Next: Charged Particle Motion in

Up: Quantum Dynamics

Previous: Ehrenfest Theorem

Schrödinger Wave Equation

Consider the motion of a particle

in three dimensions in the Schrödinger picture. The fixed dynamical variables of

the system are the position operators,

, and the momentum operators,

, and the momentum operators,

.

The state of the system is represented as some time evolving ket

.

The state of the system is represented as some time evolving ket

.

.

Let

represent a simultaneous eigenket of the position operators

belonging to the eigenvalues

represent a simultaneous eigenket of the position operators

belonging to the eigenvalues

. Note that, because

the position operators are fixed in the Schrödinger picture, we do not

expect the

. Note that, because

the position operators are fixed in the Schrödinger picture, we do not

expect the

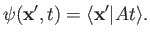

to evolve in time. The wavefunction of the system

at time

to evolve in time. The wavefunction of the system

at time  is defined

is defined

|

(3.48) |

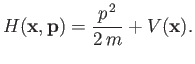

The Hamiltonian of the system is taken to be

|

(3.49) |

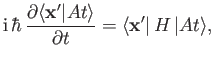

The Schrödinger equation of motion, (3.10), yields

|

(3.50) |

where use has been made of the time independence of the

.

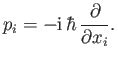

We adopt the Schrödinger representation in which the momentum conjugate

to the position operator

.

We adopt the Schrödinger representation in which the momentum conjugate

to the position operator  is written

is written

|

(3.51) |

[See Equation (2.74).]

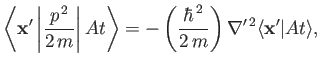

Thus,

|

(3.52) |

where use has been made of Equation (2.78). Here,

denotes the gradient operator written

in terms of the position eigenvalues. We can also

write

denotes the gradient operator written

in terms of the position eigenvalues. We can also

write

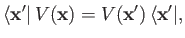

|

(3.53) |

where

is a scalar function of the position eigenvalues. Combining

Equations (3.49), (3.50), (3.52), and (3.53), we obtain

is a scalar function of the position eigenvalues. Combining

Equations (3.49), (3.50), (3.52), and (3.53), we obtain

|

(3.54) |

which can also be written

|

(3.55) |

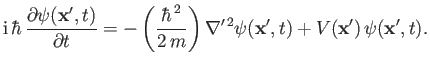

This is the Schrödinger time-dependent wave equation, and is the basis of

wave mechanics [99]. Note, however, that the wave equation is

just one of many possible representations of quantum mechanics. It just happens

to give a type of equation that we know how to solve. In deriving the wave equation, we have chosen to represent the system in terms of the eigenkets of

the position operators, instead of those of the momentum operators. We have

also fixed the relative phases of the

according to

the Schrödinger representation, so that Equation (3.51) is valid. Finally, we

have chosen to work in the Schrödinger picture, in which state kets evolve

and dynamical variables are fixed, instead of the Heisenberg picture,

in which the opposite is true.

according to

the Schrödinger representation, so that Equation (3.51) is valid. Finally, we

have chosen to work in the Schrödinger picture, in which state kets evolve

and dynamical variables are fixed, instead of the Heisenberg picture,

in which the opposite is true.

Suppose that the ket

is an eigenket of the Hamiltonian

belonging to the eigenvalue

is an eigenket of the Hamiltonian

belonging to the eigenvalue  : that is,

: that is,

|

(3.56) |

The Schrödinger equation of motion, (3.10), yields

|

(3.57) |

This can be integrated to give

![$\displaystyle \vert At\rangle = \exp\left[\frac{ -{\rm i}\,H'(t-t_0)}{\hbar}\right]\, \vert At_0\rangle.$](img692.png) |

(3.58) |

Note that

only differs from

only differs from

by a phase-factor. The direction of the vector remains fixed in ket space. This

suggests that if the system is initially in an eigenstate of the

Hamiltonian then it remains in this state for ever, as long as the system

is undisturbed. Such a state is called a stationary state. The wavefunction

of a stationary state satisfies

by a phase-factor. The direction of the vector remains fixed in ket space. This

suggests that if the system is initially in an eigenstate of the

Hamiltonian then it remains in this state for ever, as long as the system

is undisturbed. Such a state is called a stationary state. The wavefunction

of a stationary state satisfies

![$\displaystyle \psi({\bf x}', t) = \exp\left[\frac{ -{\rm i}\,H'\,(t-t_0)}{\hbar}\right]\psi({\bf x'}, t_0).$](img693.png) |

(3.59) |

Substituting the previous relation into the Schrödinger time-dependent wave equation,

(3.55), we

obtain

![$\displaystyle -\left(\frac{\hbar^{\,2}}{2\,m}\right)\nabla'^{\,2}\psi_0({\bf x'}) + [V({\bf x'})-E]\,\psi_0({\bf x'}) =0,$](img694.png) |

(3.60) |

where

,

and

,

and  is the energy of the system. This is the Schrödinger time-independent

wave equation. A bound state solution of the

previous equation, in which the particle is confined within a finite region

of space, satisfies the boundary condition

is the energy of the system. This is the Schrödinger time-independent

wave equation. A bound state solution of the

previous equation, in which the particle is confined within a finite region

of space, satisfies the boundary condition

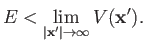

Such a solution is only possible if

|

(3.62) |

Because it is conventional to set the potential at infinity equal to zero, the previous

relation implies that bound states are equivalent to negative energy states [50].

