Next: Exercises

Up: Incompressible Boundary Layers

Previous: Criterion for Boundary Layer

Approximate Solutions of Boundary Layer Equations

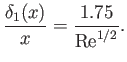

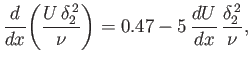

The boundary layer equations, (8.110)-(8.113), take the form

subject to the boundary conditions

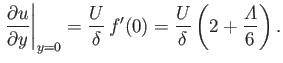

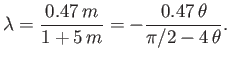

Furthermore, it follows from Equations (8.140), (8.142), and (8.143) that

|

(8.144) |

The previous expression can be thought of as an alternative form of Equation (8.143).

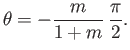

As we saw in Section 8.4, the boundary layer equations can be solved exactly when  takes the special form

takes the special form

.

However, in the general case, we must resort to approximation methods.

.

However, in the general case, we must resort to approximation methods.

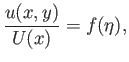

Following Pohlhausen (Schlichting 1987), let us assume that

|

(8.145) |

where

, and

, and

.

In particular, suppose that

.

In particular, suppose that

![$\displaystyle f(\eta)=\left\{\begin{array}{lcl} a+b\,\eta+c\,\eta^{\,2}+d\,\eta...

...\,4}&\mbox{\hspace{1cm}}&0\leq\eta\leq 1\\ [0.5ex] 1&&\eta>1\end{array}\right.,$](img3155.png) |

(8.146) |

where  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  are constants. This expression automatically satisfies the boundary condition (8.141).

Moreover, the boundary conditions (8.142) and (8.144) imply that

are constants. This expression automatically satisfies the boundary condition (8.141).

Moreover, the boundary conditions (8.142) and (8.144) imply that  , and

, and

|

(8.147) |

where

, and

, and

|

(8.148) |

Finally, let us assume that  ,

,  , and

, and  are continuous at

are continuous at  : that is,

: that is,

These constraints corresponds to the reasonable requirements that the

velocity, vorticity, and viscous stress tensor, respectively, be continuous across the layer.

Given that  , Equations (8.146), (8.147), and (8.149)-(8.151) yield

, Equations (8.146), (8.147), and (8.149)-(8.151) yield

|

(8.152) |

for

,

where

,

where

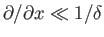

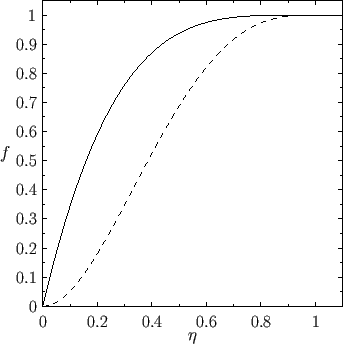

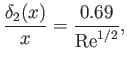

Thus, the tangential velocity profile across the layer is a function of a single parameter,

, which is

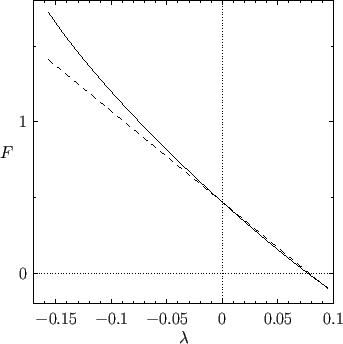

termed the Pohlhausen parameter. The behavior of this profile is illustrated in Figure 8.13. Note that, under normal

circumstances,

the Pohlhausen parameter must lie in the range

, which is

termed the Pohlhausen parameter. The behavior of this profile is illustrated in Figure 8.13. Note that, under normal

circumstances,

the Pohlhausen parameter must lie in the range

. For

. For

, the

profile is such that

, the

profile is such that  for some

for some  , which is not possible in a steady-state solution. On the

other hand, for

, which is not possible in a steady-state solution. On the

other hand, for

, the profile is such that

, the profile is such that  , which implies flow reversal close to the wall.

As we have seen, flow reversal is indicative of separation. Indeed, the separation

point,

, which implies flow reversal close to the wall.

