Next: Sommerfeld Expansion

Up: Quantum Statistics

Previous: Stefan-Boltzmann Law

Conduction Electrons in Metal

The conduction electrons in a metal are non-localized (i.e., they are

not tied to any particular atoms). In conventional metals, each atom contributes

a fixed number of such electrons (corresponding to its valency). To a first approximation, it is possible

to neglect the mutual interaction of the conduction electrons, because this

interaction

is largely shielded out by the stationary ions. The conduction electrons

can, therefore, be treated as an ideal gas. However, the concentration of

such electrons in a metal far exceeds the concentration of

particles in a conventional gas. It is, therefore, not surprising that

conduction electrons cannot normally be analyzed using classical statistics:

in fact, they are subject to Fermi-Dirac statistics

(because electrons are fermions).

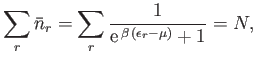

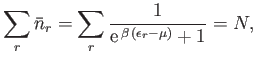

Recall, from Section 8.5, that the mean number of particles occupying

state  (energy

(energy

) is given by

) is given by

|

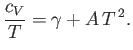

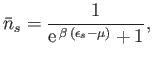

(8.134) |

according to the Fermi-Dirac distribution. Here,

|

(8.135) |

is termed the Fermi energy of the system. This energy is

determined by the condition that

|

(8.136) |

where  is the total number of particles contained in the volume

is the total number of particles contained in the volume  .

It is clear, from the previous equation, that the Fermi energy,

.

It is clear, from the previous equation, that the Fermi energy,  , is generally

a function of the temperature,

, is generally

a function of the temperature,  .

.

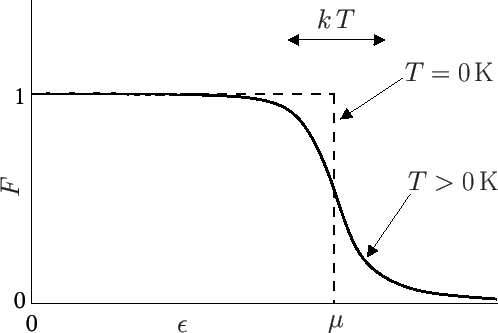

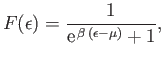

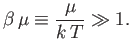

Let us investigate the behavior of the so-called Fermi function,

|

(8.137) |

as  varies. Here, the energy is measured from

its lowest possible value

varies. Here, the energy is measured from

its lowest possible value

. If the Fermi energy,

. If the Fermi energy,  , is

such that

, is

such that

then

then

,

and

,

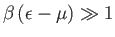

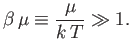

and  reduces to the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. However,

for the case of conduction electrons in a metal, we are interested in

the opposite limit, where

reduces to the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. However,

for the case of conduction electrons in a metal, we are interested in

the opposite limit, where

|

(8.138) |

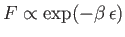

In this limit, if

then

then

,

so that

,

so that

. On the other hand, if

. On the other hand, if

then

then

, so that

, so that

![$ F(\epsilon)=

\exp[-\beta (\epsilon-\mu)]$](img2238.png) falls off exponentially with increasing

falls off exponentially with increasing

, just like a classical Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. Note that

, just like a classical Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. Note that

when

when

. The transition region in which

. The transition region in which  goes from

a value close to unity to a value close to zero corresponds to an

energy interval of order

goes from

a value close to unity to a value close to zero corresponds to an

energy interval of order  , centered on

, centered on

. In fact,

. In fact,  when

when

, and

, and  when

when

. The behavior of the Fermi function is

illustrated in Figure 8.4.

. The behavior of the Fermi function is

illustrated in Figure 8.4.

Figure 8.4:

The Fermi function.

|

In the limit as

, the transition region becomes

infinitesimally narrow. In this case,

, the transition region becomes

infinitesimally narrow. In this case,  for

for

, and

, and

for

for

, as illustrated in Figure 8.4.

This is an obvious result, because when

, as illustrated in Figure 8.4.

This is an obvious result, because when  the conduction

electrons attain their lowest energy, or ground-state, configuration.

Because the Pauli exclusion principle requires that there be no

more than one electron per single-particle quantum state, the lowest

energy configuration is obtained by piling

electrons into the lowest available unoccupied states, until all of

the electrons are used up. Thus, the last electron added to the

pile has a quite considerable energy,

the conduction

electrons attain their lowest energy, or ground-state, configuration.

Because the Pauli exclusion principle requires that there be no

more than one electron per single-particle quantum state, the lowest

energy configuration is obtained by piling

electrons into the lowest available unoccupied states, until all of

the electrons are used up. Thus, the last electron added to the

pile has a quite considerable energy,

, because all of the

lower energy states are already occupied. Clearly, the exclusion principle

implies that a Fermi-Dirac gas possesses a large mean energy, even at absolute

zero.

, because all of the

lower energy states are already occupied. Clearly, the exclusion principle

implies that a Fermi-Dirac gas possesses a large mean energy, even at absolute

zero.

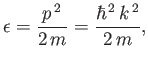

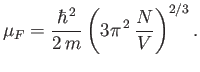

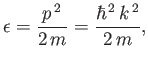

Let us calculate the Fermi energy,  , of a Fermi-Dirac

gas at

, of a Fermi-Dirac

gas at  . The energy of each particle is related to its

momentum

. The energy of each particle is related to its

momentum

via

via

|

(8.139) |

where  is the de Broglie wavevector. Here,

is the de Broglie wavevector. Here,  is the electron mass.

At

is the electron mass.

At  , all quantum states

whose energy is less than the Fermi energy,

, all quantum states

whose energy is less than the Fermi energy,  , are filled. The

Fermi energy corresponds to a so-called Fermi momentum,

, are filled. The

Fermi energy corresponds to a so-called Fermi momentum,

, which

is such that

, which

is such that

|

(8.140) |

Thus, at  , all quantum states with

, all quantum states with  are filled, and all

those with

are filled, and all

those with  are empty.

are empty.

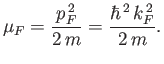

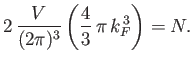

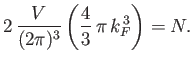

Now, we know, by analogy with Equation (7.183), that there are

allowable translational states per unit volume of

allowable translational states per unit volume of  -space. The volume of

the sphere of radius

-space. The volume of

the sphere of radius  in

in  -space is

-space is

. It

follows that the Fermi sphere of radius

. It

follows that the Fermi sphere of radius  contains

contains

translational states. The number of

quantum states inside the sphere is twice this, because electrons

possess two possible spin states for every possible translational state. Because the

total number of occupied states (i.e., the total number of quantum

states inside the Fermi sphere) must equal the total number of particles

in the gas, it follows that

translational states. The number of

quantum states inside the sphere is twice this, because electrons

possess two possible spin states for every possible translational state. Because the

total number of occupied states (i.e., the total number of quantum

states inside the Fermi sphere) must equal the total number of particles

in the gas, it follows that

|

(8.141) |

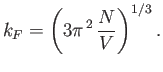

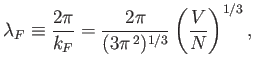

The previous expression can be rearranged to

give

|

(8.142) |

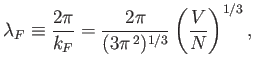

Hence,

|

(8.143) |

which implies that the de Broglie wavelength,  ,

corresponding to the Fermi energy, is of order the mean separation

between particles

,

corresponding to the Fermi energy, is of order the mean separation

between particles

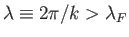

. All quantum states with de Broglie

wavelengths

. All quantum states with de Broglie

wavelengths

are occupied

at

are occupied

at  , whereas all those with

, whereas all those with

are empty.

are empty.

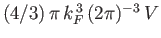

According to Equations (8.140) and (8.142), the Fermi energy at  takes the form

takes the form

|

(8.144) |

It is easily demonstrated that

for conventional metals

at room temperature. (See Exercise 17.)

for conventional metals

at room temperature. (See Exercise 17.)

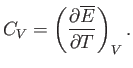

The majority of the conduction electrons in a metal occupy a

band of completely filled states with energies far below the Fermi

energy. In many cases, such electrons have very little effect

on the macroscopic properties of the metal. Consider, for example, the

contribution of the conduction electrons to the specific heat of the metal.

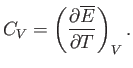

The heat capacity at constant volume,  , of these electrons can

be calculated from a knowledge of their mean energy,

, of these electrons can

be calculated from a knowledge of their mean energy,

, as a

function of

, as a

function of  : that is,

: that is,

|

(8.145) |

If the electrons obeyed classical Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics, so that

for all electrons, then the

equipartition theorem would give

for all electrons, then the

equipartition theorem would give

However, the actual situation, in which  has the form shown in Figure 8.4,

is very different. A small change in

has the form shown in Figure 8.4,

is very different. A small change in  does not affect the

mean energies of

the majority of the electrons, with

does not affect the

mean energies of

the majority of the electrons, with

, because these electrons

lie in states that are completely filled, and remain so when the temperature

is changed. It follows that these electrons contribute nothing whatsoever to

the heat capacity. On the other hand, the relatively small number of

electrons,

, because these electrons

lie in states that are completely filled, and remain so when the temperature

is changed. It follows that these electrons contribute nothing whatsoever to

the heat capacity. On the other hand, the relatively small number of

electrons,

, in the energy range of order

, in the energy range of order  , centered on the

Fermi energy, in which

, centered on the

Fermi energy, in which  is significantly different from 0 and 1,

do contribute to the specific heat. In the tail end of this region,

is significantly different from 0 and 1,

do contribute to the specific heat. In the tail end of this region,

, so the

distribution reverts to a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution.

