Next: Approximate Solutions of Boundary

Up: Incompressible Boundary Layers

Previous: Boundary Layer Separation

Criterion for Boundary Layer Separation

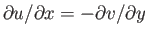

As we have seen, the boundary layer equations (8.110)-(8.113) generally lead to the conclusion that the tangential velocity in a thin boundary layer,  ,

is large compared with the normal velocity,

,

is large compared with the normal velocity,  . Mathematically speaking, this result holds everywhere except in the

immediate vicinity of singular points. But, if

. Mathematically speaking, this result holds everywhere except in the

immediate vicinity of singular points. But, if  then it follows that the fluid moves predominately parallel to the surface

of the obstacle, and can only move away from this surface to a very limited extent. This restriction effectively precludes separation of the flow from the surface. Hence, we conclude

that separation can only occur at a point at which the solution of the boundary layer

equations is singular.

then it follows that the fluid moves predominately parallel to the surface

of the obstacle, and can only move away from this surface to a very limited extent. This restriction effectively precludes separation of the flow from the surface. Hence, we conclude

that separation can only occur at a point at which the solution of the boundary layer

equations is singular.

As we approach a separation point, we expect the flow to deviate from the boundary layer

towards the interior of the fluid. In other words, we expect the normal velocity to become comparable with the

tangential velocity. However, we have seen that the ratio  is of order

is of order

. [See Equation (8.18).] Hence, an increase of

. [See Equation (8.18).] Hence, an increase of  to

such a degree that

to

such a degree that  implies an increase by a factor

implies an increase by a factor

. For sufficiently large Reynolds

numbers, we may suppose that

. For sufficiently large Reynolds

numbers, we may suppose that  effectively increases by an infinite factor. Indeed, if we employ the dimensionless form of the

boundary layer equations, (8.23)-(8.27), the situation just described is formally

equivalent to an infinite value of the dimensionless normal velocity,

effectively increases by an infinite factor. Indeed, if we employ the dimensionless form of the

boundary layer equations, (8.23)-(8.27), the situation just described is formally

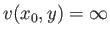

equivalent to an infinite value of the dimensionless normal velocity,  , at the separation point.

, at the separation point.

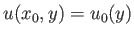

Let the separation point lie at  , and let

, and let  correspond to the region of the boundary layer upstream

of this point. According to the previous discussion,

correspond to the region of the boundary layer upstream

of this point. According to the previous discussion,

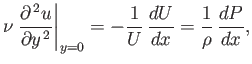

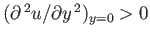

|

(8.121) |

at all  (except, of course,

(except, of course,  , where the boundary conditions at the surface of the obstacle require that

, where the boundary conditions at the surface of the obstacle require that  ).

It follows that the deriviative

).

It follows that the deriviative

is also infinite at

is also infinite at  . Hence, the

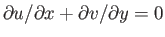

equation of continuity,

. Hence, the

equation of continuity,

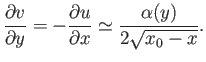

, implies that

, implies that

,

or

,

or

, if

, if  is regarded as a function of

is regarded as a function of  and

and  . Let

. Let

.

Close to the point of separation,

.

Close to the point of separation,  and

and  are small. Thus, we can expand

are small. Thus, we can expand  in powers

of

in powers

of  (at fixed

(at fixed  ). Because

). Because

, the first term in this expansion

vanishes identically, and we are left with

, the first term in this expansion

vanishes identically, and we are left with

![$\displaystyle x_0-x = f(y)\,(u-u_0)^2 + {\cal O}\left[(u-u_0)^3\right],$](img3115.png) |

(8.122) |

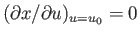

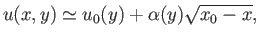

or

|

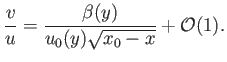

(8.123) |

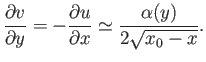

where

is some function of

is some function of  . From the equation of continuity,

. From the equation of continuity,

|

(8.124) |

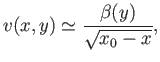

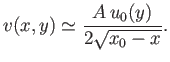

Upon integration, the previous expression yields

|

(8.125) |

where

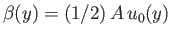

|

(8.126) |

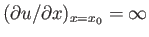

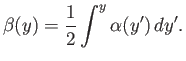

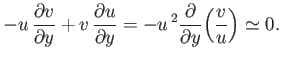

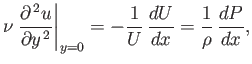

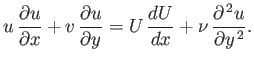

The equation of tangential motion in the boundary layer, (8.111), is written

|

(8.127) |

As is clear from Equation (8.123), the derivative

does not become

infinite as

does not become

infinite as

. The same is true of the function

. The same is true of the function  , which is determined from the

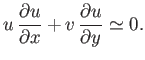

flow outside the boundary layer. However, both terms on the left-hand side of the previous expression become

