Next: Exercises

Up: Incompressible Inviscid Flow

Previous: Kelvin Circulation Theorem

Irrotational Flow

Flow is said to be irrotational when the vorticity

has the magnitude zero everywhere.

It immediately follows, from Equation (4.77), that the circulation around any arbitrary loop in an irrotational

flow pattern is zero (provided that the loop can be spanned by a surface that lies entirely within the fluid). Hence, from Kelvin's circulation theorem, if an inviscid fluid is initially irrotational

then it remains irrotational at all subsequent times. This can be seen more directly from the

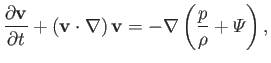

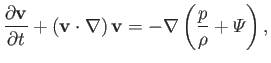

equation of motion of an inviscid incompressible fluid which, according to Equations (1.39) and (1.79), takes the

form

has the magnitude zero everywhere.

It immediately follows, from Equation (4.77), that the circulation around any arbitrary loop in an irrotational

flow pattern is zero (provided that the loop can be spanned by a surface that lies entirely within the fluid). Hence, from Kelvin's circulation theorem, if an inviscid fluid is initially irrotational

then it remains irrotational at all subsequent times. This can be seen more directly from the

equation of motion of an inviscid incompressible fluid which, according to Equations (1.39) and (1.79), takes the

form

|

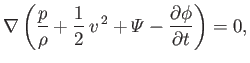

(4.82) |

because  is a constant. However, from Equation (A.171),

is a constant. However, from Equation (A.171),

Thus, we obtain

Taking the curl of this equation, and making use of the vector identities

[see Equation (A.176)],

[see Equation (A.176)],

[see Equation (A.173)], as well as the identity (A.179), and the fact that

[see Equation (A.173)], as well as the identity (A.179), and the fact that

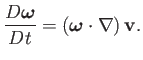

in an incompressible fluid, we obtain the vorticity evolution equation

in an incompressible fluid, we obtain the vorticity evolution equation

|

(4.85) |

Thus, if

, initially, then

, initially, then

, and, consequently,

, and, consequently,

at all subsequent times.

at all subsequent times.

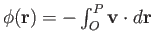

Suppose that  is a fixed point, and

is a fixed point, and  an arbitrary movable point, in an irrotational fluid. Let

an arbitrary movable point, in an irrotational fluid. Let  and

and  be joined

by two different paths,

be joined

by two different paths,  and

and  (say). It follows that

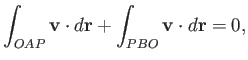

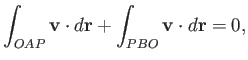

(say). It follows that  is a closed curve. Because the circulation

around such a curve in an irrotational fluid is zero, we can write

is a closed curve. Because the circulation

around such a curve in an irrotational fluid is zero, we can write

|

(4.86) |

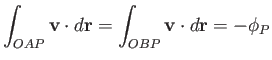

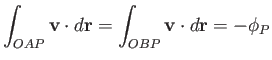

which implies that

|

(4.87) |

(say). It is clear that  is a scalar function whose value depends on the

position of

is a scalar function whose value depends on the

position of  (and the fixed point

(and the fixed point  ), but not on the path taken between

), but not on the path taken between  and

and  .

Thus, if

.

Thus, if  is the origin of our coordinate system, and

is the origin of our coordinate system, and  an arbitrary point whose position

vector is

an arbitrary point whose position

vector is  , then we have effectively defined a scalar field

, then we have effectively defined a scalar field

.

.

Consider a point  that is sufficiently close to

that is sufficiently close to  that the velocity

that the velocity  is constant along

is constant along  .

Let

.

Let

be the position vector of

be the position vector of  relative to

relative to  . It then follows that (see Section A.18)

. It then follows that (see Section A.18)

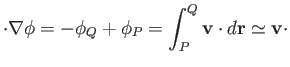

The previous equation becomes exact in the limit that

. Because

. Because  is arbitrary (provided that it is

sufficiently close to

is arbitrary (provided that it is

sufficiently close to  ), the

direction of the vector

), the

direction of the vector

is also arbitrary, which implies that

is also arbitrary, which implies that

|

(4.89) |

We, thus, conclude that if the motion of a fluid is irrotational then the associated velocity field can always be expressed as minus the

gradient of a scalar function of position,

. This scalar function is called the velocity potential, and

flow which is derived from such a potential is known as potential flow. Note that the velocity potential

is undefined to an arbitrary additive constant.

. This scalar function is called the velocity potential, and

flow which is derived from such a potential is known as potential flow. Note that the velocity potential

is undefined to an arbitrary additive constant.

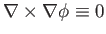

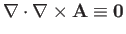

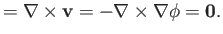

We have demonstrated that a velocity potential necessarily exists in a fluid whose velocity field is irrotational.

Conversely, when a velocity potential exists the flow is necessarily irrotational. This follows because [see Equation (A.176)]

|

(4.90) |

Incidentally, the fluid velocity at any given point in an irrotational fluid is normal to the constant- surface that

passes through that point.

surface that

passes through that point.

If a flow pattern is both irrotational and incompressible then we have

|

(4.91) |

and

|

(4.92) |

These two expressions can be combined to give (see Section A.21)

|

(4.93) |

In other words, the velocity potential in an incompressible irrotational fluid satisfies Laplace's equation.

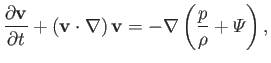

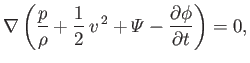

According to Equation (4.84), if the flow pattern in an incompressible inviscid fluid is also irrotational, so that

and

and

, then we can write

, then we can write

|

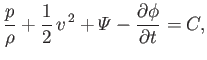

(4.94) |

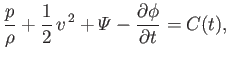

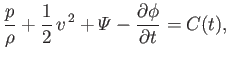

which implies that

|

(4.95) |

where  is uniform in space, but can vary in time. In fact, the time variation of

is uniform in space, but can vary in time. In fact, the time variation of  can be eliminated

by adding the appropriate function of time (but not of space) to the velocity potential,

can be eliminated

by adding the appropriate function of time (but not of space) to the velocity potential,  . Note that such

a procedure does not modify the instantaneous velocity field

. Note that such

a procedure does not modify the instantaneous velocity field  derived from

derived from  . Thus, the previous equation can

be rewritten

. Thus, the previous equation can

be rewritten

|

(4.96) |

where  is constant in both space and time. Expression (4.96) is a generalization of Bernoulli's theorem (see Section 4.3)

that takes non-steady flow into account. However, this generalization is only valid for irrotational flow. For the special

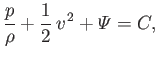

case of steady flow, we get

is constant in both space and time. Expression (4.96) is a generalization of Bernoulli's theorem (see Section 4.3)

that takes non-steady flow into account. However, this generalization is only valid for irrotational flow. For the special

case of steady flow, we get

|

(4.97) |

which demonstrates that for steady irrotational flow the constant in Bernoulli's theorem is the same on all streamlines. (See Section 4.3.)

Next: Exercises

Up: Incompressible Inviscid Flow

Previous: Kelvin Circulation Theorem

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-03-31

![]() is a fixed point, and

is a fixed point, and ![]() an arbitrary movable point, in an irrotational fluid. Let

an arbitrary movable point, in an irrotational fluid. Let ![]() and

and ![]() be joined

by two different paths,

be joined

by two different paths, ![]() and

and ![]() (say). It follows that

(say). It follows that ![]() is a closed curve. Because the circulation

around such a curve in an irrotational fluid is zero, we can write

is a closed curve. Because the circulation

around such a curve in an irrotational fluid is zero, we can write

![]() that is sufficiently close to

that is sufficiently close to ![]() that the velocity

that the velocity ![]() is constant along

is constant along ![]() .

Let

.

Let

![]() be the position vector of

be the position vector of ![]() relative to

relative to ![]() . It then follows that (see Section A.18)

. It then follows that (see Section A.18)

![]()

![]() and

and

![]() , then we can write

, then we can write