Next: Bernoulli's Theorem

Up: One-Dimensional Compressible Inviscid Flow

Previous: Isentropic Flow

Sound Waves

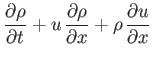

Suppose

that

,

,

,

,  , and

, and

in Equations (14.30) and (14.31).

We obtain

in Equations (14.30) and (14.31).

We obtain

Equation (14.32) implies that the flow is isentropic. In other words,

along streamlines.

Thus, it follows that

along streamlines.

Thus, it follows that

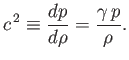

|

(14.36) |

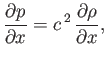

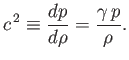

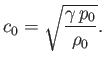

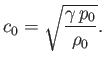

where

|

(14.37) |

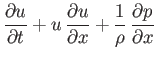

Hence, Equations (14.34) and (14.35) become

Unfortunately, these equations are difficult to solve exactly, because of the presence of nonlinear terms such as

. (See Example ix.)

. (See Example ix.)

Let us write

,

,

, and

, and

, where quantities

with the subscript

, where quantities

with the subscript  are assumed to be much smaller that corresponding quantities with the subscript 0

. Thus, we are now

considering the evolution of small-amplitude pressure and density perturbations in a stationary gas of uniform density and

pressure

are assumed to be much smaller that corresponding quantities with the subscript 0

. Thus, we are now

considering the evolution of small-amplitude pressure and density perturbations in a stationary gas of uniform density and

pressure  and

and  , respectively. To first order in small quantities, the previous two equations yield

, respectively. To first order in small quantities, the previous two equations yield

where

|

(14.42) |

The general solution to Equations (14.40) and (14.41) is well known (Fitzpatrick 2013):

where  is an arbitrary function. According to this solution, a small-amplitude density perturbation of arbitrary shape

propagates through the gas, either in the positive or negative

is an arbitrary function. According to this solution, a small-amplitude density perturbation of arbitrary shape

propagates through the gas, either in the positive or negative  -direction (corresponding to the upper and lower signs, respectively), without changing shape, at the constant speed

-direction (corresponding to the upper and lower signs, respectively), without changing shape, at the constant speed  . This type of perturbation is

known as a sound wave, and

. This type of perturbation is

known as a sound wave, and  is consequently referred to as the sound speed.

is consequently referred to as the sound speed.

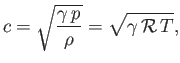

It is clear, from the previous analysis, that the general expression for the local sound speed in an isentropic ideal gas of pressure  , density

, density  , and temperature

, and temperature  , is

, is

|

(14.45) |

where use has been made of Equation (14.1).

It follows that the speed of sound is solely determined by the temperature of an ideal gas.

Let us now consider the effect of finite wave amplitude on the propagation of a sound wave through an

isentropic ideal gas. The previous analysis suggest that, in a frame of reference moving with the local flow velocity,  , a sound wave propagates at the speed

, a sound wave propagates at the speed

.

Thus, the net wave propagation speed is

.

Thus, the net wave propagation speed is

|

(14.46) |

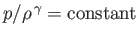

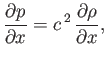

Using the isentropic law,

, to eliminate

, to eliminate  from

from

, we deduce that

, we deduce that

|

(14.47) |

Now, Equations (14.43) and (14.44) suggest that, in the presence of a sound wave propagating in the  -direction, the general differential relationship between the local flow velocity and the

density is

-direction, the general differential relationship between the local flow velocity and the

density is

|

(14.48) |

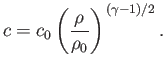

Making use of Equation (14.47), we can integrate the previous expression to give

![$\displaystyle u=\int_{\rho_0}^\rho c\,\frac{d\rho}{\rho} =\frac{2\,c_0}{\gamma-...

