Next: Schrödinger Wave Equation

Up: Quantum Dynamics

Previous: Heisenberg Equation of Motion

We have now introduced all of the basic elements of quantum mechanics. The only

element that is lacking is some rule to determine the form of the

quantum mechanical Hamiltonian. For a physical system that possess a classical

analog, we generally assume that the Hamiltonian has the same form as

in classical physics (i.e., we replace the classical coordinates and conjugate

momenta by the corresponding quantum mechanical operators). This scheme guarantees

that quantum mechanics yields the correct classical equations of motion

in the classical limit. Whenever an ambiguity arises because of

non-commuting

observables, this can usually be resolved by requiring the Hamiltonian  to

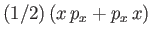

be an Hermitian operator. For instance, we would write the

quantum mechanical analog of the classical product

to

be an Hermitian operator. For instance, we would write the

quantum mechanical analog of the classical product  , appearing in the

Hamiltonian, as the Hermitian product

, appearing in the

Hamiltonian, as the Hermitian product

. When the system

in question has no classical analog then we are reduced to guessing a form

for

. When the system

in question has no classical analog then we are reduced to guessing a form

for  that reproduces the observed behavior of the system.

that reproduces the observed behavior of the system.

Consider a three-dimensional system characterized by three independent Cartesian

position coordinates  (where

(where  runs from 1 to 3), with three corresponding

conjugate momenta

runs from 1 to 3), with three corresponding

conjugate momenta  . These are represented by three commuting position

operators

. These are represented by three commuting position

operators  , and three commuting momentum operators

, and three commuting momentum operators  , respectively. The

commutation

relations satisfied by the position and momentum operators

are

, respectively. The

commutation

relations satisfied by the position and momentum operators

are

![$\displaystyle [x_i, p_j] = {\rm i}\,\hbar\, \delta_{ij}.$](img647.png) |

(3.32) |

[See Equation (2.25).]

It is helpful to denote

as

as  and

and

as

as

. The following useful formulae,

. The following useful formulae,

where

and

and

are functions that can be expanded as power series, are

easily proved using the fundamental commutation relations, Equations (3.32). (See Exercise 1.)

are functions that can be expanded as power series, are

easily proved using the fundamental commutation relations, Equations (3.32). (See Exercise 1.)

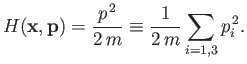

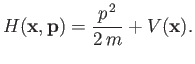

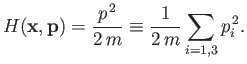

Let us now consider the three-dimensional motion of a free particle of mass

in the

Heisenberg picture. The Hamiltonian is assumed to have the same form as in

classical physics: that is,

in the

Heisenberg picture. The Hamiltonian is assumed to have the same form as in

classical physics: that is,

|

(3.35) |

In the following, all dynamical variables are assumed to be Heisenberg dynamical

variables, although we will omit the subscript  for the sake of clarity.

The time evolution of the momentum operator

for the sake of clarity.

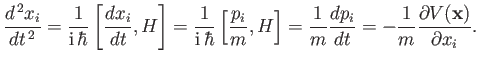

The time evolution of the momentum operator  follows from the Heisenberg

equation of motion, Equation (3.25). We find that

follows from the Heisenberg

equation of motion, Equation (3.25). We find that

![$\displaystyle \frac{dp_i}{dt} = \frac{1}{{\rm i}\,\hbar}\,[p_i, H] = 0,$](img659.png) |

(3.36) |

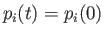

because  automatically commutes with any function of the momentum operators.

Thus, for a free particle, the momentum operators are constants of the motion,

which means that

automatically commutes with any function of the momentum operators.

Thus, for a free particle, the momentum operators are constants of the motion,

which means that

at all times

at all times  (for

(for  is 1 to 3).

The time evolution of the position operator

is 1 to 3).

The time evolution of the position operator  is given by

is given by

![$\displaystyle \frac{d x_i}{dt} = \frac{1}{{\rm i}\,\hbar}\, [x_i, H] = \frac{1}...

... p_i}\! \left(\sum_{j=1,3} p_j^{\,2}\right) = \frac{p_i}{m} = \frac{p_i(0)}{m},$](img661.png) |

(3.37) |

where use has been made of Equation (3.33). It follows that

![$\displaystyle x_i(t) = x_i(0) + \left[\frac{p_i(0)}{m}\right] t,$](img662.png) |

(3.38) |

which is analogous to the equation of motion of a classical free particle.

