Next: Von Kármán Momentum Integral

Up: Incompressible Boundary Layers

Previous: Boundary Layer on a

Wake Downstream of a Flat Plate

As we saw in the previous section, if a flat plate of negligible thickness, and finite length, is placed in the path of a uniform high Reynolds number

flow, directed parallel to the plate, then thin boundary layers form above and below the plate. Outside the

layers, the flow is irrotational, and essentially inviscid. Inside the layers, the flow is modified by viscosity,

and has non-zero vorticity. Downstream of the plate, the boundary layers are convected by the flow, and merge to form a thin wake. (See

Figure 8.4.)

Within the wake, the flow is modified by viscosity, and possesses finite vorticity. Outside the wake, the downstream flow

remains irrotational, and effectively inviscid.

Because there is no solid surface embedded in the wake, acting to retard the flow, we would

expect the action of viscosity to cause the velocity within the wake, a long distance downstream of the plate, to closely match that of

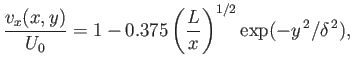

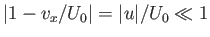

the unperturbed flow. In other words, we expect the fluid velocity within the wake to take the form

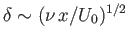

where

|

(8.85) |

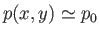

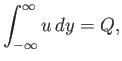

Assuming that, within the wake,

where

is the wake thickness, fluid continuity requires that

is the wake thickness, fluid continuity requires that

|

(8.88) |

The flow external to the boundary layers, and the wake, is both uniform and essentially inviscid. Hence, according to Bernoulli's theorem, the pressure in this region is also uniform. [See Equation (8.22).] However, as we saw in Section 8.3, there is no  -variation of the pressure across the boundary layers.

It follows that the pressure is uniform within the layers.

Thus, it is reasonable to assume that the pressure is also uniform within the wake, because the wake is formed via

the convection of the boundary layers downstream of the plate. We conclude

that

-variation of the pressure across the boundary layers.

It follows that the pressure is uniform within the layers.

Thus, it is reasonable to assume that the pressure is also uniform within the wake, because the wake is formed via

the convection of the boundary layers downstream of the plate. We conclude

that

|

(8.89) |

everywhere in the fluid, where  is a constant.

is a constant.

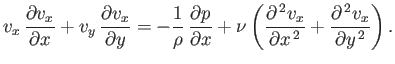

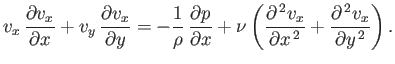

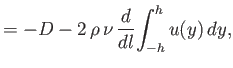

The  -component of the fluid equation of motion is written

-component of the fluid equation of motion is written

|

(8.90) |

Making use of Equations (8.83)-(8.89), the previous expression reduces to

|

(8.91) |

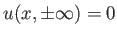

The boundary condition

|

(8.92) |

ensures that the flow outside the wake remains unperturbed.

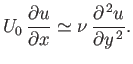

Note that Equation (8.91) has the same mathematical form as a conventional diffusion equation, with  playing the role of time, and

playing the role of time, and

playing the role of the diffusion coefficient. Hence, by analogy with the standard solution

of the diffusion equation, we would expect

playing the role of the diffusion coefficient. Hence, by analogy with the standard solution

of the diffusion equation, we would expect

(Riley 1974).

(Riley 1974).

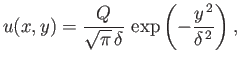

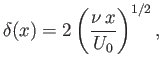

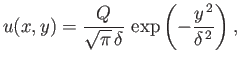

As can easily be demonstrated, the self-similar solution to Equation (8.91), subject to the boundary condition (8.92),

is

|

(8.93) |

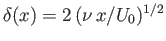

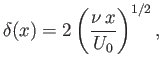

where

|

(8.94) |

and  is a constant.

It follows that

is a constant.

