Next: Van der Waals Gas

Up: Classical Thermodynamics

Previous: General Relation Between Specific

Consider a rigid container that is thermally insulated. The container is divided into two

compartments separated by a valve that is initially closed. One compartment, of volume  ,

contains the gas under investigation. The other compartment is empty. The initial temperature of the

system is

,

contains the gas under investigation. The other compartment is empty. The initial temperature of the

system is  . The valve is now opened, and the gas is free to expand so as to fill the entire

container, whose volume is

. The valve is now opened, and the gas is free to expand so as to fill the entire

container, whose volume is  . What is the temperature,

. What is the temperature,  , of the gas after the final

equilibrium state has been reached?

, of the gas after the final

equilibrium state has been reached?

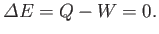

Because the system consisting of the gas and the container is adiabatically insulated, no heat flows

into the system: that is,

|

(6.144) |

Furthermore, the system does no work in the expansion process: that is,

|

(6.145) |

It follows from the first law of thermodynamics that the total energy of the system is

conserved: that is,

|

(6.146) |

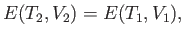

Let us assume that the container itself has negligible heat capacity (which, it turns out, is not a particularly realistic assumption--see later), so that the internal energy of the container does not

change. Under these circumstances, the energy change of the system is equivalent to that of the gas.

The conservation of energy, (6.146), thus reduces to

|

(6.147) |

where  is the gas's internal energy.

is the gas's internal energy.

To predict the outcome of the experiment, it is only necessary to know the internal energy of the gas,

, as a function of the temperature and the volume. If the initial parameters,

, as a function of the temperature and the volume. If the initial parameters,  and

and

, are known, as well as the final volume,

, are known, as well as the final volume,  , then Equation (6.147) yields

an equation that specifies the unknown final temperature,

, then Equation (6.147) yields

an equation that specifies the unknown final temperature,  .

.

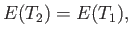

For an ideal gas, the internal energy is independent of the volume: that is,  . (See Section 6.2.)

In this case, Equation (6.147) yields

. (See Section 6.2.)

In this case, Equation (6.147) yields

|

(6.148) |

which implies that  . In other words, there is no temperature change in the free expansion

of an ideal gas.

. In other words, there is no temperature change in the free expansion

of an ideal gas.

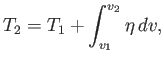

The change in temperature of an non-ideal gas that undergoes free expansion can be written

|

(6.149) |

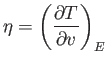

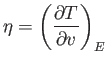

where

|

(6.150) |

is termed the Joule coefficient. Here,  is the molar volume, where

is the molar volume, where  is the number of moles

of gas in the container. Furthermore,

is the number of moles

of gas in the container. Furthermore,

and

and

.

.

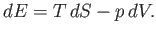

According to the first law of thermodynamics,

|

(6.151) |

However, if the internal energy is constant then we can write

![$\displaystyle 0=T\left[\left(\frac{\partial S}{\partial T}\right)_VdT + \left(\frac{\partial S}{\partial V}\right)_TdV\right]-p dV.$](img1093.png) |

(6.152) |

With the aid of Equations (6.109) and (6.120), this becomes

![$\displaystyle 0=C_V dT + \left[T\left(\frac{\partial p}{\partial T}\right)_V -p\right]dV.$](img1094.png) |

(6.153) |

Hence,

![$\displaystyle \left(\frac{\partial T}{\partial V}\right)_E =-\left.\left[T\left(\frac{\partial p}{\partial T}\right)_V -p\right]\right/C_V,$](img1095.png) |

(6.154) |

and the Joule coefficient can be written

![$\displaystyle \eta = -\left.\left[T\left(\frac{\partial p}{\partial T}\right)_V...

...ight]\right/c_V = -\left.\left(\frac{T \alpha_V}{\kappa_T}-p\right)\right/c_V.$](img1096.png) |

(6.155) |

[See Equation (6.132).]

Note that all terms on the right-hand side of the previous expression are easily measurable.

Next: Van der Waals Gas

Up: Classical Thermodynamics

Previous: General Relation Between Specific

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-25

![]() , as a function of the temperature and the volume. If the initial parameters,

, as a function of the temperature and the volume. If the initial parameters, ![]() and

and

![]() , are known, as well as the final volume,

, are known, as well as the final volume, ![]() , then Equation (6.147) yields

an equation that specifies the unknown final temperature,

, then Equation (6.147) yields

an equation that specifies the unknown final temperature, ![]() .

.

![]() . (See Section 6.2.)

In this case, Equation (6.147) yields

. (See Section 6.2.)

In this case, Equation (6.147) yields

![$\displaystyle 0=T\left[\left(\frac{\partial S}{\partial T}\right)_VdT + \left(\frac{\partial S}{\partial V}\right)_TdV\right]-p dV.$](img1093.png)

![$\displaystyle 0=C_V dT + \left[T\left(\frac{\partial p}{\partial T}\right)_V -p\right]dV.$](img1094.png)

![$\displaystyle \left(\frac{\partial T}{\partial V}\right)_E =-\left.\left[T\left(\frac{\partial p}{\partial T}\right)_V -p\right]\right/C_V,$](img1095.png)