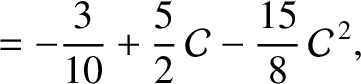

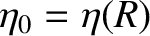

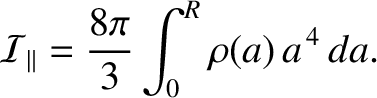

To lowest order in  , the moment of inertia of our body about its rotation axis can be written

, the moment of inertia of our body about its rotation axis can be written

|

(D.43) |

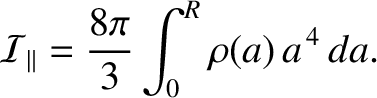

It follows from Equation (D.27) that

![$\displaystyle {\cal I}_\parallel =\frac{8\pi}{9}\int_0^R \left(3\,\bar{\rho}\,a...

...\pi}{9}\left[\bar{\rho}(R)\,R^{\,5}-2\int_0^R\bar{\rho}(a)\,a^{\,4}\,da\right],$](img4397.png) |

(D.44) |

|

(D.45) |

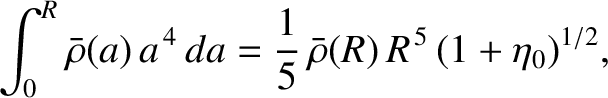

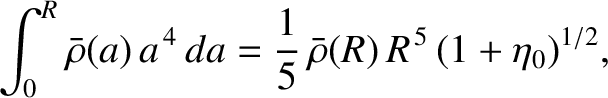

where

. Hence, we obtain

. Hence, we obtain

![$\displaystyle {\cal I}_\parallel = \frac{8\pi}{9}\,\bar{\rho}(R)\,R^{\,5}\left[1-\frac{2}{5}\,(1+\eta_0)^{1/2}\right].$](img4400.png) |

(D.46) |

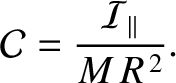

It is convenient to define the dimensionless moment of inertia

|

(D.47) |

Making use of Equations (D.29) and (D.46), we deduce that

![$\displaystyle {\cal C} =\frac{2}{3}\left[1-\frac{2}{5}\,(1+\eta_0)^{1/2}\right].$](img4402.png) |

(D.48) |

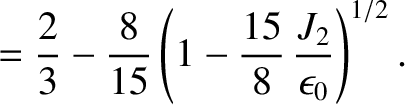

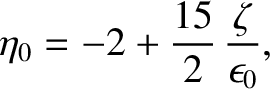

However, Equation (D.31) yields

|

(D.49) |

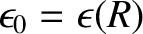

where

. Hence, we obtain the so-called Darwin-Radau equation (Radau 1885; Darwin 1899),

. Hence, we obtain the so-called Darwin-Radau equation (Radau 1885; Darwin 1899),

![$\displaystyle {\cal C} =\frac{2}{3}\left[1-\frac{2}{5}\left(\frac{15}{2}\,\frac{\zeta}{\epsilon_0}-1\right)^{1/2}\right].$](img4405.png) |

(D.50) |

This equation relates the degree of flattening of an inhomogeneous rotating body to its rotational angular velocity and its

moment of inertia about its rotation axis. The Darwin-Radau equation is only valid if the response of the body to the

centrifugal potential is fluid-like. Recall, also, that the equation was derived under the assumption that the rotation is sufficiently slow that

and

and  can both be treated as small parameters, and, in particular, that any quantities that are second order, or higher, in these parameters

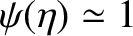

can be neglected in the analysis. Note, finally, that the derivation of the Darwin-Radau equation depends crucially on the approximation

can both be treated as small parameters, and, in particular, that any quantities that are second order, or higher, in these parameters

can be neglected in the analysis. Note, finally, that the derivation of the Darwin-Radau equation depends crucially on the approximation

, where

, where

is defined in Equation (D.40).

is defined in Equation (D.40).

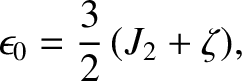

For a rotating body in hydrostatic equilibrium (in the co-rotating frame), Equation (6.43) yields

|

(D.51) |

where  is the body's dimensionless gravitational quadrupole moment. [See Equation (8.86).]

The previous two equations can be combined to give the following alternative versions of the Darwin-Radau equation:

is the body's dimensionless gravitational quadrupole moment. [See Equation (8.86).]

The previous two equations can be combined to give the following alternative versions of the Darwin-Radau equation:

, the moment of inertia of our body about its rotation axis can be written

, the moment of inertia of our body about its rotation axis can be written

![$\displaystyle {\cal I}_\parallel =\frac{8\pi}{9}\int_0^R \left(3\,\bar{\rho}\,a...

...\pi}{9}\left[\bar{\rho}(R)\,R^{\,5}-2\int_0^R\bar{\rho}(a)\,a^{\,4}\,da\right],$](img4397.png)

. Hence, we obtain

It is convenient to define the dimensionless moment of inertia

. Hence, we obtain

It is convenient to define the dimensionless moment of inertia

. Hence, we obtain the so-called Darwin-Radau equation (Radau 1885; Darwin 1899),

. Hence, we obtain the so-called Darwin-Radau equation (Radau 1885; Darwin 1899),

![$\displaystyle {\cal C} =\frac{2}{3}\left[1-\frac{2}{5}\left(\frac{15}{2}\,\frac{\zeta}{\epsilon_0}-1\right)^{1/2}\right].$](img4405.png)

and

and  can both be treated as small parameters, and, in particular, that any quantities that are second order, or higher, in these parameters

can be neglected in the analysis. Note, finally, that the derivation of the Darwin-Radau equation depends crucially on the approximation

can both be treated as small parameters, and, in particular, that any quantities that are second order, or higher, in these parameters

can be neglected in the analysis. Note, finally, that the derivation of the Darwin-Radau equation depends crucially on the approximation

, where

, where

is defined in Equation (D.40).

is defined in Equation (D.40).

is the body's dimensionless gravitational quadrupole moment. [See Equation (8.86).]

The previous two equations can be combined to give the following alternative versions of the Darwin-Radau equation:

is the body's dimensionless gravitational quadrupole moment. [See Equation (8.86).]

The previous two equations can be combined to give the following alternative versions of the Darwin-Radau equation: