Next: Motion of a Submerged

Up: Two-Dimensional Incompressible Inviscid Flow

Previous: Two-Dimensional Irrotational Flow in

Flow Past a Cylindrical Obstacle

Consider the steady flow pattern produced when an impenetrable rigid cylindrical obstacle is placed in a uniformly flowing,

incompressible, inviscid fluid, with the cylinder orientated such that its axis is normal to the flow. For instance, suppose that the radius of the cylinder is

, and that its axis corresponds to the line

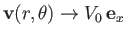

, and that its axis corresponds to the line  . Furthermore, let the unperturbed fluid velocity be of magnitude

. Furthermore, let the unperturbed fluid velocity be of magnitude  , and

be directed parallel to the

, and

be directed parallel to the  -axis. We expect the

flow pattern to remain unperturbed very far away from the cylinder. In other words,

we expect

-axis. We expect the

flow pattern to remain unperturbed very far away from the cylinder. In other words,

we expect

as

as

,

which corresponds to a boundary condition on the stream function of the form (see Section 5.4)

,

which corresponds to a boundary condition on the stream function of the form (see Section 5.4)

Given that the fluid velocity field a large distance upstream of the cylinder is irrotational (because we

have already seen that the flow pattern associated with uniform

flow is irrotational--see Section 5.4), it follows from the Kelvin circulation theorem (see Section 4.14)

that the velocity field remains irrotational as it is convected past the cylinder. Hence, according to Section 5.2, the stream function of the

flow satisfies Laplace's equation,

|

(5.71) |

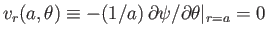

The appropriate boundary condition at the surface of the cylinder is simply that the normal fluid

velocity there be zero, because the fluid must stay in contact with the cylinder, but cannot penetrate its

surface. Hence,

, which implies that

, which implies that

|

(5.72) |

because  is undetermined to an arbitrary additive constant. It follows that we are searching for the most

general solution of Equation (5.71) that satisfies the boundary conditions (5.70) and (5.72).

Comparison with Equation (5.66) reveals that this solution takes the form

is undetermined to an arbitrary additive constant. It follows that we are searching for the most

general solution of Equation (5.71) that satisfies the boundary conditions (5.70) and (5.72).

Comparison with Equation (5.66) reveals that this solution takes the form

![$\displaystyle \psi(r,\theta) = V_0\,a\left[-\gamma\,\ln\left(\frac{r}{a}\right)-\left(\frac{r}{a}-\frac{a}{r}\right)\sin\theta\right],$](img1768.png) |

(5.73) |

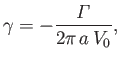

where

|

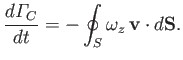

(5.74) |

and

is the circulation of the flow around the cylinder.

(Note that the velocity field can be irrotational, but still possess nonzero circulation

around the cylinder, because a loop that encloses the cylinder cannot be spanned

by a surface lying entirely within the fluid. Thus, zero fluid vorticity does not

necessarily imply zero circulation around such a loop from the curl theorem.) Let us assume that

is the circulation of the flow around the cylinder.

(Note that the velocity field can be irrotational, but still possess nonzero circulation

around the cylinder, because a loop that encloses the cylinder cannot be spanned

by a surface lying entirely within the fluid. Thus, zero fluid vorticity does not

necessarily imply zero circulation around such a loop from the curl theorem.) Let us assume that

, for the

sake of definiteness.

, for the

sake of definiteness.