infinite as

, which is determined from the

flow outside the boundary layer. However, both terms on the left-hand side of the previous expression become

infinite as

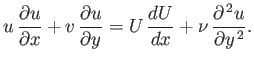

. Hence, in the immediate vicinity of the separation point,

. Hence, in the immediate vicinity of the separation point,

|

(8.128) |

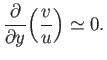

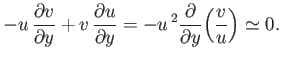

Because

, we can rewrite this equation in the form

, we can rewrite this equation in the form

|

(8.129) |

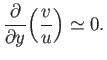

Because  does not, in general, vanish at

does not, in general, vanish at  , we conclude that

, we conclude that

|

(8.130) |

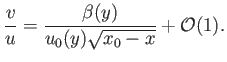

In other words,  is a function of

is a function of  only. From Equations (8.123) and (8.125),

only. From Equations (8.123) and (8.125),

|

(8.131) |

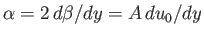

Hence, if this ratio is a function of  alone then

alone then

, where

, where  is a constant: that is,

is a constant: that is,

|

(8.132) |

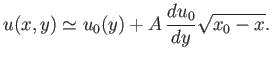

Finally, because Equation (8.126) yields

, we obtain

, we obtain

|

(8.133) |

The previous two expressions specify  and

and  as functions of

as functions of  and

and  near the point of separation. Beyond the point of separation, that is

for

near the point of separation. Beyond the point of separation, that is

for  , the expressions are physically meaningless, because the

square roots become imaginary. This implies that the solutions of the

boundary layer equations cannot sensibly be continued beyond the separation

point.

, the expressions are physically meaningless, because the

square roots become imaginary. This implies that the solutions of the

boundary layer equations cannot sensibly be continued beyond the separation

point.

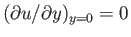

The standard boundary conditions at the surface of the obstacle require

that  at

at  . It, therefore, follows from Equations (8.132) and (8.133) that

. It, therefore, follows from Equations (8.132) and (8.133) that

Thus, we obtain the important prediction that both the

tangential velocity,  , and its first derivative,

, and its first derivative,

, are zero at the separation point (i.e.,

, are zero at the separation point (i.e.,  and

and  ). This result was originally

obtained by Prandtl, although the argument we have used to derive it is due to L.D. Landau (1908-1968) (Landau and Lifshitz 1987).

). This result was originally

obtained by Prandtl, although the argument we have used to derive it is due to L.D. Landau (1908-1968) (Landau and Lifshitz 1987).

If the constant  in expressions (8.132) and (8.133) happens to be

zero then the point

in expressions (8.132) and (8.133) happens to be

zero then the point  and

and  , at which the derivative

, at which the derivative

vanishes,

has no particular properties, and is not a point of separation. However, there is no reason, in

general, why

vanishes,

has no particular properties, and is not a point of separation. However, there is no reason, in

general, why  should take the special value zero. Thus, in practice, a point on the surface

of an obstacle at which

should take the special value zero. Thus, in practice, a point on the surface

of an obstacle at which

is always a point of separation.

is always a point of separation.

Incidentally, if there were no separation at the point  (i.e., if

(i.e., if  ) then we

would have

) then we

would have

for

for  . In other words,

. In other words,  would become negative as we move

away from the surface,

would become negative as we move

away from the surface,  being still small. That is, the fluid beyond the point

being still small. That is, the fluid beyond the point  would move tangentially, in the region of the boundary layer immediately adjacent to the surface, in the

direction opposite to that of the external flow: that is, there would be ``back-flow'' in this region.

In practice, the flow separates from the surface at

would move tangentially, in the region of the boundary layer immediately adjacent to the surface, in the

direction opposite to that of the external flow: that is, there would be ``back-flow'' in this region.

In practice, the flow separates from the surface at  , and the back-flow migrates into the wake.

, and the back-flow migrates into the wake.