It follows that

|

(8.95) |

because, as is well-known,

(Riley 1974). As expected, the width of the wake scales as

(Riley 1974). As expected, the width of the wake scales as  .

.

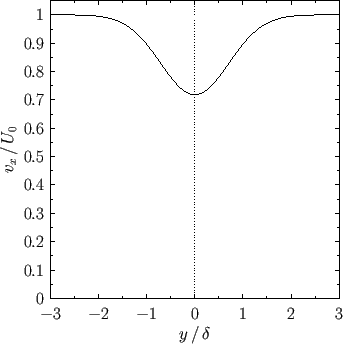

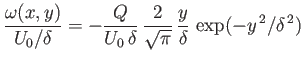

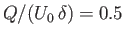

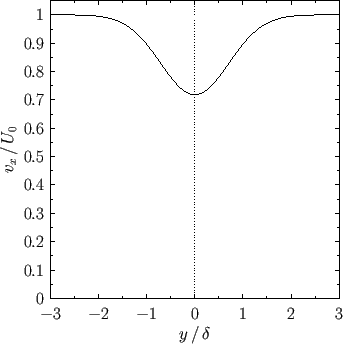

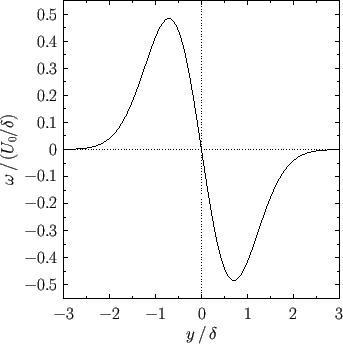

Figure:

Tangential velocity profile across the wake of a flat plate of negligible

thickness located at  . The profile is calculated for

. The profile is calculated for

.

.

|

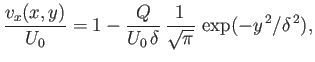

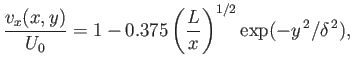

The tangential velocity profile across the wake, which takes the form

|

(8.96) |

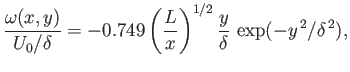

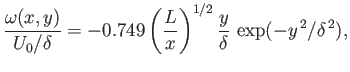

is plotted in Figure 8.8. In addition, the vorticity profile across the wake, which is

written

|

(8.97) |

is shown in Figure 8.9. It can be seen that the profiles pictured in Figures 8.8 and 8.9 are essentially smoothed out versions of the boundary

layer profiles shown in Figures 8.5 and 8.6, respectively.

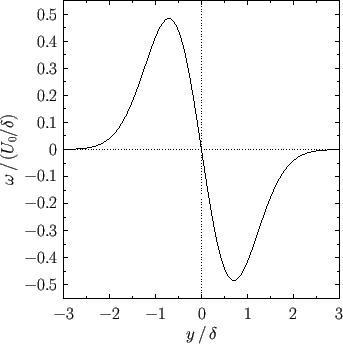

Figure:

Vorticity profile across the boundary layers above and below a flat plate of negligible

thickness located at  . The profile is calculated for

. The profile is calculated for

.

.

|

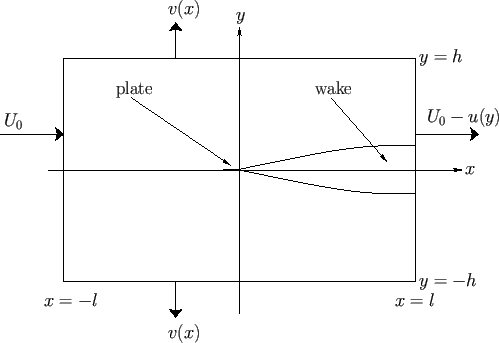

Suppose that the plate and a portion of its trailing wake are enclosed by a cuboid control volume of unit depth (in the  -direction)

that extends from

-direction)

that extends from  to

to  and from

and from  to

to  . (See Figure 8.10.) Here,

. (See Figure 8.10.) Here,  and

and

, where

, where  is the

length of the plate, and

is the

length of the plate, and  the width of the wake. Hence, the control volume extends well upstream and

downstream of the plate. Moreover, the volume is much wider than the wake.

the width of the wake. Hence, the control volume extends well upstream and

downstream of the plate. Moreover, the volume is much wider than the wake.

Figure 8.10:

Control volume surrounding a flat plate and its trailing wake.

|

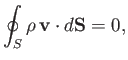

Let us apply the integral form of the fluid equation of continuity to the control volume. For a

steady state, this reduces to (see Section 1.9)

|

(8.98) |

where  is the bounding surface of the control volume.

The normal fluid velocity is

is the bounding surface of the control volume.

The normal fluid velocity is  at

at  ,

,

at

at  , and

, and  at

at  , as indicated in the figure.

Hence, Equation (8.98) yields

, as indicated in the figure.

Hence, Equation (8.98) yields

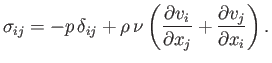

![$\displaystyle -\int_{-h}^h\rho\,U_0\,dy + \int_{-h}^{h}\rho\,[U_0-u(y)]\,dy+2\int_{-l}^{l}\rho\,v(x)\,dx = 0,$](img3046.png) |

(8.99) |

or

|

(8.100) |

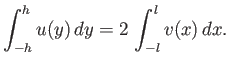

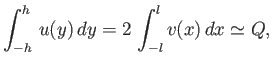

However, given that

for

for

, and because

, and because

, it is a good approximation to replace the limits of integration on the left-hand side of the

previous expression by

, it is a good approximation to replace the limits of integration on the left-hand side of the

previous expression by

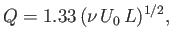

. Thus, from Equation (8.95),

. Thus, from Equation (8.95),

|

(8.101) |

where  is independent of

is independent of  .

Note that the slight retardation of the flow inside the wake, due to the presence of the plate, which is parameterized by

.

Note that the slight retardation of the flow inside the wake, due to the presence of the plate, which is parameterized by  ,

necessitates a small lateral outflow,

,

necessitates a small lateral outflow,  , in the region of the fluid external to the wake.

, in the region of the fluid external to the wake.

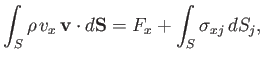

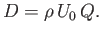

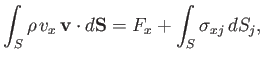

Let us now apply the integral form of the  -component of the fluid equation of motion to the control volume. For a steady state,

this reduces to (see Section 1.11)

-component of the fluid equation of motion to the control volume. For a steady state,

this reduces to (see Section 1.11)

|

(8.102) |

where  is the net

is the net  -directed force exerted on the fluid within the control volume by the plate. It follows,

from Newton's third law of motion, that

-directed force exerted on the fluid within the control volume by the plate. It follows,

from Newton's third law of motion, that

, where

, where  is the viscous drag force per unit width (in the

is the viscous drag force per unit width (in the  -direction) acting on the plate in the

-direction) acting on the plate in the  -direction.

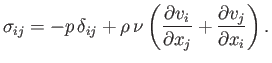

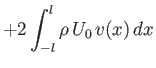

In an incompressible fluid (see Section 1.6),

-direction.

In an incompressible fluid (see Section 1.6),

|

(8.103) |

Hence, we obtain

because the pressure within the fluid is essentially uniform, the tangential fluid velocity at  is

is  ,

and

,

and  is assumed to be negligible at

is assumed to be negligible at  . Making use of Equation (8.101), as

well as the fact that

. Making use of Equation (8.101), as

well as the fact that  is independent of

is independent of  , we get

, we get

|

(8.105) |

Here, we have neglected any terms that are second order in the small quantity  .

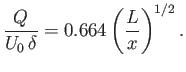

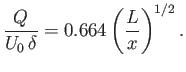

A comparison with Equation (8.79) reveals that

.