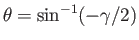

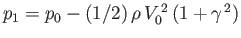

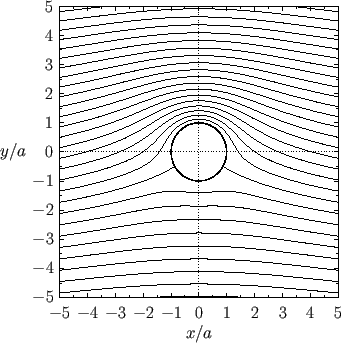

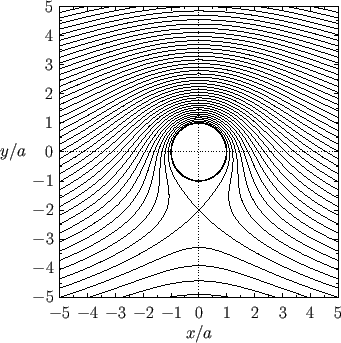

Figure 5.6-5.8 show streamlines of the flow calculated for various different values of the normalized circulation,

. For

. For  , there exist a pair of points on the surface of the

cylinder at which the flow speed is zero. These are known as stagnation points, and can be located in Figures 5.6

and 5.7 as the points at which streamlines intersect the surface of the cylinder at right-angles. The

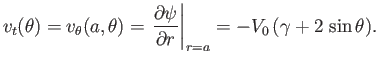

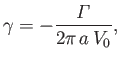

tangential fluid velocity at the surface of the cylinder is

, there exist a pair of points on the surface of the

cylinder at which the flow speed is zero. These are known as stagnation points, and can be located in Figures 5.6

and 5.7 as the points at which streamlines intersect the surface of the cylinder at right-angles. The

tangential fluid velocity at the surface of the cylinder is

|

(5.75) |

The stagnation points correspond to the points at which  (because the normal velocity is automatically

zero at the surface of the cylinder). Thus, the stagnation points lie at

(because the normal velocity is automatically

zero at the surface of the cylinder). Thus, the stagnation points lie at

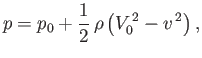

. When

. When  ,

the stagnation points coalesce and move off the surface of the cylinder, as illustrated in Figure 5.8 (the stagnation point

corresponds to the point at which two streamlines cross at right-angles).

,

the stagnation points coalesce and move off the surface of the cylinder, as illustrated in Figure 5.8 (the stagnation point

corresponds to the point at which two streamlines cross at right-angles).

Figure:

Streamlines of the flow generated by a cylindrical obstacle of radius  , whose axis runs along the

, whose axis runs along the  -axis,

placed in the uniform flow field

-axis,

placed in the uniform flow field

. The normalized circulation is

. The normalized circulation is  .

.

|

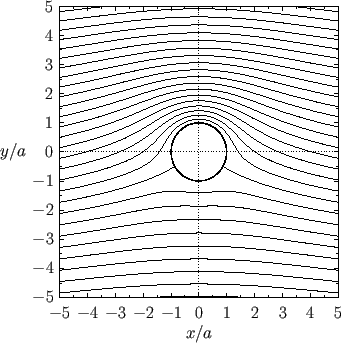

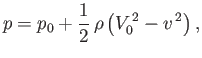

The irrotational form of Bernoulli's theorem, (4.97), can be combined with the boundary condition

as

as

, as well as the fact that

, as well as the fact that

is constant in the present case, to give

is constant in the present case, to give

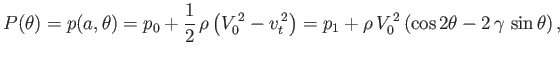

|

(5.76) |

where  is the constant static fluid pressure a large distance from the cylinder. In particular, the fluid

pressure on the surface of the cylinder is

is the constant static fluid pressure a large distance from the cylinder. In particular, the fluid

pressure on the surface of the cylinder is

|

(5.77) |

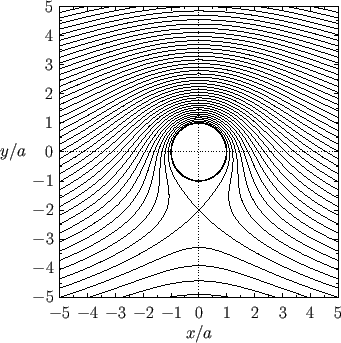

where

.

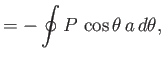

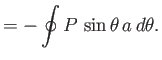

The net force per unit length exerted on the cylinder by the fluid has the Cartesian coordinates

.

The net force per unit length exerted on the cylinder by the fluid has the Cartesian coordinates

Thus, it follows from Equation (5.77) that

The component of the force that a moving fluid exerts on an obstacle, placed in its path, in a direction parallel to that of the unperturbed flow is usually called drag. On the other hand, the component of the force that

the fluid exerts in a direction perpendicular to that of the unperturbed flow is usually called lift. Hence, the previous equations imply

that if a cylindrical obstacle is placed in a uniformly flowing inviscid fluid then there is zero drag. On the other

hand, as long as there is net circulation of the flow around the cylinder, the lift is non-zero. Lift is generated because (negative)

circulation tends to increase the fluid speed directly above, and to decrease it directly below, the cylinder.

Thus, from Bernoulli's theorem, the fluid pressure is decreased above, and increased below,

the cylinder, giving rise to a net upward force (i.e., a force in the  -direction).

-direction).

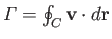

Figure:

Streamlines of the flow generated by a cylindrical obstacle of radius  , whose axis runs along the

, whose axis runs along the  -axis,

placed in the uniform flow field

-axis,

placed in the uniform flow field

. The normalized circulation is

. The normalized circulation is

.

.

|

Suppose that the cylinder is placed in a fluid which is initially at rest, and that the fluid's uniform flow velocity,  ,

is then very slowly ramped up (in such a manner that no vorticity is induced in the upstream flow at infinity). Because the flow pattern is initially irrotational, and because the

flow pattern well upstream of the cylinder is assumed to remain irrotational, the Kelvin circulation theorem indicates

that the flow pattern around the cylinder also remains irrotational. Consider the time evolution of the circulation,

,

is then very slowly ramped up (in such a manner that no vorticity is induced in the upstream flow at infinity). Because the flow pattern is initially irrotational, and because the

flow pattern well upstream of the cylinder is assumed to remain irrotational, the Kelvin circulation theorem indicates

that the flow pattern around the cylinder also remains irrotational. Consider the time evolution of the circulation,

, around

some fixed curve

, around

some fixed curve  that lies entirely within the fluid, and encloses the cylinder. We have

that lies entirely within the fluid, and encloses the cylinder. We have

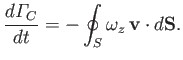

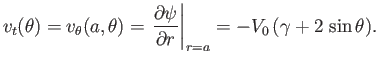

![$\displaystyle \frac{d{\mit\Gamma}_C}{dt} = \oint_C\frac{\partial {\bf v}}{\part...

...t]\cdot d{\bf r}= \oint_C {\bf v}\times \mbox{\boldmath$\omega$}\cdot d{\bf r},$](img1789.png) |

(5.82) |

where use has been made of Equation (4.84) (with

assumed constant). However,

assumed constant). However,

in two-dimensional flow, and

in two-dimensional flow, and

, where

, where  is an outward surface element of a unit depth (in the

is an outward surface element of a unit depth (in the  -direction)

surface whose normal lies in the

-direction)

surface whose normal lies in the  -

- plane, and that cuts the

plane, and that cuts the  -

- plane at

plane at  . In other words,

. In other words,

|

(5.83) |

We, thus, conclude that the rate of change of the circulation around  is equal to minus the flux of the vorticity across

is equal to minus the flux of the vorticity across  [assuming that vorticity is convected by the flow, which follows from Equation (4.85), the fact that

[assuming that vorticity is convected by the flow, which follows from Equation (4.85), the fact that

, and the fact that

, and the fact that

in two-dimensional flow].

However, we have already seen that the flow field surrounding the cylinder is irrotational (i.e., such that

in two-dimensional flow].

