Next: Eigenvalues of Orbital Angular

Up: Orbital Angular Momentum

Previous: Orbital Angular Momentum

Orbital Angular Momentum

Consider a particle described by the Cartesian coordinates

and their conjugate momenta

and their conjugate momenta

. The classical

definition of the orbital angular momentum of such a particle about the

origin is

. The classical

definition of the orbital angular momentum of such a particle about the

origin is

[55], giving

[55], giving

Let us assume that the operators

that

represent the components of

orbital angular momentum in quantum mechanics can be defined in

an analogous manner to the corresponding components of

classical angular momentum. In other words, we are

going to assume that the previous equations specify the angular momentum operators

in terms of the position and linear momentum operators. According to Equations (4.1)-(4.3),

that

represent the components of

orbital angular momentum in quantum mechanics can be defined in

an analogous manner to the corresponding components of

classical angular momentum. In other words, we are

going to assume that the previous equations specify the angular momentum operators

in terms of the position and linear momentum operators. According to Equations (4.1)-(4.3),  ,

,  ,

and

,

and  are Hermitian operators, so they represent quantities that can, in principle,

be measured. Note, incidentally, that there is no ambiguity regarding the order

in which operators appear in products on the right-hand sides of Equations (4.1)-(4.3),

because all of the products consist of operators that commute.

are Hermitian operators, so they represent quantities that can, in principle,

be measured. Note, incidentally, that there is no ambiguity regarding the order

in which operators appear in products on the right-hand sides of Equations (4.1)-(4.3),

because all of the products consist of operators that commute.

The fundamental commutation relations satisfied by the

position and linear momentum operators are

where  and

and  stand for either

stand for either  ,

,  , or

, or  . [See Equations (2.23)-(2.25).]

Consider the commutator of the operators

. [See Equations (2.23)-(2.25).]

Consider the commutator of the operators  and

and  :

:

The cyclic permutations (i.e.,

, etc.) of the previous result yield

the fundamental commutation relations satisfied

by the components of an orbital angular momentum:

, etc.) of the previous result yield

the fundamental commutation relations satisfied

by the components of an orbital angular momentum:

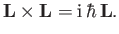

These expressions can be summed up more succinctly by writing

|

(4.11) |

The three commutation relations (4.8)-(4.10) are the foundation for the whole

theory of angular momentum in quantum mechanics. Whenever we encounter

three operators having similar commutation relations, we know the

dynamical variables that they represent have identical properties

to those of the components of an

angular momentum (which we are about to derive). In fact,

we shall assume that any three operators that satisfy the commutation

relations (4.8)-(4.10) represent the components of some sort of angular momentum.

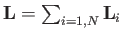

Suppose that there are  particles in the system, with

angular momentum vectors

particles in the system, with

angular momentum vectors  (where

(where  runs from 1 to

runs from 1 to  ).

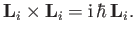

Each of these vectors satisfies Equation (4.11), so that

).

Each of these vectors satisfies Equation (4.11), so that

|

(4.12) |

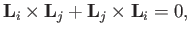

However, we expect the angular momentum operators

belonging to different particles to commute, because they represent different

degrees of freedom of the system. (See Section 2.2.) So,

we can write

|

(4.13) |

for  . Consider the total angular momentum of the system,

. Consider the total angular momentum of the system,

. It is clear from Equations (4.12) and (4.13)

that

. It is clear from Equations (4.12) and (4.13)

that

Thus, the sum of two or more angular momentum vectors satisfies the

same commutation relation as a primitive angular momentum vector.

In particular, the total angular momentum of the system satisfies the

commutation relation (4.11).

The immediate conclusion that can be drawn from the commutation relations

(4.8)-(4.10) is that the three components of an angular momentum vector cannot

be specified (or measured) simultaneously. In fact, once we have specified one

component, the values of other two components become uncertain. It is

conventional to specify the  -component,

-component,  .

.

Consider the magnitude squared of the angular momentum vector,

. The commutator of

. The commutator of  and

and  is

written

is

written

![$\displaystyle [L^2, L_z] = [L_x^{\,2}, L_z] + [L_y^{\,2}, L_z] + [L_z^{\,2}, L_z].$](img960.png) |

(4.15) |

It is easily demonstrated that

which implies that

![$\displaystyle [L^2, L_z] = 0.$](img966.png) |

(4.19) |

(See Exercise 1.)

Because there is nothing special about the  -direction, we conclude that

-direction, we conclude that  also

commutes with

also

commutes with  and

and  . It is clear from Equations (4.8)-(4.10) and

(4.19) that the best we

can do in quantum mechanics is to specify the

magnitude of an angular momentum vector

along with one of its components (by convention, the

. It is clear from Equations (4.8)-(4.10) and

(4.19) that the best we

can do in quantum mechanics is to specify the

magnitude of an angular momentum vector

along with one of its components (by convention, the  -component).

-component).

It is convenient to define the ladder operators,  and

and  :

:

It can easily be shown that

and also that both ladder operators commute with  . (See Exercise 1.)

. (See Exercise 1.)

Next: Eigenvalues of Orbital Angular

Up: Orbital Angular Momentum

Previous: Orbital Angular Momentum

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-22

![]() particles in the system, with

angular momentum vectors

particles in the system, with

angular momentum vectors ![]() (where

(where ![]() runs from 1 to

runs from 1 to ![]() ).

Each of these vectors satisfies Equation (4.11), so that

).

Each of these vectors satisfies Equation (4.11), so that

![]() -component,

-component, ![]() .

.

![]() . The commutator of

. The commutator of ![]() and

and ![]() is

written

is

written

![]() and

and ![]() :

: