Next: Motion in Central Field

Up: Relativistic Electron Theory

Previous: Free Electron Motion

Electron Spin

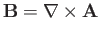

According to Equation (11.39), the relativistic Hamiltonian of an electron in an electromagnetic

field is

Hence,

![$\displaystyle \left(\frac{H}{c}+\frac{e}{c}\,\phi\right)^2 = \left[\mbox{\boldm...

...{\boldmath$\alpha$}\cdot({\bf p}+e\,{\bf A})\right]^{\,2} + m_e^{\,2}\,c^{\,2},$](img3988.png) |

(11.95) |

where use has been made of Equations (11.25) and (11.26).

Now, we can write

|

(11.96) |

for  , where

, where

![$\displaystyle \gamma^{\,5} = \left(\begin{array}{cc} 0,& 1\\ [0.5ex]1, & 0\end{array}\right),$](img3990.png) |

(11.97) |

and

![$\displaystyle \Sigma_{\,i} = \left(\begin{array}{cc} \sigma_i,& 0\\ [0.5ex]0,& \sigma_i\end{array}\right).$](img3991.png) |

(11.98) |

Here, 0

and  denote

denote  null and identity matrices, respectively, whereas the

null and identity matrices, respectively, whereas the  are conventional

are conventional

Pauli matrices. Note that

Pauli matrices. Note that

, and

, and

![$\displaystyle [\gamma^{\,5}, \Sigma_{\,i}]=0.$](img3993.png) |

(11.99) |

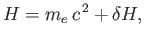

It follows from Equation (11.95) that

![$\displaystyle \left(\frac{H}{c}+\frac{e}{c}\,\phi\right)^2 = \left[\mbox{\boldmath$\Sigma$}\cdot({\bf p}+e\,{\bf A})\right]^{\,2} + m_e^{\,2}\,c^{\,2}.$](img3994.png) |

(11.100) |

Now, a straightforward generalization of Equation (5.93) gives

where  and

and  are any two three-dimensional vectors that commute with

are any two three-dimensional vectors that commute with

.

It follows that

.

It follows that

![$\displaystyle \left[\mbox{\boldmath$\Sigma$}\cdot({\bf p}+e\,{\bf A})\right]^{\...

...,\mbox{\boldmath$\Sigma$}\cdot ({\bf p}+e\,{\bf A})\times ({\bf p}+e\,{\bf A}).$](img4000.png) |

(11.102) |

However,

where

is the magnetic field-strength.

Hence, we obtain

is the magnetic field-strength.

Hence, we obtain

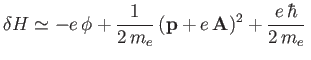

Consider the non-relativistic limit. In this case, we can write

|

(11.105) |

where  is small compared to

is small compared to

. Substituting into Equation (11.104), and neglecting

. Substituting into Equation (11.104), and neglecting

, and other

terms involving

, and other

terms involving  , we get

, we get

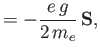

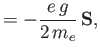

This Hamiltonian is the same as the classical Hamiltonian of a non-relativistic electron, except for the final term. (See Section 3.6.)

This term may be interpreted as arising from the electron having an intrinsic magnetic moment

(See Section 5.6.)

In order to demonstrate that the electron's intrinsic magnetic moment is associated with an intrinsic angular momentum,

consider the motion of an electron in a central electrostatic potential: that is,

and

and

.

In this case, the Hamiltonian (11.94) becomes

.