However, we have already seen that the flow field surrounding the cylinder is irrotational (i.e., such that

). It follows that

). It follows that

is constant in time. Moreover, because

is constant in time. Moreover, because

originally, as the fluid surrounding the cylinder was initially

at rest, we deduce that

originally, as the fluid surrounding the cylinder was initially

at rest, we deduce that

at all subsequent times. Hence, we conclude that, in an inviscid fluid,

if the circulation of the flow around the cylinder is initially zero then it remains zero. It follows, from the previous

analysis, that, in such a fluid, zero drag force and zero lift force are exerted on the cylinder as a consequence of the

fluid flow. This result is a manifestation of d'Alembert's paradox, which was introduced in Section 4.5. d'Alembert's result is paradoxical because it would seem, at

first sight, to be a reasonable approximation to neglect viscosity altogether in high Reynolds number flow. However, if

we do this then we end up with the nonsensical prediction that a high Reynolds number fluid is incapable of

exerting any force on an obstacle placed in its path.

at all subsequent times. Hence, we conclude that, in an inviscid fluid,

if the circulation of the flow around the cylinder is initially zero then it remains zero. It follows, from the previous

analysis, that, in such a fluid, zero drag force and zero lift force are exerted on the cylinder as a consequence of the

fluid flow. This result is a manifestation of d'Alembert's paradox, which was introduced in Section 4.5. d'Alembert's result is paradoxical because it would seem, at

first sight, to be a reasonable approximation to neglect viscosity altogether in high Reynolds number flow. However, if

we do this then we end up with the nonsensical prediction that a high Reynolds number fluid is incapable of

exerting any force on an obstacle placed in its path.

Next: Motion of a Submerged

Up: Two-Dimensional Incompressible Inviscid Flow

Previous: Two-Dimensional Irrotational Flow in

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-03-31

![$\displaystyle \psi(r,\theta) = V_0\,a\left[-\gamma\,\ln\left(\frac{r}{a}\right)-\left(\frac{r}{a}-\frac{a}{r}\right)\sin\theta\right],$](img1768.png)

![]() . For

. For ![]() , there exist a pair of points on the surface of the

cylinder at which the flow speed is zero. These are known as stagnation points, and can be located in Figures 5.6

and 5.7 as the points at which streamlines intersect the surface of the cylinder at right-angles. The

tangential fluid velocity at the surface of the cylinder is

, there exist a pair of points on the surface of the

cylinder at which the flow speed is zero. These are known as stagnation points, and can be located in Figures 5.6

and 5.7 as the points at which streamlines intersect the surface of the cylinder at right-angles. The

tangential fluid velocity at the surface of the cylinder is

![]() as

as

![]() , as well as the fact that

, as well as the fact that

![]() is constant in the present case, to give

is constant in the present case, to give

![]() ,

is then very slowly ramped up (in such a manner that no vorticity is induced in the upstream flow at infinity). Because the flow pattern is initially irrotational, and because the

flow pattern well upstream of the cylinder is assumed to remain irrotational, the Kelvin circulation theorem indicates

that the flow pattern around the cylinder also remains irrotational. Consider the time evolution of the circulation,

,

is then very slowly ramped up (in such a manner that no vorticity is induced in the upstream flow at infinity). Because the flow pattern is initially irrotational, and because the

flow pattern well upstream of the cylinder is assumed to remain irrotational, the Kelvin circulation theorem indicates

that the flow pattern around the cylinder also remains irrotational. Consider the time evolution of the circulation,

![]() , around

some fixed curve

, around

some fixed curve ![]() that lies entirely within the fluid, and encloses the cylinder. We have

that lies entirely within the fluid, and encloses the cylinder. We have

![$\displaystyle \frac{d{\mit\Gamma}_C}{dt} = \oint_C\frac{\partial {\bf v}}{\part...

...t]\cdot d{\bf r}= \oint_C {\bf v}\times \mbox{\boldmath$\omega$}\cdot d{\bf r},$](img1789.png)