Note that, even though

![$\displaystyle [x_i(0), x_j(0)] = 0,$](img663.png) |

(3.39) |

where the position operators are evaluated at equal times, the  do not

commute when evaluated at different times. For instance,

do not

commute when evaluated at different times. For instance,

![$\displaystyle [x_i(t), x_i(0)] = \left[ \frac{p_i(0)\,t}{m}, x_i(0)\right] = \frac{-{\rm i}\,\hbar \,t} {m}.$](img664.png) |

(3.40) |

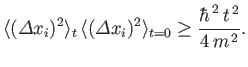

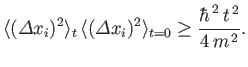

Combining the previous commutation relation with the uncertainty relation (1.86) yields

|

(3.41) |

This result implies that, even if a particle is well localized at  , its

position becomes progressively more uncertain with time. This conclusion

can also be obtained by studying the propagation of wavepackets in

wave mechanics.

, its

position becomes progressively more uncertain with time. This conclusion

can also be obtained by studying the propagation of wavepackets in

wave mechanics.

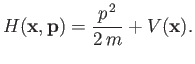

Let us now add a potential

to our free particle Hamiltonian:

to our free particle Hamiltonian:

|

(3.42) |

Here,  is some (real) function of the

is some (real) function of the  operators. The Heisenberg equation of

motion gives

operators. The Heisenberg equation of

motion gives

![$\displaystyle \frac{d p_i}{dt} = \frac{1}{{\rm i}\,\hbar} \,[p_i, V({\bf x})] = - \frac{\partial V({\bf x})}{\partial x_i},$](img670.png) |

(3.43) |

where use has been made of Equation (3.34). On the other hand, the result

|

(3.44) |

still holds, because the  all commute with the new term,

all commute with the new term,

, in the

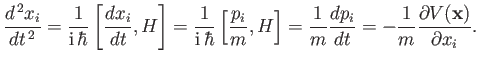

Hamiltonian. We can use the Heisenberg equation of motion a second time

to deduce that

, in the

Hamiltonian. We can use the Heisenberg equation of motion a second time

to deduce that

|

(3.45) |

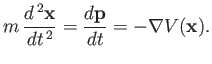

In vectorial form, this equation becomes

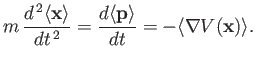

|

(3.46) |

This is the quantum mechanical equivalent of Newton's second law of motion.

Taking the expectation values of both sides with respect to a Heisenberg

state ket that does not evolve in time, we obtain the so-called Ehrenfest theorem [36]:

|

(3.47) |

When written in terms of expectation

values, this result is independent of whether we are using the Heisenberg or

Schrödinger picture. By contrast, the operator equation (3.46) only holds

if  and

and  are understood to be Heisenberg dynamical variables.

Note that Equation (3.47) has no dependence on

are understood to be Heisenberg dynamical variables.

Note that Equation (3.47) has no dependence on  .

In fact, it guarantees that the centroid of

a wavepacket always moves like a classical particle.

.

In fact, it guarantees that the centroid of

a wavepacket always moves like a classical particle.

Next: Schrödinger Wave Equation

Up: Quantum Dynamics

Previous: Heisenberg Equation of Motion

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-22

![]() (where

(where ![]() runs from 1 to 3), with three corresponding

conjugate momenta

runs from 1 to 3), with three corresponding

conjugate momenta ![]() . These are represented by three commuting position

operators

. These are represented by three commuting position

operators ![]() , and three commuting momentum operators

, and three commuting momentum operators ![]() , respectively. The

commutation

relations satisfied by the position and momentum operators

are

, respectively. The

commutation

relations satisfied by the position and momentum operators

are

![]() in the

Heisenberg picture. The Hamiltonian is assumed to have the same form as in

classical physics: that is,

in the

Heisenberg picture. The Hamiltonian is assumed to have the same form as in

classical physics: that is,

![$\displaystyle \frac{dp_i}{dt} = \frac{1}{{\rm i}\,\hbar}\,[p_i, H] = 0,$](img659.png)

![$\displaystyle \frac{d x_i}{dt} = \frac{1}{{\rm i}\,\hbar}\, [x_i, H] = \frac{1}...

... p_i}\! \left(\sum_{j=1,3} p_j^{\,2}\right) = \frac{p_i}{m} = \frac{p_i(0)}{m},$](img661.png)

![$\displaystyle x_i(t) = x_i(0) + \left[\frac{p_i(0)}{m}\right] t,$](img662.png)

![$\displaystyle [x_i(t), x_i(0)] = \left[ \frac{p_i(0)\,t}{m}, x_i(0)\right] = \frac{-{\rm i}\,\hbar \,t} {m}.$](img664.png)

![]() to our free particle Hamiltonian:

to our free particle Hamiltonian:

![$\displaystyle \frac{d p_i}{dt} = \frac{1}{{\rm i}\,\hbar} \,[p_i, V({\bf x})] = - \frac{\partial V({\bf x})}{\partial x_i},$](img670.png)