As we have seen, flow reversal is indicative of separation. Indeed, the separation

point,  , corresponds to

, corresponds to

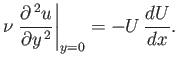

. Expression (8.152) is only an approximation, because

it satisfies some, but not all, of the boundary conditions satisfied by the true velocity profile. For instance, differentiation

of Equation (8.140) with respect to

. Expression (8.152) is only an approximation, because

it satisfies some, but not all, of the boundary conditions satisfied by the true velocity profile. For instance, differentiation

of Equation (8.140) with respect to  reveals that

reveals that

, which is not the case for expression (8.152).

, which is not the case for expression (8.152).

Figure:

Pohlhausen velocity profiles for

(solid curve) and

(solid curve) and

(dashed curve).

(dashed curve).

|

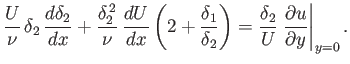

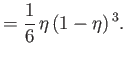

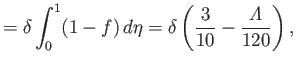

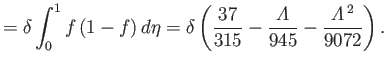

It follows from Equations (8.115), (8.116), and (8.152)-(8.154) that

Furthermore,

|

(8.157) |

The von Kármán momentum integral, (8.117), can be rearranged to give

|

(8.158) |

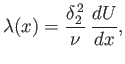

Defining

|

(8.159) |

we obtain

![$\displaystyle U\,\frac{d}{dx}\!\left(\frac{\lambda}{dU/dx}\right) = 2\left[F_2(\lambda)-\lambda\left\{2+F_1(\lambda)\right\}\right] = F(\lambda),$](img3188.png) |

(8.160) |

where

It is generally necessary to integrate Equation (8.158) from the stagnation point at the front of the obstacle, through the

point of maximum tangential velocity, to the separation point on the back side of the obstacle. At the

stagnation point we have  and

and

, which implies that

, which implies that

. Furthermore, at the point of maximum tangential velocity we have

. Furthermore, at the point of maximum tangential velocity we have

and

and  , which implies that

, which implies that

. Finally, as we have already seen,

. Finally, as we have already seen,

at the separation point, which implies, from Equation (8.161), that

at the separation point, which implies, from Equation (8.161), that

.

.

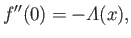

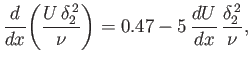

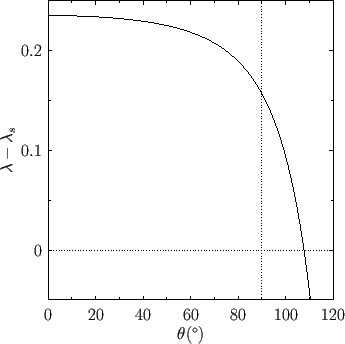

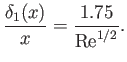

Figure:

The function

(solid curve) and the linear function

(solid curve) and the linear function

(dashed line).

(dashed line).

|

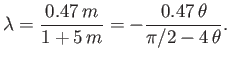

As was first pointed out by Walz (Schlichting 1987), and is illustrated in Figure 8.14, it is a fairly good approximation to

replace

by the linear function

by the linear function

for

for  in the physically relevant range. The approximation is

particularly accurate on the front side of the obstacle (where

in the physically relevant range. The approximation is

particularly accurate on the front side of the obstacle (where  ). Making use of this

approximation, Equations (8.159) and (8.160) reduce to

the linear differential equation

). Making use of this

approximation, Equations (8.159) and (8.160) reduce to

the linear differential equation

|

(8.165) |

which can be integrated to give

|

(8.166) |

assuming that the stagnation point corresponds to  . It follows that

. It follows that

|

(8.167) |

Recall that the separation point corresponds to  , where

, where

.

.

Suppose that  , which corresponds to uniform flow over a flat plate. (See Section 8.5.)

It follows from Equations (8.166) and (8.167) that

, which corresponds to uniform flow over a flat plate. (See Section 8.5.)

It follows from Equations (8.166) and (8.167) that

|

(8.168) |

where

, and

, and  . Moreover, according to Equations (8.148) and (8.162),

. Moreover, according to Equations (8.148) and (8.162),

and

and

. Hence, the displacement width of the boundary layer becomes

. Hence, the displacement width of the boundary layer becomes

|

(8.169) |

This approximate result compares very favorably with the exact result, (8.73).