The boundary condition (3.61) is sufficient to uniquely specify the solution

of Equation (3.60).

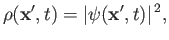

The quantity

, defined by

, defined by

|

(3.63) |

is termed the probability density. Recall, from a direct generalization of Equation (2.30), that the

probability of observing the particle in some volume element

around position

around position  is proportional to

is proportional to

.

The probability is equal to

.

The probability is equal to

if the wavefunction

is properly normalized, so that

if the wavefunction

is properly normalized, so that

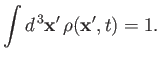

|

(3.64) |

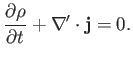

The Schrödinger time-dependent wave equation, (3.55), can easily be

transformed into a conservation equation for the probability

density:

|

(3.65) |

The probability

current,  , takes the form

, takes the form

![$\displaystyle {\bf j}({\bf x}', t) = - \left(\frac{{\rm i}\, \hbar}{2\,m}\right...

...\psi\right] = \left(\frac{\hbar}{m} \right){\rm Im} (\psi^\ast \,\nabla' \psi).$](img709.png) |

(3.66) |

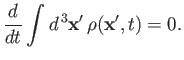

We can integrate Equation (3.65) over all space, using the divergence theorem [92],

and the boundary condition

as

as

, to obtain

, to obtain

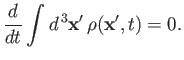

|

(3.67) |

Thus, the Schrödinger time-dependent wave equation conserves

probability. In particular, if the

wavefunction starts off properly normalized, according to Equation (3.64), then it

remains properly normalized at all subsequent times. It is easily

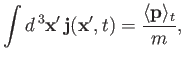

demonstrated that

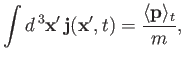

|

(3.68) |

where

denotes the expectation value of the momentum

evaluated at time

denotes the expectation value of the momentum

evaluated at time  . Clearly, the probability current is indirectly related to

the particle momentum.

. Clearly, the probability current is indirectly related to

the particle momentum.

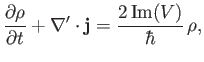

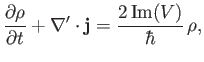

In deriving Equations (3.65), we have, naturally, assumed that the potential

is real. Suppose, however, that the potential has an imaginary component.

In this case, Equation (3.65) generalizes to

is real. Suppose, however, that the potential has an imaginary component.

In this case, Equation (3.65) generalizes to

|

(3.69) |

giving

![$\displaystyle \frac{d}{dt} \int d^{\,3} {\bf x}'\,\rho({\bf x'}, t) = \frac{2}{\hbar} \int d^{\,3} {\bf x}'\,{\rm Im}[V({\bf x}')] \,\rho({\bf x'}, t).$](img717.png) |

(3.70) |

(See Exercise 2.)

Thus, if

then the total probability of observing the particle

anywhere in space

decreases monotonically with time. Hence, an imaginary potential can be

used to account for the disappearance or decay of a particle. Such a potential

is often employed to model nuclear reactions in which incident particles are

absorbed by nuclei.

then the total probability of observing the particle

anywhere in space

decreases monotonically with time. Hence, an imaginary potential can be

used to account for the disappearance or decay of a particle. Such a potential

is often employed to model nuclear reactions in which incident particles are

absorbed by nuclei.

Next: Charged Particle Motion in

Up: Quantum Dynamics

Previous: Ehrenfest Theorem

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-22

![]() represent a simultaneous eigenket of the position operators

belonging to the eigenvalues

represent a simultaneous eigenket of the position operators

belonging to the eigenvalues

![]() . Note that, because

the position operators are fixed in the Schrödinger picture, we do not

expect the

. Note that, because

the position operators are fixed in the Schrödinger picture, we do not

expect the

![]() to evolve in time. The wavefunction of the system

at time

to evolve in time. The wavefunction of the system

at time ![]() is defined

is defined

![]() is an eigenket of the Hamiltonian

belonging to the eigenvalue

is an eigenket of the Hamiltonian

belonging to the eigenvalue ![]() : that is,

: that is,

![$\displaystyle \vert At\rangle = \exp\left[\frac{ -{\rm i}\,H'(t-t_0)}{\hbar}\right]\, \vert At_0\rangle.$](img692.png)

![$\displaystyle \psi({\bf x}', t) = \exp\left[\frac{ -{\rm i}\,H'\,(t-t_0)}{\hbar}\right]\psi({\bf x'}, t_0).$](img693.png)

![]() , defined by

, defined by

![]() is real. Suppose, however, that the potential has an imaginary component.

In this case, Equation (3.65) generalizes to

is real. Suppose, however, that the potential has an imaginary component.

In this case, Equation (3.65) generalizes to

![$\displaystyle \frac{d}{dt} \int d^{\,3} {\bf x}'\,\rho({\bf x'}, t) = \frac{2}{\hbar} \int d^{\,3} {\bf x}'\,{\rm Im}[V({\bf x}')] \,\rho({\bf x'}, t).$](img717.png)