Next: Exercises Up: Magnetohydrodynamic Fluids Previous: Perpendicular MHD Shocks Contents

, or

In other words, it is convenient to transform to a frame that moves at the local

, or

In other words, it is convenient to transform to a frame that moves at the local

velocity of the plasma.

It immediately follows from the jump condition (8.181) that

or

velocity of the plasma.

It immediately follows from the jump condition (8.181) that

or

. Thus, in the de Hoffmann-Teller frame, the upstream plasma

flow is parallel to the upstream magnetic field, and the downstream plasma

flow is also parallel to the downstream magnetic field. Furthermore, the magnetic contribution to the jump

condition (8.185) becomes identically zero, which is a considerable simplification.

. Thus, in the de Hoffmann-Teller frame, the upstream plasma

flow is parallel to the upstream magnetic field, and the downstream plasma

flow is also parallel to the downstream magnetic field. Furthermore, the magnetic contribution to the jump

condition (8.185) becomes identically zero, which is a considerable simplification.

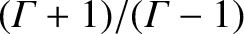

Equations (8.208) and (8.209) can be combined with the general jump conditions (8.180)–(8.185) to give

where is the component of the upstream velocity normal to the

shock front,

and

is the component of the upstream velocity normal to the

shock front,

and  is the angle subtended between the upstream plasma flow and the

shock front normal. Finally, given the compression ratio,

is the angle subtended between the upstream plasma flow and the

shock front normal. Finally, given the compression ratio,  , the square of the normal

upstream velocity,

, the square of the normal

upstream velocity,  , is a real root of a cubic equation

known as the shock adiabatic:

, is a real root of a cubic equation

known as the shock adiabatic:

| 0 | ![$\displaystyle =(v_{1}^{2}-r\,\cos^2\theta_1\,V_{A\,1}^{2})^{2}\left(

\left[({\mit\Gamma}+1)-({\mit\Gamma}-1)\,r\right]

v_{1}^{2}- 2\,r\,V_{S\,1}^{2}\right)$](img3169.png) |

(8.216) |

![$\displaystyle \phantom{=}-r\,\sin^2\theta_1\,v_{1}^{2}\,V_{A\,1}^{2}\left(

\lef...

...mit\Gamma}+1)-({\mit\Gamma}-1)\,r\right]r\,\cos^2\theta_1\,V_{A\,1}^{2}\right).$](img3170.png) |

.

.

Let us first consider the weak shock limit

. In this case, it is easily seen that the three roots of the

shock adiabatic reduce to

. In this case, it is easily seen that the three roots of the

shock adiabatic reduce to

|

![$\displaystyle =V_{-\,1}^{2}\equiv \frac{V_{A\,1}^{2}+V_{S\,1}^{2}- [(V_{A\,1}^{2}+V_{S\,1}^{2})^{2}

-4\,\cos^2\theta_1\,V_{S\,1}^{2}\,V_{A\,1}^{2}]^{1/2}}{2},$](img3173.png) |

(8.217) |

|

|

(8.218) |

|

![$\displaystyle =V_{+\,1}^{2}\equiv \frac{V_{A\,1}^{2}+V_{S\,1}^{2} + [(V_{A\,1}^{2}+V_{S\,1}^{2})^{2}

-4\,\cos^2\theta_1\,V_{S\,1}^{2}\,V_{A\,1}^{2}]^{1/2}}{2}.$](img3175.png) |

(8.219) |

|

(8.220) |

for a fast shock,

whereas

for a fast shock,

whereas

for a slow shock. For the case of an intermediate shock, we

can show, after a little algebra, that

for a slow shock. For the case of an intermediate shock, we

can show, after a little algebra, that

in the limit

in the limit

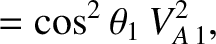

. We conclude that (in the de Hoffmann-Teller frame) fast shocks refract the magnetic field and plasma

flow (recall that they are parallel in our adopted frame of the reference) away from

the normal to the shock front, whereas slow shocks refract these quantities toward

the normal. Moreover, the tangential magnetic field and plasma flow generally reverse

across an intermediate shock front. This is illustrated in Figure 8.8.

. We conclude that (in the de Hoffmann-Teller frame) fast shocks refract the magnetic field and plasma

flow (recall that they are parallel in our adopted frame of the reference) away from

the normal to the shock front, whereas slow shocks refract these quantities toward

the normal. Moreover, the tangential magnetic field and plasma flow generally reverse

across an intermediate shock front. This is illustrated in Figure 8.8.

![\includegraphics[height=2.5in]{Chapter08/fig8_8.eps}](img3180.png) |

When  is slightly larger than unity, it is easily demonstrated that the conditions for the

existence of a slow, intermediate, and fast shock are

is slightly larger than unity, it is easily demonstrated that the conditions for the

existence of a slow, intermediate, and fast shock are

,

,

, and

, and

, respectively.

, respectively.

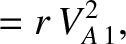

Let us now consider the strong shock limit,

. In this case, the shock

adiabatic yields

. In this case, the shock

adiabatic yields

, and

, and

![$\displaystyle v_1^{2} \simeq \frac{r_m}{{\mit\Gamma}-1}\,\frac{2\,V_{S\,1}^{2}+\sin^2\theta_1\,[{\mit\Gamma}

+ (2-{\mit\Gamma})\,r_m]\,V_{A\,1}^{2}}{r_m-r}.$](img3186.png) |

(8.221) |

by any type of MHD shock.

by any type of MHD shock.

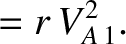

Consider the special case

in which both the plasma flow and the

magnetic field are normal to the shock front. In this case, the three roots of the shock adiabatic are

in which both the plasma flow and the

magnetic field are normal to the shock front. In this case, the three roots of the shock adiabatic are

|

|

(8.222) |

|

|

(8.223) |

|

|

(8.224) |

, and as a fast shock

when

, and as a fast shock

when

. The other two roots are identical, and correspond to

shocks that propagate at the velocity

. The other two roots are identical, and correspond to

shocks that propagate at the velocity

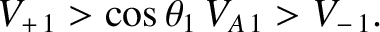

and “switch-on" the tangential

components of the plasma flow and the magnetic field: that is, it can be seen from

Equations (8.212) and (8.214) that

and “switch-on" the tangential

components of the plasma flow and the magnetic field: that is, it can be seen from

Equations (8.212) and (8.214) that

while

while

and

and

for these types of shock. Incidentally, it is also

possible to have a “switch-off” shock that eliminates the tangential components

of the plasma flow and the magnetic field. According to Equations (8.212) and (8.214),

such a shock propagates at the velocity

for these types of shock. Incidentally, it is also

possible to have a “switch-off” shock that eliminates the tangential components

of the plasma flow and the magnetic field. According to Equations (8.212) and (8.214),

such a shock propagates at the velocity

. Switch-on and

switch-off shocks are illustrated in Figure 8.9.

. Switch-on and

switch-off shocks are illustrated in Figure 8.9.

![\includegraphics[height=2.5in]{Chapter08/fig8_9.eps}](img3198.png) |

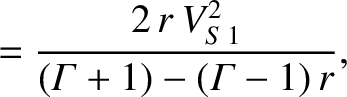

Let us, finally, consider the special case

. As is easily demonstrated, the three roots of the

shock adiabatic are

. As is easily demonstrated, the three roots of the

shock adiabatic are

|

![$\displaystyle = r \left(\frac{2\,V_{S\,1}^{2} + [{\mit\Gamma}+(2-{\mit\Gamma})\,r]\,V_{A\,1}^{2}}

{[{\mit\Gamma}+1]-[{\mit\Gamma}-1]\,r}\right)

,$](img3199.png) |

(8.225) |

|

|

(8.226) |

|

|

(8.227) |

MHD shocks have been observed in a large variety of situations. For instance, shocks are known to be formed by supernova explosions, by strong stellar winds, by solar flares, and by the solar wind upstream of planetary magnetospheres (Gurnett and Bhattacharjee 2005).