{array}\right).$](img4120.png)

![$\displaystyle \psi = \left(\begin{array}{c} \psi_a(r)\\ [0.5ex]\psi_b(r)\end{array}\right),$](img4121.png)