Next: Tidal Elongation of Earth Up: Spheroidal Mass Distributions Previous: Two-Body Dynamics

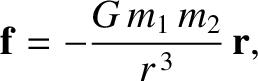

In a binary star system, the gravitational force that the first star exerts on the second is

|

(1.439) |

. [See Equation (1.238).]

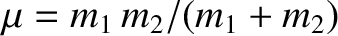

As we have seen, a two-body system can be reduced to an equivalent

one-body system whose equation of motion is of the form (1.437),

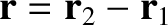

where

. [See Equation (1.238).]

As we have seen, a two-body system can be reduced to an equivalent

one-body system whose equation of motion is of the form (1.437),

where

.

Hence, in this particular case, we can write

.

Hence, in this particular case, we can write

|

(1.440) |

|

(1.442) |

Equation (1.441) is identical to Equation (1.277), which we have already solved. Hence, we can immediately write down the solution (see Sections 1.9.5–1.9.7):

|

(1.443) |

|

(1.444) |

|

(1.445) |

|

(1.446) |

is a constant, and we have aligned our Cartesian axes so that the plane of the orbit

coincides with the

is a constant, and we have aligned our Cartesian axes so that the plane of the orbit

coincides with the  -

- plane.

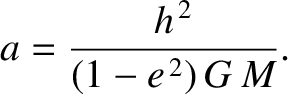

According to the previous solution, the second star executes a Keplerian

elliptical orbit, with major radius

plane.

According to the previous solution, the second star executes a Keplerian

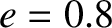

elliptical orbit, with major radius  and eccentricity

and eccentricity  ,

relative to the first star, and vice versa. From Equation (1.323), the period of revolution,

,

relative to the first star, and vice versa. From Equation (1.323), the period of revolution,  , is given by

, is given by

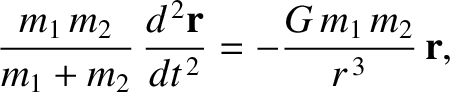

In the inertial frame of reference whose origin always coincides with the center of mass—the so-called center of mass frame—the displacement of the two stars are

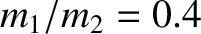

where was specified previously. Figure 1.23 shows an example binary star orbit, in the center of mass frame, calculated with

was specified previously. Figure 1.23 shows an example binary star orbit, in the center of mass frame, calculated with

and

and  . It can be seen that both stars execute

elliptical orbits about their common center of mass. Furthermore, at any given point in time, the stars are diagrammatically opposite one another, relative to the center of mass.

. It can be seen that both stars execute

elliptical orbits about their common center of mass. Furthermore, at any given point in time, the stars are diagrammatically opposite one another, relative to the center of mass.

Binary star systems have been very useful to astronomers, because it is

possible to determine the masses of both stars in such a system

by careful observation.

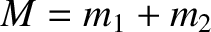

The sum of the masses of the two stars,  , can be found

from Equation (1.447) after a measurement of the major radius,

, can be found

from Equation (1.447) after a measurement of the major radius,  (which

is the mean of the greatest and smallest distance apart of the two

stars during their orbit), and the orbital period,

(which

is the mean of the greatest and smallest distance apart of the two

stars during their orbit), and the orbital period,  . The ratio of the

masses of the two stars,

. The ratio of the

masses of the two stars,  , can be determined from Equations (1.448) and (1.449) by

observing the fixed ratio of the relative distances of the two stars from the common

center of mass about which they both appear to rotate. Obviously, given the sum

of the masses, and the ratio of the masses, the individual masses themselves can

then be calculated.

, can be determined from Equations (1.448) and (1.449) by

observing the fixed ratio of the relative distances of the two stars from the common

center of mass about which they both appear to rotate. Obviously, given the sum

of the masses, and the ratio of the masses, the individual masses themselves can

then be calculated.