Next: Potential due to uniform Up: Newtonian gravity Previous: Potential due to uniform

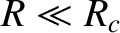

and mean radius

and mean radius  . A spheroid is

the solid body produced by rotating an ellipse about a major or

a minor axis. Let the axis of rotation coincide with the

. A spheroid is

the solid body produced by rotating an ellipse about a major or

a minor axis. Let the axis of rotation coincide with the  -axis,

and let the outer boundary of the spheroid satisfy

where

-axis,

and let the outer boundary of the spheroid satisfy

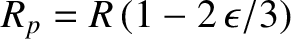

where  is termed the ellipticity. In fact, the radius of the

spheroid at the poles (i.e., along the rotation axis) is

is termed the ellipticity. In fact, the radius of the

spheroid at the poles (i.e., along the rotation axis) is

, whereas

the radius at the equator (i.e., in the bisecting plane perpendicular to the axis) is

, whereas

the radius at the equator (i.e., in the bisecting plane perpendicular to the axis) is

. Hence,

. Hence,

|

(3.57) |

, so that the spheroid is very close to being a

sphere. If

, so that the spheroid is very close to being a

sphere. If

then the spheroid is

slightly squashed along its symmetry axis and is termed oblate. Likewise, if

then the spheroid is

slightly squashed along its symmetry axis and is termed oblate. Likewise, if

then the spheroid is slightly elongated along its axis and is

termed prolate. See Figure 3.1.

Of course, if

then the spheroid is slightly elongated along its axis and is

termed prolate. See Figure 3.1.

Of course, if

then the spheroid reduces to a sphere.

then the spheroid reduces to a sphere.

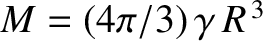

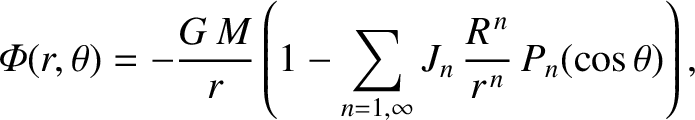

Now, according to Equation (3.45) and (3.46), the gravitational potential generated outside an axially symmetric mass distribution can be written

where is the total mass of the distribution, and

Here, the integral is taken over the whole cross section of the distribution

in

is the total mass of the distribution, and

Here, the integral is taken over the whole cross section of the distribution

in  -

- space.

space.

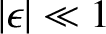

It follows that for a uniform spheroid, for which

,

,

![$\displaystyle J_n = -\frac{3}{2\,(3+n)}\int_0^\pi P_n(\cos\theta)\left[\frac{R_\theta(\theta)}{R}\right]^{3+n}\,\sin\theta\,d\theta,$](img477.png) |

(3.61) |

![$\displaystyle J_n \simeq -\frac{3}{2\,(3+n)}\int_0^\pi P_n(\cos\theta)\left[P_0...

...theta)-\frac{2}{3}\,(3+n)\,\epsilon\,P_2(\cos\theta)\right]\sin\theta\,d\theta,$](img478.png) |

(3.62) |

. It is thus clear, from Equation (3.42),

that, to first order in

. It is thus clear, from Equation (3.42),

that, to first order in  , the only nonzero

, the only nonzero  are

Thus, the gravitational potential outside a uniform spheroid of

total mass

are

Thus, the gravitational potential outside a uniform spheroid of

total mass  , mean radius

, mean radius  , and ellipticity

, and ellipticity  is

is

By analogy with the preceding analysis, the gravitational potential outside a general (i.e., axisymmetric, but not necessarily uniform) spheroidal

mass distribution of mass  , mean radius

, mean radius  , and ellipticity

, and ellipticity  (where

(where

) can be written

) can be written

.

In particular,

the gravitational potential on the surface of the spheroid is

.

In particular,

the gravitational potential on the surface of the spheroid is

|

(3.67) |

[see Equation (3.64)], the preceding expression

simplifies to

[see Equation (3.64)], the preceding expression

simplifies to

Consider a self-gravitating spheroid of mass  , mean radius

, mean radius  , and ellipticity

, and ellipticity  , such as a star or a planet. Assuming, for the sake of simplicity, that the

spheroid is composed of uniform-density incompressible fluid, it follows that the gravitational potential on its surface is

given by Equation (3.69). However, the condition for an equilibrium

state is that the potential be constant over the surface. If this is not

the case then there will be gravitational forces acting tangential to the

surface. Such forces cannot be balanced by internal fluid pressure, which only

acts normal to the surface. Hence, from Equation (3.69), it is clear that the

condition for equilibrium is

, such as a star or a planet. Assuming, for the sake of simplicity, that the

spheroid is composed of uniform-density incompressible fluid, it follows that the gravitational potential on its surface is

given by Equation (3.69). However, the condition for an equilibrium

state is that the potential be constant over the surface. If this is not

the case then there will be gravitational forces acting tangential to the

surface. Such forces cannot be balanced by internal fluid pressure, which only

acts normal to the surface. Hence, from Equation (3.69), it is clear that the

condition for equilibrium is

. In other words, the equilibrium

configuration of a uniform-density, self-gravitating, fluid, mass distribution is a sphere. Deviations

from this configuration can only be caused by forces in addition to self-gravity

and internal fluid pressure; for instance, internal tensile forces, centrifugal forces due to rotation, and tidal

forces due to orbiting masses. (See Chapter 6.) The same is true for a self-gravitating mass distribution of non-uniform

density.