...ac{\rho}{\rho_0}\right)^{\,(\gamma-1)/2}-1\right]= \frac{2}{\gamma-1}\,(c-c_0),$](img5369.png) |

(14.49) |

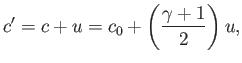

or

|

(14.50) |

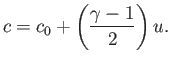

It follows that

|

(14.51) |

or

![$\displaystyle c' =c_0\left\{1+\left(\frac{\gamma+1}{\gamma-1}\right)\left[\left(\frac{\rho}{\rho_0}\right)^{\,(\gamma-1)/2}-1\right]\right\}.$](img5372.png) |

(14.52) |

Thus, we conclude that the net wave propagation speed is higher than  in regions of compression (i.e.,

in regions of compression (i.e.,

), and

lower in regions of rarefaction (i.e.,

), and

lower in regions of rarefaction (i.e.,

). This implies that a finite-amplitude sound wave distorts, as it

propagates, in such a manner that the regions of compression tend to catch up with the regions of rarefaction, leading to a

monotonic increase in time of the velocity and temperature gradients in the former regions, and a monotonic decrease in the

latter regions. Eventually, the velocity and temperature gradients in the regions of compression become so

large that it is no longer valid to neglect the effects of viscosity and heat conduction, leading to a local breakdown of the

isentropic gas law. Viscosity and heat conduction prevent any further steepening of the velocity and temperature

gradients in the regions of compression, and the wave subsequently propagates without additional distortion. However, it has now effectively been transformed into a shock wave. (See Section 14.8.)

). This implies that a finite-amplitude sound wave distorts, as it

propagates, in such a manner that the regions of compression tend to catch up with the regions of rarefaction, leading to a

monotonic increase in time of the velocity and temperature gradients in the former regions, and a monotonic decrease in the

latter regions. Eventually, the velocity and temperature gradients in the regions of compression become so

large that it is no longer valid to neglect the effects of viscosity and heat conduction, leading to a local breakdown of the

isentropic gas law. Viscosity and heat conduction prevent any further steepening of the velocity and temperature

gradients in the regions of compression, and the wave subsequently propagates without additional distortion. However, it has now effectively been transformed into a shock wave. (See Section 14.8.)

It is clear, from the previous discussion, that, at finite amplitude, there is an important difference in the behavior of compression and

rarefaction waves propagating through a gas. A compression wave tends to steepen (i.e., the temperature and velocity gradients tend to increase), and eventually becomes a shock wave, in which case it

is no longer isentropic. A rarefaction wave, on the other hand, always remains isentropic, because it tends to

flatten, thereby, further reducing the velocity and temperature gradients. Hence, there are no rarefaction, or

expansion, shocks.

Next: Bernoulli's Theorem

Up: One-Dimensional Compressible Inviscid Flow

Previous: Isentropic Flow

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-03-31

![]() ,

,

![]() , and

, and

![]() , where quantities

with the subscript

, where quantities

with the subscript ![]() are assumed to be much smaller that corresponding quantities with the subscript 0

. Thus, we are now

considering the evolution of small-amplitude pressure and density perturbations in a stationary gas of uniform density and

pressure

are assumed to be much smaller that corresponding quantities with the subscript 0

. Thus, we are now

considering the evolution of small-amplitude pressure and density perturbations in a stationary gas of uniform density and

pressure ![]() and

and ![]() , respectively. To first order in small quantities, the previous two equations yield

, respectively. To first order in small quantities, the previous two equations yield

![]() , density

, density ![]() , and temperature

, and temperature ![]() , is

, is

![]() , a sound wave propagates at the speed

, a sound wave propagates at the speed

![]() .

Thus, the net wave propagation speed is

.

Thus, the net wave propagation speed is

![$\displaystyle u=\int_{\rho_0}^\rho c\,\frac{d\rho}{\rho} =\frac{2\,c_0}{\gamma-...

...ac{\rho}{\rho_0}\right)^{\,(\gamma-1)/2}-1\right]= \frac{2}{\gamma-1}\,(c-c_0),$](img5369.png)

![$\displaystyle c' =c_0\left\{1+\left(\frac{\gamma+1}{\gamma-1}\right)\left[\left(\frac{\rho}{\rho_0}\right)^{\,(\gamma-1)/2}-1\right]\right\}.$](img5372.png)