Next: Stefan-Boltzmann Law

Up: Quantum Statistics

Previous: Planck Radiation Law

Suppose that we were to make a small hole in the wall of our enclosure,

and observe the emitted radiation. A small hole is the best approximation in

physics to a black-body, which is defined as an object that absorbs, and,

therefore, emits, radiation perfectly at all wavelengths.

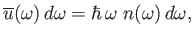

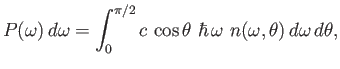

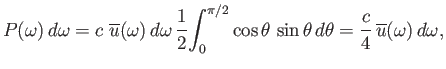

What is the power radiated by the hole? Well, the power density inside the enclosure

can be written

|

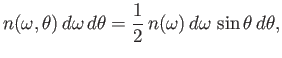

(8.119) |

where  is the mean

number of photons per unit volume whose frequencies lie

in the range

is the mean

number of photons per unit volume whose frequencies lie

in the range  to

to

. The radiation field inside the

enclosure is isotropic (we are assuming that the hole is sufficiently small that

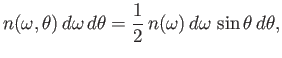

it does not distort the field). It follows that the mean number of photons

per unit volume

whose frequencies lie in the specified range, and

whose directions of propagation make an angle in the range

. The radiation field inside the

enclosure is isotropic (we are assuming that the hole is sufficiently small that

it does not distort the field). It follows that the mean number of photons

per unit volume

whose frequencies lie in the specified range, and

whose directions of propagation make an angle in the range

to

to

with the normal to the hole, is

with the normal to the hole, is

|

(8.120) |

where

is proportional to the solid angle in the specified

range of directions,

and

is proportional to the solid angle in the specified

range of directions,

and

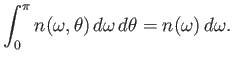

|

(8.121) |

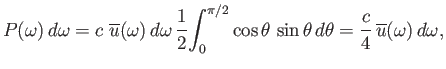

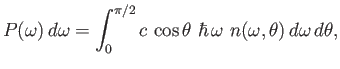

Photons travel at the velocity of light, so the power per unit area escaping from

the hole in the frequency range  to

to

is

is

|

(8.122) |

where

is the component of the photon velocity in the direction

of the hole.

This gives

is the component of the photon velocity in the direction

of the hole.

This gives

|

(8.123) |

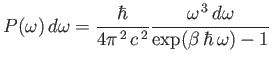

so

|

(8.124) |

is the power per unit area radiated by a black-body in the frequency range

to

to

.

.

A black-body is very much an idealization. The power

spectra of real radiating bodies

can deviate quite substantially from black-body spectra. Nevertheless, we

can make some useful predictions using this model. The black-body power spectrum

peaks when

. (See Exercise 15.) This means that the peak radiation

frequency scales linearly with the temperature of the body. In other words,

hot bodies tend to radiate at higher frequencies than cold bodies. This

result (in particular, the linear scaling) is known as Wien's displacement

law. It allows us to estimate the surface temperatures of stars from their

colors (surprisingly enough, stars are fairly good black-bodies). Table 8.4 shows

some stellar temperatures determined by this method (in fact,

the whole emission spectrum is fitted to a black-body spectrum).

It can be seen that the

apparent colors (which correspond quite well to the colors of the peak radiation)

scan the whole visible spectrum, from red to blue, as the stellar surface temperatures

gradually rise.

. (See Exercise 15.) This means that the peak radiation

frequency scales linearly with the temperature of the body. In other words,

hot bodies tend to radiate at higher frequencies than cold bodies. This

result (in particular, the linear scaling) is known as Wien's displacement

law. It allows us to estimate the surface temperatures of stars from their

colors (surprisingly enough, stars are fairly good black-bodies). Table 8.4 shows

some stellar temperatures determined by this method (in fact,

the whole emission spectrum is fitted to a black-body spectrum).

It can be seen that the

apparent colors (which correspond quite well to the colors of the peak radiation)

scan the whole visible spectrum, from red to blue, as the stellar surface temperatures

gradually rise.

Table 8.4:

Physical properties of some well-known stars.

| Name |

Constellation |

Spectral Type |

Surface Temp. (K) |

Color |

| Antares |

Scorpio |

M |

3300 |

Very Red |

| Aldebaran |

Taurus |

K |

3800 |

Reddish Yellow |

| Sun |

|

G |

5770 |

Yellow |

| Procyon |

Canis Minor |

F |

6570 |

Yellowish White |

| Sirius |

Canis Major |

A |

9250 |

White |

| Rigel |

Orion |

B |

11,200 |

Bluish White |

|

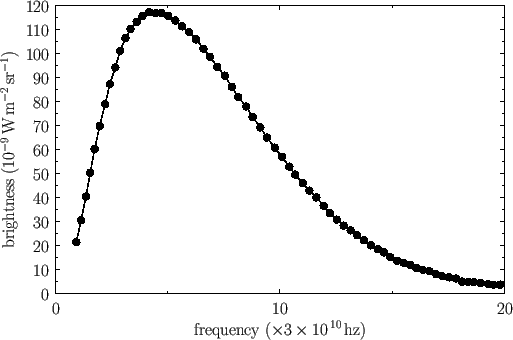

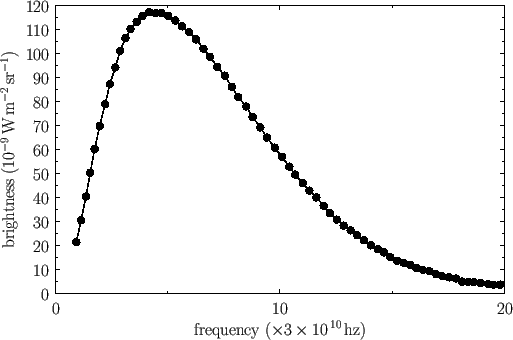

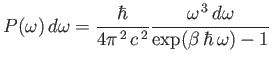

Probably the most famous black-body spectrum is cosmological in origin. Just after

the ``big bang,'' the universe was essentially a ``fireball,'' with the energy associated with

radiation completely dominating that associated with

matter. The early universe was also fairly

well described by equilibrium statistical thermodynamics,

which means that the radiation had a black-body spectrum. As the universe expanded,

the radiation was gradually Doppler shifted to ever larger wavelengths (in other

words, the radiation did work against the expansion of the universe, and, thereby,

lost energy--see Exercise 13), but its spectrum remained invariant. Nowadays, this primordial

radiation is detectable as a faint microwave background that pervades the

whole universe. The microwave background was discovered accidentally by Penzias

and Wilson in 1961. Until recently, it was difficult to measure the full

spectrum with any degree of

precision, because of strong microwave absorption and scattering by

the Earth's atmosphere. However, all of this changed when the COBE satellite

was launched in 1989. It took precisely nine minutes to measure the perfect

black-body spectrum reproduced in Figure 8.3.

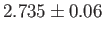

This data can be fitted to a black-body

curve of characteristic

temperature  K. In a very real sense, this can be regarded

as the ``temperature of the universe.''

K. In a very real sense, this can be regarded

as the ``temperature of the universe.''

Figure:

Cosmic background radiation spectrum measured by the

Far Infrared Absolute Spectrometer (FIRAS) aboard the Cosmic Background

Explorer satellite (COBE). The fit is to a black-body spectrum of characteristic temperature

K.

[Data from J.C. Mather, et al., Astrophysical Journal Letters 354, L37 (1990).]

K.

[Data from J.C. Mather, et al., Astrophysical Journal Letters 354, L37 (1990).]

|

Next: Stefan-Boltzmann Law

Up: Quantum Statistics

Previous: Planck Radiation Law

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-25

![]() . (See Exercise 15.) This means that the peak radiation

frequency scales linearly with the temperature of the body. In other words,

hot bodies tend to radiate at higher frequencies than cold bodies. This

result (in particular, the linear scaling) is known as Wien's displacement

law. It allows us to estimate the surface temperatures of stars from their

colors (surprisingly enough, stars are fairly good black-bodies). Table 8.4 shows

some stellar temperatures determined by this method (in fact,

the whole emission spectrum is fitted to a black-body spectrum).

It can be seen that the

apparent colors (which correspond quite well to the colors of the peak radiation)

scan the whole visible spectrum, from red to blue, as the stellar surface temperatures

gradually rise.

. (See Exercise 15.) This means that the peak radiation

frequency scales linearly with the temperature of the body. In other words,

hot bodies tend to radiate at higher frequencies than cold bodies. This

result (in particular, the linear scaling) is known as Wien's displacement

law. It allows us to estimate the surface temperatures of stars from their

colors (surprisingly enough, stars are fairly good black-bodies). Table 8.4 shows

some stellar temperatures determined by this method (in fact,

the whole emission spectrum is fitted to a black-body spectrum).

It can be seen that the

apparent colors (which correspond quite well to the colors of the peak radiation)

scan the whole visible spectrum, from red to blue, as the stellar surface temperatures

gradually rise.

![]() K. In a very real sense, this can be regarded

as the ``temperature of the universe.''

K. In a very real sense, this can be regarded

as the ``temperature of the universe.''