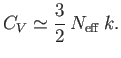

Hence, from Equation (8.147),

we expect each electron in this region to contribute roughly an amount

, so the

distribution reverts to a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution.

Hence, from Equation (8.147),

we expect each electron in this region to contribute roughly an amount

to the heat capacity. Hence, the heat capacity

can be written

to the heat capacity. Hence, the heat capacity

can be written

|

(8.148) |

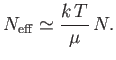

However, because only a fraction  of the total conduction

electrons lie in the tail region of the Fermi-Dirac distribution, we

expect

of the total conduction

electrons lie in the tail region of the Fermi-Dirac distribution, we

expect

|

(8.149) |

It follows that

|

(8.150) |

Because

in conventional metals, the molar specific heat of

the conduction electrons is clearly very much less than the classical value

in conventional metals, the molar specific heat of

the conduction electrons is clearly very much less than the classical value

. This accounts for the fact that

the molar specific heat capacities of metals at room temperature are

about the same as those of insulators. Before the advent of

quantum mechanics, the classical theory predicted incorrectly that the

presence of conduction electrons should raise the heat capacities of monovalent

metals by 50 percent [i.e.,

. This accounts for the fact that

the molar specific heat capacities of metals at room temperature are

about the same as those of insulators. Before the advent of

quantum mechanics, the classical theory predicted incorrectly that the

presence of conduction electrons should raise the heat capacities of monovalent

metals by 50 percent [i.e.,  ] compared to those of insulators.

] compared to those of insulators.

Note that the specific heat (8.150) is not temperature independent.

In fact, using the superscript  to denote the electronic

specific heat, the molar specific heat can be written

to denote the electronic

specific heat, the molar specific heat can be written

|

(8.151) |

where  is a (positive) constant of proportionality.

At room temperature

is a (positive) constant of proportionality.

At room temperature  is completely masked by the much

larger specific heat,

is completely masked by the much

larger specific heat,  , due to lattice vibrations. However, at

very low temperatures

, due to lattice vibrations. However, at

very low temperatures

, where

, where  is a (positive)

constant of proportionality. (See Section 7.14.) Clearly,

at low temperatures,

is a (positive)

constant of proportionality. (See Section 7.14.) Clearly,

at low temperatures,

approaches zero far more rapidly that

the electronic specific heat, as

approaches zero far more rapidly that

the electronic specific heat, as  is reduced. Hence, it should be possible

to measure the electronic contribution to the molar specific

heat at low temperatures.

is reduced. Hence, it should be possible

to measure the electronic contribution to the molar specific

heat at low temperatures.

The total molar specific heat of a metal at low temperatures takes the

form

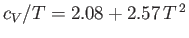

|

(8.152) |

Hence,

|

(8.153) |

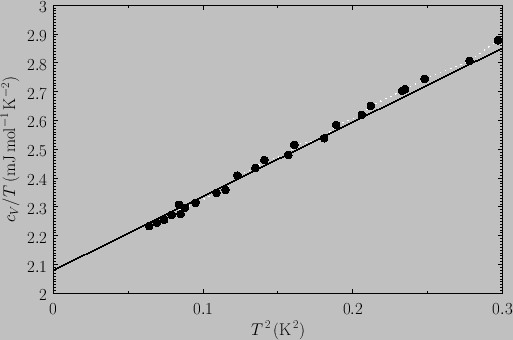

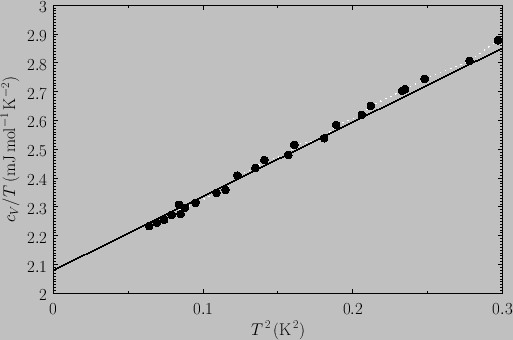

It follows that a plot of  versus

versus  should yield a

straight-line whose intercept on the vertical axis gives the

coefficient

should yield a

straight-line whose intercept on the vertical axis gives the

coefficient  . Figure 8.5 shows such a plot.