In this case, the Hamiltonian (11.94) becomes

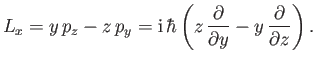

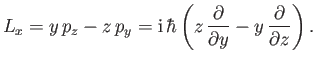

Consider the  -component of the electron's orbital angular momentum,

-component of the electron's orbital angular momentum,

|

(11.109) |

The Heisenberg equation of motion for this quantity is

![$\displaystyle {\rm i}\,\hbar\,\dot{L}_x = [L_x,H].$](img4017.png) |

(11.110) |

However, it is easily demonstrated that

![$\displaystyle [L_x,r]$](img4018.png) |

|

(11.111) |

![$\displaystyle [L_x,p_x]$](img4019.png) |

|

(11.112) |

![$\displaystyle [L_x,p_y]$](img4020.png) |

|

(11.113) |

![$\displaystyle [L_x,p_z]$](img4022.png) |

|

(11.114) |

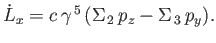

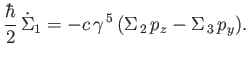

Hence, we obtain

![$\displaystyle [L_x,H] = {\rm i}\,\hbar\,c\,\gamma^{\,5}\,(\Sigma_{\,2}\,p_z-\Sigma_{\,3}\,p_y),$](img4024.png) |

(11.115) |

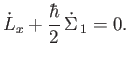

which implies that

|

(11.116) |

It can be seen that  is not a constant of the motion. However, the

is not a constant of the motion. However, the  -component of the total angular

momentum of the system must be a constant of the motion (because a central electrostatic potential exerts zero torque on the system). Hence, we deduce that the electron possesses additional

angular momentum that is not connected with its motion through space. Now,

-component of the total angular

momentum of the system must be a constant of the motion (because a central electrostatic potential exerts zero torque on the system). Hence, we deduce that the electron possesses additional

angular momentum that is not connected with its motion through space. Now,

![$\displaystyle {\rm i}\,\hbar\,\dot{\Sigma}_{\,1}= [\Sigma_{\,1},H].$](img4026.png) |

(11.117) |

However,

![$\displaystyle [\Sigma_{\,1},\beta]$](img4027.png) |

|

(11.118) |

![$\displaystyle [\Sigma_{\,1},\gamma^{\,5}]$](img4028.png) |

|

(11.119) |

![$\displaystyle [\Sigma_{\,1},\Sigma_{\,1}]$](img4029.png) |

|

(11.120) |

![$\displaystyle [\Sigma_{\,1},\Sigma_{\,2}]$](img4030.png) |

|

(11.121) |

![$\displaystyle [\Sigma_{\,1},\Sigma_{\,3}]$](img4032.png) |

|

(11.122) |

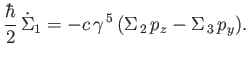

so

![$\displaystyle [\Sigma_{\,1},H] = 2\,{\rm i}\,c\,\gamma^{\,5}\,(\Sigma_{\,3}\,p_y-\Sigma_{\,2}\,p_z),$](img4034.png) |

(11.123) |

which implies that

|

(11.124) |

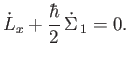

Hence, we deduce that

|

(11.125) |

Because there is nothing special about the  -direction, we conclude that the vector

-direction, we conclude that the vector

is

a constant of the motion. We can interpret this result by saying that the electron has a spin angular momentum

is

a constant of the motion. We can interpret this result by saying that the electron has a spin angular momentum

, which must be added to its orbital angular momentum in order to obtain a constant of the motion.

According to Equation (11.107), the relationship between the electron's spin angular momentum and its intrinsic (i.e., non-orbital) magnetic moment is

, which must be added to its orbital angular momentum in order to obtain a constant of the motion.

According to Equation (11.107), the relationship between the electron's spin angular momentum and its intrinsic (i.e., non-orbital) magnetic moment is

|

(11.126) |

where the gyromagnetic ratio,  , takes the value

, takes the value

|

(11.127) |

As explained in Section 5.5, this is twice the value one would naively predict by analogy with classical physics.

Next: Motion in Central Field

Up: Relativistic Electron Theory

Previous: Free Electron Motion

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-22

![$\displaystyle \gamma^{\,5} = \left(\begin{array}{cc} 0,& 1\\ [0.5ex]1, & 0\end{array}\right),$](img3990.png)

![$\displaystyle \left(\frac{H}{c}+\frac{e}{c}\,\phi\right)^2 = \left[\mbox{\boldmath$\Sigma$}\cdot({\bf p}+e\,{\bf A})\right]^{\,2} + m_e^{\,2}\,c^{\,2}.$](img3994.png)

![]() and

and

![]() .

In this case, the Hamiltonian (11.94) becomes

.

In this case, the Hamiltonian (11.94) becomes