Next: Parallel MHD Shocks Up: Magnetohydrodynamic Fluids Previous: Ponomarenko Dynamo Contents

Let us investigate shocks in MHD fluids. Because information in such fluids is carried via three different waves—namely, fast, or compressional-Alfvén, waves; intermediate, or shear-Alfvén, waves; and slow, or magnetosonic, waves (see Section 8.4)—we might expect MHD fluids to support three different types of shock, corresponding to disturbances traveling faster than each of the aforementioned waves. This is indeed the case.

In general, a shock propagating through an MHD fluid produces a significant difference in plasma properties on either side of the shock front. The thickness of the front is determined by a balance between convective and dissipative effects. However, dissipative effects in high temperature plasmas are only comparable to convective effects when the spatial gradients in plasma variables become extremely large. Hence, MHD shocks in such plasmas tend to be extremely narrow, and are well approximated as discontinuous changes in plasma parameters. The MHD equations, combined with Maxwell's equations, can be integrated across a shock to give a set of jump conditions that relate plasma properties on each side of the shock front. If the shock is sufficiently narrow then these relations become independent of its detailed structure. Let us derive the jump conditions for a narrow, planar, steady-state, MHD shock.

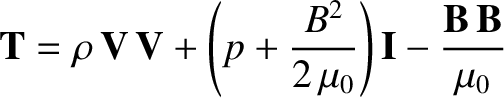

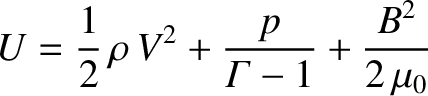

Maxwell's equations, and the MHD equations, (8.1)–(8.4), can be combined and written in the following convenient form (Boyd and Sanderson 2003):

where |

(8.174) |

the identity tensor,

the identity tensor,

|

(8.175) |

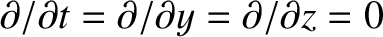

Let us transform into the rest frame of the shock. Suppose that the

shock front coincides with the  -

- plane.

Furthermore, let the regions

of the plasma upstream and downstream of the shock, which are termed

regions 1 and 2, respectively, be spatially uniform and non-time-varying. It follows

that

plane.

Furthermore, let the regions

of the plasma upstream and downstream of the shock, which are termed

regions 1 and 2, respectively, be spatially uniform and non-time-varying. It follows

that

. Moreover,

. Moreover,

, except in the immediate vicinity of the shock.

Finally, let the velocity

and magnetic fields upstream and downstream of the shock

all lie in the

, except in the immediate vicinity of the shock.

Finally, let the velocity

and magnetic fields upstream and downstream of the shock

all lie in the  -

- plane. The situation under discussion is illustrated in Figure 8.7. Here,

plane. The situation under discussion is illustrated in Figure 8.7. Here,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  are

the upstream mass density, pressure, velocity, and magnetic field,

respectively, whereas

are

the upstream mass density, pressure, velocity, and magnetic field,

respectively, whereas  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  are the corresponding downstream quantities.

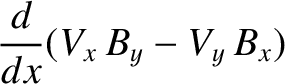

In the immediate vicinity of the shock, Equations (8.169)–(8.173) reduce to

are the corresponding downstream quantities.

In the immediate vicinity of the shock, Equations (8.169)–(8.173) reduce to

|

|

|

|

(8.177) |

|

|

|

|

(8.178) |

|

|

|

|

(8.179) |

![$[A]_1^2\equiv A_2-A_1$](img3079.png) . These relations are known as the Rankine-Hugoniot

relations for MHD (Boyd and Sanderson 2003).

Assuming that all of the upstream plasma parameters

are known, there are six unknown parameters in the problem—namely,

. These relations are known as the Rankine-Hugoniot

relations for MHD (Boyd and Sanderson 2003).

Assuming that all of the upstream plasma parameters

are known, there are six unknown parameters in the problem—namely,

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  . These six

unknowns are fully determined by the six jump conditions. Unfortunately, the

general case is very complicated. So, before tackling it, let us examine

a couple of relatively simple special cases.

. These six

unknowns are fully determined by the six jump conditions. Unfortunately, the

general case is very complicated. So, before tackling it, let us examine

a couple of relatively simple special cases.