The fact that a good straight-line is obtained verifies that the temperature

dependence of the heat capacity predicted by Equation (8.152) is indeed

correct.

. Figure 8.5 shows such a plot.

The fact that a good straight-line is obtained verifies that the temperature

dependence of the heat capacity predicted by Equation (8.152) is indeed

correct.

Figure:

The low-temperature heat capacity of potassium, plotted as  versus

versus

. The straight-line shows the fit

. The straight-line shows the fit

. From C. Kittel, and H. Kroemer, Thermal Physics (W.H. Freeman & co., New York NY, 1980).

. From C. Kittel, and H. Kroemer, Thermal Physics (W.H. Freeman & co., New York NY, 1980).

|

Next: Sommerfeld Expansion

Up: Quantum Statistics

Previous: Stefan-Boltzmann Law

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-25

![]() (energy

(energy

![]() ) is given by

) is given by

![]() , the transition region becomes

infinitesimally narrow. In this case,

, the transition region becomes

infinitesimally narrow. In this case, ![]() for

for

![]() , and

, and

![]() for

for

![]() , as illustrated in Figure 8.4.

This is an obvious result, because when

, as illustrated in Figure 8.4.

This is an obvious result, because when ![]() the conduction

electrons attain their lowest energy, or ground-state, configuration.

Because the Pauli exclusion principle requires that there be no

more than one electron per single-particle quantum state, the lowest

energy configuration is obtained by piling

electrons into the lowest available unoccupied states, until all of

the electrons are used up. Thus, the last electron added to the

pile has a quite considerable energy,

the conduction

electrons attain their lowest energy, or ground-state, configuration.

Because the Pauli exclusion principle requires that there be no

more than one electron per single-particle quantum state, the lowest

energy configuration is obtained by piling

electrons into the lowest available unoccupied states, until all of

the electrons are used up. Thus, the last electron added to the

pile has a quite considerable energy,

![]() , because all of the

lower energy states are already occupied. Clearly, the exclusion principle

implies that a Fermi-Dirac gas possesses a large mean energy, even at absolute

zero.

, because all of the

lower energy states are already occupied. Clearly, the exclusion principle

implies that a Fermi-Dirac gas possesses a large mean energy, even at absolute

zero.

![]() , of a Fermi-Dirac

gas at

, of a Fermi-Dirac

gas at ![]() . The energy of each particle is related to its

momentum

. The energy of each particle is related to its

momentum

![]() via

via

![]() allowable translational states per unit volume of

allowable translational states per unit volume of ![]() -space. The volume of

the sphere of radius

-space. The volume of

the sphere of radius ![]() in

in ![]() -space is

-space is

![]() . It

follows that the Fermi sphere of radius

. It

follows that the Fermi sphere of radius ![]() contains

contains

![]() translational states. The number of

quantum states inside the sphere is twice this, because electrons

possess two possible spin states for every possible translational state. Because the

total number of occupied states (i.e., the total number of quantum

states inside the Fermi sphere) must equal the total number of particles

in the gas, it follows that

translational states. The number of

quantum states inside the sphere is twice this, because electrons

possess two possible spin states for every possible translational state. Because the

total number of occupied states (i.e., the total number of quantum

states inside the Fermi sphere) must equal the total number of particles

in the gas, it follows that

![]() takes the form

takes the form

![]() , of these electrons can

be calculated from a knowledge of their mean energy,

, of these electrons can

be calculated from a knowledge of their mean energy,

![]() , as a

function of

, as a

function of ![]() : that is,

: that is,

![]() in conventional metals, the molar specific heat of

the conduction electrons is clearly very much less than the classical value

in conventional metals, the molar specific heat of

the conduction electrons is clearly very much less than the classical value

![]() . This accounts for the fact that

the molar specific heat capacities of metals at room temperature are

about the same as those of insulators. Before the advent of

quantum mechanics, the classical theory predicted incorrectly that the

presence of conduction electrons should raise the heat capacities of monovalent

metals by 50 percent [i.e.,

. This accounts for the fact that

the molar specific heat capacities of metals at room temperature are

about the same as those of insulators. Before the advent of

quantum mechanics, the classical theory predicted incorrectly that the

presence of conduction electrons should raise the heat capacities of monovalent

metals by 50 percent [i.e., ![]() ] compared to those of insulators.

] compared to those of insulators.

![]() to denote the electronic

specific heat, the molar specific heat can be written

to denote the electronic

specific heat, the molar specific heat can be written