A comparison with Equation (8.79) reveals that

|

(8.106) |

or

|

(8.107) |

Hence, from Equations (8.96) and (8.97), the velocity and vorticity profiles across the layer are

|

(8.108) |

and

|

(8.109) |

respectively, where

. Finally, because the previous analysis is premised on the assumption that

. Finally, because the previous analysis is premised on the assumption that

,

it is clear that the previous three expressions are only valid when

,

it is clear that the previous three expressions are only valid when  (i.e., well downstream of the plate).

(i.e., well downstream of the plate).

The previous analysis only holds when the flow within the wake is non-turbulent. Let us assume, by analogy with the

discussion in the previous section, that

this is the case as long as the Reynolds number of the wake,

, remains less than some

critical value that is approximately

, remains less than some

critical value that is approximately  .

Because the Reynolds number of the wake can be written

.

Because the Reynolds number of the wake can be written

,

where

,

where

is the Reynolds number of the external flow, we deduce that the wake becomes turbulent

when

is the Reynolds number of the external flow, we deduce that the wake becomes turbulent

when

. Hence, the wake is always turbulent sufficiently far downstream of the plate.

Our analysis, which effectively assumes that the wake is non-turbulent in some region, immediately downstream of the plate, whose extent (in

. Hence, the wake is always turbulent sufficiently far downstream of the plate.

Our analysis, which effectively assumes that the wake is non-turbulent in some region, immediately downstream of the plate, whose extent (in  ) is large compared

with

) is large compared

with  , is thus only valid when

, is thus only valid when

.

.

Next: Von Kármán Momentum Integral

Up: Incompressible Boundary Layers

Previous: Boundary Layer on a

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-03-31

![]() -component of the fluid equation of motion is written

-component of the fluid equation of motion is written

![]() -direction)

that extends from

-direction)

that extends from ![]() to

to ![]() and from

and from ![]() to

to ![]() . (See Figure 8.10.) Here,

. (See Figure 8.10.) Here, ![]() and

and

![]() , where

, where ![]() is the

length of the plate, and

is the

length of the plate, and ![]() the width of the wake. Hence, the control volume extends well upstream and

downstream of the plate. Moreover, the volume is much wider than the wake.

the width of the wake. Hence, the control volume extends well upstream and

downstream of the plate. Moreover, the volume is much wider than the wake.

![$\displaystyle -\int_{-h}^h\rho\,U_0\,dy + \int_{-h}^{h}\rho\,[U_0-u(y)]\,dy+2\int_{-l}^{l}\rho\,v(x)\,dx = 0,$](img3046.png)

![]() -component of the fluid equation of motion to the control volume. For a steady state,

this reduces to (see Section 1.11)

-component of the fluid equation of motion to the control volume. For a steady state,

this reduces to (see Section 1.11)

![$\displaystyle -\int_{-h}^h\rho\,U_0^{\,2}\,dy+\int_{-h}^h\rho\left[U_0-u(y)\right]^{\,2}\,dy$](img3057.png)

![]() , remains less than some

critical value that is approximately

, remains less than some

critical value that is approximately ![]() .

Because the Reynolds number of the wake can be written

.

Because the Reynolds number of the wake can be written

![]() ,

where

,

where

![]() is the Reynolds number of the external flow, we deduce that the wake becomes turbulent

when

is the Reynolds number of the external flow, we deduce that the wake becomes turbulent

when

![]() . Hence, the wake is always turbulent sufficiently far downstream of the plate.

Our analysis, which effectively assumes that the wake is non-turbulent in some region, immediately downstream of the plate, whose extent (in

. Hence, the wake is always turbulent sufficiently far downstream of the plate.

Our analysis, which effectively assumes that the wake is non-turbulent in some region, immediately downstream of the plate, whose extent (in ![]() ) is large compared

with

) is large compared

with ![]() , is thus only valid when

, is thus only valid when

![]() .

.