The dimensionless boundary layer equations, (8.23)-(8.27), are independent of the Reynolds

number of the external flow (assuming that this number is much greater than unity). Thus, it follows

that the point on the surface of the obstacle at which

is also independent of the

Reynolds number. In other words, the location of the separation point is independent of the Reynolds

number (as long as this number is large, and the flow in the boundary layer is non-turbulent).

is also independent of the

Reynolds number. In other words, the location of the separation point is independent of the Reynolds

number (as long as this number is large, and the flow in the boundary layer is non-turbulent).

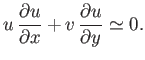

At  , the equation of tangential motion in the boundary layer, (8.111),

is written

, the equation of tangential motion in the boundary layer, (8.111),

is written

|

(8.136) |

where  is the pressure just outside the layer, and use has been made of Equation (8.6). Because

is the pressure just outside the layer, and use has been made of Equation (8.6). Because  is positive, and increases away from the surface (upstream of the separation point), it follows that

is positive, and increases away from the surface (upstream of the separation point), it follows that

at the separation point itself, where

at the separation point itself, where

. Hence, according to the previous equation,

. Hence, according to the previous equation,

In other words, we predict that the external tangential flow is always decelerating at the separation point, whereas the pressure gradient is always

adverse (i.e., such as to decelerate the tangential flow), in agreement with experimental observations.

Next: Approximate Solutions of Boundary

Up: Incompressible Boundary Layers

Previous: Boundary Layer Separation

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-03-31

![]() is of order

is of order

![]() . [See Equation (8.18).] Hence, an increase of

. [See Equation (8.18).] Hence, an increase of ![]() to

such a degree that

to

such a degree that ![]() implies an increase by a factor

implies an increase by a factor

![]() . For sufficiently large Reynolds

numbers, we may suppose that

. For sufficiently large Reynolds

numbers, we may suppose that ![]() effectively increases by an infinite factor. Indeed, if we employ the dimensionless form of the

boundary layer equations, (8.23)-(8.27), the situation just described is formally

equivalent to an infinite value of the dimensionless normal velocity,

effectively increases by an infinite factor. Indeed, if we employ the dimensionless form of the

boundary layer equations, (8.23)-(8.27), the situation just described is formally

equivalent to an infinite value of the dimensionless normal velocity, ![]() , at the separation point.

, at the separation point.

![]() , and let

, and let ![]() correspond to the region of the boundary layer upstream

of this point. According to the previous discussion,

correspond to the region of the boundary layer upstream

of this point. According to the previous discussion,

![]() at

at ![]() . It, therefore, follows from Equations (8.132) and (8.133) that

. It, therefore, follows from Equations (8.132) and (8.133) that

![]() in expressions (8.132) and (8.133) happens to be

zero then the point

in expressions (8.132) and (8.133) happens to be

zero then the point ![]() and

and ![]() , at which the derivative

, at which the derivative

![]() vanishes,

has no particular properties, and is not a point of separation. However, there is no reason, in

general, why

vanishes,

has no particular properties, and is not a point of separation. However, there is no reason, in

general, why ![]() should take the special value zero. Thus, in practice, a point on the surface

of an obstacle at which

should take the special value zero. Thus, in practice, a point on the surface

of an obstacle at which

![]() is always a point of separation.

is always a point of separation.

![]() (i.e., if

(i.e., if ![]() ) then we

would have

) then we

would have

![]() for

for ![]() . In other words,

. In other words, ![]() would become negative as we move

away from the surface,

would become negative as we move

away from the surface, ![]() being still small. That is, the fluid beyond the point

being still small. That is, the fluid beyond the point ![]() would move tangentially, in the region of the boundary layer immediately adjacent to the surface, in the

direction opposite to that of the external flow: that is, there would be ``back-flow'' in this region.

In practice, the flow separates from the surface at

would move tangentially, in the region of the boundary layer immediately adjacent to the surface, in the

direction opposite to that of the external flow: that is, there would be ``back-flow'' in this region.

In practice, the flow separates from the surface at ![]() , and the back-flow migrates into the wake.

, and the back-flow migrates into the wake.

![]() is also independent of the

Reynolds number. In other words, the location of the separation point is independent of the Reynolds

number (as long as this number is large, and the flow in the boundary layer is non-turbulent).

is also independent of the

Reynolds number. In other words, the location of the separation point is independent of the Reynolds

number (as long as this number is large, and the flow in the boundary layer is non-turbulent).

![]() , the equation of tangential motion in the boundary layer, (8.111),

is written

, the equation of tangential motion in the boundary layer, (8.111),

is written