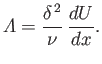

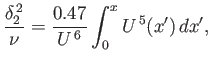

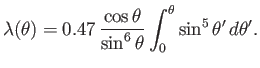

Figure:

The function

for flow around a circular cylinder.

for flow around a circular cylinder.

|

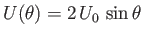

Suppose that

and

and

, which corresponds to uniform transverse flow around a circular cylinder of radius

, which corresponds to uniform transverse flow around a circular cylinder of radius  . (See Section 8.8.) Equation (8.167) yields

. (See Section 8.8.) Equation (8.167) yields

|

(8.170) |

Figure 8.15 shows

determined from the previous formula. It can be seen that

determined from the previous formula. It can be seen that

when

when

. In other words, the separation point is located

. In other words, the separation point is located  from the stagnation point at

the front of the cylinder. This suggests that the low pressure wake behind the cylinder is almost as wide as the

cylinder itself, and that the associated form drag is comparatively large.

from the stagnation point at

the front of the cylinder. This suggests that the low pressure wake behind the cylinder is almost as wide as the

cylinder itself, and that the associated form drag is comparatively large.

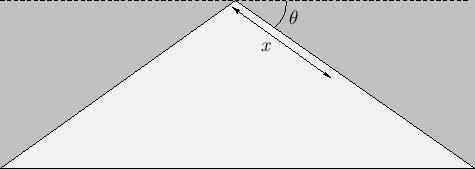

Figure 8.16:

Flow over the back surface of a semi-infinite wedge.

|

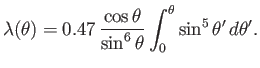

Suppose, finally, that

. If

. If  is negative then, as illustrated in Figure 8.16, this corresponds to uniform flow over the back surface of a semi-infinite

wedge whose angle of dip is

is negative then, as illustrated in Figure 8.16, this corresponds to uniform flow over the back surface of a semi-infinite

wedge whose angle of dip is

|

(8.171) |

(See Section 8.4.)

It follows from Equation (8.167) that

|

(8.172) |

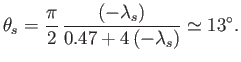

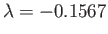

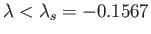

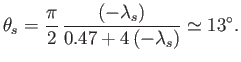

We expect boundary layer separation on the back surface of the wedge when

. This corresponds to

. This corresponds to

, where

, where

|

(8.173) |

Hence, boundary layer separation can be prevented by making the wedge's angle of

dip sufficiently shallow: that is, by streamlining the wedge, which has the effect of reducing the deceleration of the

flow on the wedge's back surface.

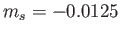

The critical value of  (i.e.,

(i.e.,

) at which separation occurs in our approximate solution is

very similar to the critical value of

) at which separation occurs in our approximate solution is

very similar to the critical value of  (i.e.,

(i.e.,

) at which the exact self-similar solutions described in Section 8.4

can no longer be found. This suggests that the absence of self-similar solutions for

) at which the exact self-similar solutions described in Section 8.4

can no longer be found. This suggests that the absence of self-similar solutions for  is related to

boundary layer separation.

is related to

boundary layer separation.

Next: Exercises

Up: Incompressible Boundary Layers

Previous: Criterion for Boundary Layer

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-03-31

![]() by the linear function

by the linear function

![]() for

for ![]() in the physically relevant range. The approximation is

particularly accurate on the front side of the obstacle (where

in the physically relevant range. The approximation is

particularly accurate on the front side of the obstacle (where ![]() ). Making use of this

approximation, Equations (8.159) and (8.160) reduce to

the linear differential equation

). Making use of this

approximation, Equations (8.159) and (8.160) reduce to

the linear differential equation

![]() , which corresponds to uniform flow over a flat plate. (See Section 8.5.)

It follows from Equations (8.166) and (8.167) that

, which corresponds to uniform flow over a flat plate. (See Section 8.5.)

It follows from Equations (8.166) and (8.167) that

![]() and

and

![]() , which corresponds to uniform transverse flow around a circular cylinder of radius

, which corresponds to uniform transverse flow around a circular cylinder of radius ![]() . (See Section 8.8.) Equation (8.167) yields

. (See Section 8.8.) Equation (8.167) yields

![]() . If

. If ![]() is negative then, as illustrated in Figure 8.16, this corresponds to uniform flow over the back surface of a semi-infinite

wedge whose angle of dip is

is negative then, as illustrated in Figure 8.16, this corresponds to uniform flow over the back surface of a semi-infinite

wedge whose angle of dip is