|

|

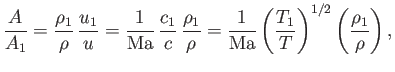

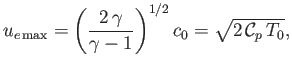

Of course, the net mass flow rate, ![]() , must be constant along the nozzle, so

, must be constant along the nozzle, so

| (14.69) |

|

(14.70) |

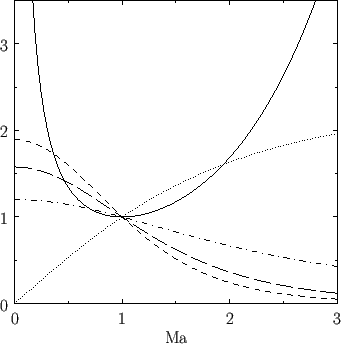

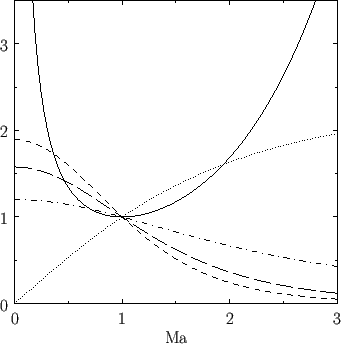

Figure 14.1 shows ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

,

![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , plotted as functions of the local

Mach number,

, plotted as functions of the local

Mach number, ![]() , for an ideal gas with

, for an ideal gas with

![]() . Here, use has been made of Equations (14.71), (14.67),

(14.68), (14.66), and (14.72), respectively. Inspecting the curves, we can see, somewhat surprisingly, that the cross-sectional area function,

. Here, use has been made of Equations (14.71), (14.67),

(14.68), (14.66), and (14.72), respectively. Inspecting the curves, we can see, somewhat surprisingly, that the cross-sectional area function, ![]() , attains

a minimum value when

, attains

a minimum value when

![]() . In fact, the figure indicates that, for subsonic flow (

. In fact, the figure indicates that, for subsonic flow (

![]() ), a decreasing cross-sectional

area of the nozzle in the direction of the gas flow leads to an increasing flow speed, and decreasing pressure, density, and temperature.

However, for supersonic flow (

), a decreasing cross-sectional

area of the nozzle in the direction of the gas flow leads to an increasing flow speed, and decreasing pressure, density, and temperature.

However, for supersonic flow (

![]() ), this behavior is reversed, and an increasing cross-sectional area of the nozzle leads to an increasing flow speed, and decreasing pressure, density, and temperature. We conclude that local Mach number of gas flowing through a converging nozzle (i.e., a nozzle whose cross-sectional area decreases monotonically

in the direction of the gas flow) can never exceed unity. Moreover, the maximum Mach number (i.e., unity) is achieved on exit from the nozzle, where the

cross-sectional area is smallest. On the other hand, the local Mach number of gas flowing through a converging-diverging

nozzle (i.e., a nozzle whose cross-sectional area initially decreases

in the direction of the gas flow, attains a minimum value, and then increases) can exceed unity. For this to happen, the

flow conditions must be arranged such that the sonic point corresponds precisely to the narrowest point of the nozzle,

which is generally known as the throat. In this case, as the gas flows through the converging part of the nozzle, the

local cross-sectional area,

), this behavior is reversed, and an increasing cross-sectional area of the nozzle leads to an increasing flow speed, and decreasing pressure, density, and temperature. We conclude that local Mach number of gas flowing through a converging nozzle (i.e., a nozzle whose cross-sectional area decreases monotonically

in the direction of the gas flow) can never exceed unity. Moreover, the maximum Mach number (i.e., unity) is achieved on exit from the nozzle, where the

cross-sectional area is smallest. On the other hand, the local Mach number of gas flowing through a converging-diverging

nozzle (i.e., a nozzle whose cross-sectional area initially decreases

in the direction of the gas flow, attains a minimum value, and then increases) can exceed unity. For this to happen, the

flow conditions must be arranged such that the sonic point corresponds precisely to the narrowest point of the nozzle,

which is generally known as the throat. In this case, as the gas flows through the converging part of the nozzle, the

local cross-sectional area, ![]() , travels down the left-hand, subsonic branch of the

, travels down the left-hand, subsonic branch of the ![]() curve shown in Figure 14.1,

while the flow speed,

curve shown in Figure 14.1,

while the flow speed, ![]() , simultaneously increases. After passing through the throat at the sonic speed, the

gas flows through the diverging part of the nozzle, and the cross-sectional area travels up the right-hand, supersonic

branch of the

, simultaneously increases. After passing through the throat at the sonic speed, the

gas flows through the diverging part of the nozzle, and the cross-sectional area travels up the right-hand, supersonic

branch of the ![]() curve, while the flow speed continues to increase. The type of converging-diverging

nozzle just described is known as a de Laval nozzle, after its inventor, Gustaf de Laval (1845-1913).

curve, while the flow speed continues to increase. The type of converging-diverging

nozzle just described is known as a de Laval nozzle, after its inventor, Gustaf de Laval (1845-1913).

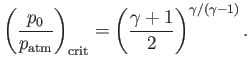

Consider a de Laval nozzle whose gas supply is derived from a large reservoir. Assuming that the gas in the reservoir is essentially

at rest, it follows that the temperature, pressure, and density of the gas in the reservoir correspond to the stagnation

temperature, pressure, and density--![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , respectively. Equation (14.63)-(14.65) then specify the

temperature, pressure, and density of the gas at the throat of the nozzle--

, respectively. Equation (14.63)-(14.65) then specify the

temperature, pressure, and density of the gas at the throat of the nozzle--![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , respectively--in terms of the

temperature, pressure, and density of the gas in the reservoir.

, respectively--in terms of the

temperature, pressure, and density of the gas in the reservoir.

Suppose that a de Laval nozzle exhausts gas into the atmosphere, whose pressure is

![]() . Now, for the case of incompressible flow,

the pressure of the gas exhausted from a nozzle,

. Now, for the case of incompressible flow,

the pressure of the gas exhausted from a nozzle, ![]() (say), must match the ambient pressure,

(say), must match the ambient pressure,

![]() . The reason for this

is that any mismatch between the exhaust and ambient pressures is instantly communicated to the whole fluid by means of sound waves that travel infinitely fast

(because an incompressible fluid corresponds to the limit

. The reason for this

is that any mismatch between the exhaust and ambient pressures is instantly communicated to the whole fluid by means of sound waves that travel infinitely fast

(because an incompressible fluid corresponds to the limit

![]() ). Of course, the sound speed is finite in a

compressible gas.

However, in subsonic compressible flow, upstream communication

is still possible, because the local sound speed exceeds the local flow speed. However, in supersonic compressible flow,

upstream communication is impossible, because sound waves cannot catch up with the flow. Consequently, in the case of a nozzle

with a subsonic exhaust speed, we would generally expect the exhaust pressure to match the ambient pressure. However,

in the case of a nozzle with a supersonic exhaust speed, the exhaust pressure can be significantly different to the ambient pressure.

). Of course, the sound speed is finite in a

compressible gas.

However, in subsonic compressible flow, upstream communication

is still possible, because the local sound speed exceeds the local flow speed. However, in supersonic compressible flow,

upstream communication is impossible, because sound waves cannot catch up with the flow. Consequently, in the case of a nozzle

with a subsonic exhaust speed, we would generally expect the exhaust pressure to match the ambient pressure. However,

in the case of a nozzle with a supersonic exhaust speed, the exhaust pressure can be significantly different to the ambient pressure.

Equation (14.61) yields

![$\displaystyle {\rm Ma}_{\,e} =\sqrt{ \left(\frac{2}{\gamma-1}\right) \left[\left(\frac{p_0}{p_{\rm atm}}\right)^{(\gamma-1)/\gamma}-1\right]}.$](img5425.png) |

(14.74) |

|

(14.75) |

Equations (14.64) and (14.67) yield

![$\displaystyle u_e=\sqrt{{\cal R}\,T_0\left(\frac{2\,\gamma}{\gamma-1}\right)\left[1-\left(\frac{p_e}{p_0}\right) ^{(\gamma-1)/\gamma}\right]}.$](img5432.png) |

(14.78) |

|

(14.79) |

If the exhaust pressure of a de Laval nozzle is higher than the ambient pressure,

![]() , then the gas is

said to be under-expanded. In this case, a pattern of standing shock waves, called shock diamonds,

forms in the exhaust plume external to the nozzle. On the other hand, if the exhaust pressure is lower than the ambient pressure,

, then the gas is

said to be under-expanded. In this case, a pattern of standing shock waves, called shock diamonds,

forms in the exhaust plume external to the nozzle. On the other hand, if the exhaust pressure is lower than the ambient pressure,

![]() , then the gas is said to be over-expanded. In this case, a static shock front forms inside the

diverging part of the nozzle. (See Section 14.8.) As the gas passes through the front, its speed drops abruptly from a supersonic to a subsonic value,

whereas the pressure, density, and temperature all increase abruptly.

As the subsonic gas flows through the remainder of the nozzle, its velocity decreases further.

, then the gas is said to be over-expanded. In this case, a static shock front forms inside the

diverging part of the nozzle. (See Section 14.8.) As the gas passes through the front, its speed drops abruptly from a supersonic to a subsonic value,

whereas the pressure, density, and temperature all increase abruptly.

As the subsonic gas flows through the remainder of the nozzle, its velocity decreases further.