. In other words, the equilibrium

configuration of a uniform-density, self-gravitating, fluid, mass distribution is a sphere. Deviations

from this configuration can only be caused by forces in addition to self-gravity

and internal fluid pressure; for instance, internal tensile forces, centrifugal forces due to rotation, and tidal

forces due to orbiting masses. (See Chapter 6.) The same is true for a self-gravitating mass distribution of non-uniform

density.

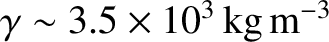

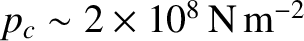

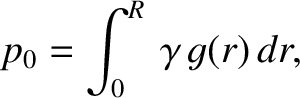

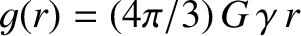

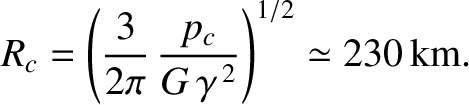

We can estimate how small a rocky asteroid, say, needs to be before its material strength is sufficient

to allow it to retain a significantly non-spherical shape. The typical density of rocky asteroids in the solar system is

. Moreover, the critical pressure above which the rock

out of which such asteroids are composed ceases to act like a rigid material, and instead deforms and flows like a liquid, is

. Moreover, the critical pressure above which the rock

out of which such asteroids are composed ceases to act like a rigid material, and instead deforms and flows like a liquid, is

(de Pater and Lissauer 2010).

We must compare this critical pressure with the pressure at the center of the asteroid. Assuming, for the

sake of simplicity, that the asteroid is roughly spherical, of radius

(de Pater and Lissauer 2010).

We must compare this critical pressure with the pressure at the center of the asteroid. Assuming, for the

sake of simplicity, that the asteroid is roughly spherical, of radius  , and of uniform density

, and of uniform density  , the central

pressure is

, the central

pressure is

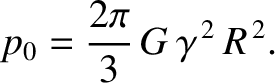

|

(3.70) |

is the gravitational acceleration at radius

is the gravitational acceleration at radius  . [See Equation (3.53).] This result is a simple generalization

of the well-known formula

. [See Equation (3.53).] This result is a simple generalization

of the well-known formula

for the pressure a depth

for the pressure a depth  below the surface of a fluid. It follows that

below the surface of a fluid. It follows that

|

(3.71) |

then the internal pressure in the asteroid is not sufficiently high to cause its constituent rock

to deform like a liquid. Such an asteroid can therefore retain a significantly

non-spherical shape. On the other hand, if

then the internal pressure in the asteroid is not sufficiently high to cause its constituent rock

to deform like a liquid. Such an asteroid can therefore retain a significantly

non-spherical shape. On the other hand, if

then the internal pressure is large enough

to render the asteroid fluid-like. Such an asteroid cannot withstand the tendency of

self-gravity to make it adopt a spherical shape. The same applies to any rocky body in the solar system. The condition

then the internal pressure is large enough

to render the asteroid fluid-like. Such an asteroid cannot withstand the tendency of

self-gravity to make it adopt a spherical shape. The same applies to any rocky body in the solar system. The condition

is

equivalent to

is

equivalent to  , where

, where

|

(3.72) |

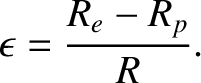

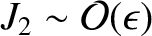

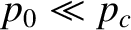

—for instance,

the two moons of Mars, Phobos (see Figure 3.2) and Deimos—can retain a highly non-spherical

shape. On the other hand, a rocky body whose radius is significantly greater than about

—for instance,

the two moons of Mars, Phobos (see Figure 3.2) and Deimos—can retain a highly non-spherical

shape. On the other hand, a rocky body whose radius is significantly greater than about

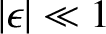

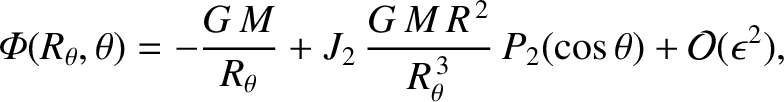

—for instance,

the asteroid Ceres (see Figure 3.3) and the Earth's moon—is forced by gravity to be essentially spherical.

—for instance,

the asteroid Ceres (see Figure 3.3) and the Earth's moon—is forced by gravity to be essentially spherical.

![\includegraphics[height=2.25in]{Chapter02/fig2_02.eps}](img504.png) |

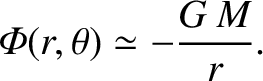

According to Equations (3.58) and (3.63) , the gravitational potential outside a general axisymmetric body of mass  and mean radius

and mean radius  can be written

can be written

|

(3.73) |

are

are

(or smaller) dimensionless parameters that depend on the exact shape of the body. However,

a long way from the body (i.e.,

(or smaller) dimensionless parameters that depend on the exact shape of the body. However,

a long way from the body (i.e.,  ), the right-hand side of the preceding expression is clearly dominated by the first term inside the round

brackets, so that

), the right-hand side of the preceding expression is clearly dominated by the first term inside the round

brackets, so that

|

(3.74) |

![\includegraphics[height=2.25in]{Chapter02/fig2_03.eps}](img510.png) |