Electromagnetic Waves

Consider a plane electromagnetic wave propagating through a vacuum in the  -direction.

Incidentally, electromagnetic waves are the only

commonly-occurring waves that do not require a medium through which to

propagate.

Suppose that the wave is linearly polarized in the

-direction.

Incidentally, electromagnetic waves are the only

commonly-occurring waves that do not require a medium through which to

propagate.

Suppose that the wave is linearly polarized in the  -direction; that is, its electric

component oscillates in the

-direction; that is, its electric

component oscillates in the  -direction. It follows that the magnetic

component of the wave oscillates in the

-direction. It follows that the magnetic

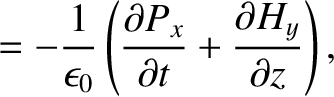

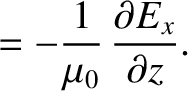

component of the wave oscillates in the  -direction (Fitzpatrick 2008). According to standard electromagnetic theory (see Appendix C), the wave is

described by the following pair of coupled partial differential equations:

where

-direction (Fitzpatrick 2008). According to standard electromagnetic theory (see Appendix C), the wave is

described by the following pair of coupled partial differential equations:

where  is the electric field-strength, and

is the electric field-strength, and  is the

magnetic intensity (i.e., the magnetic field-strength divided by

is the

magnetic intensity (i.e., the magnetic field-strength divided by

). Observe that Equations (6.116) and (6.117), which govern

the propagation of electromagnetic waves through a vacuum, are analogous

to Equations (6.53) and (6.54), which govern the propagation of

electromagnetic signals down a transmission line. In particular,

). Observe that Equations (6.116) and (6.117), which govern

the propagation of electromagnetic waves through a vacuum, are analogous

to Equations (6.53) and (6.54), which govern the propagation of

electromagnetic signals down a transmission line. In particular,  has units of

voltage over length,

has units of

voltage over length,  has units of current over length,

has units of current over length,

has

units of capacitance per unit length, and

has

units of capacitance per unit length, and  has units of

inductance per unit length.

has units of

inductance per unit length.

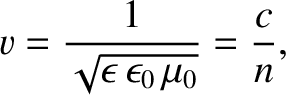

Equations (6.116) and (6.117) can be combined to give

It follows that the electric and the magnetic components of an electromagnetic wave

propagating through a vacuum both separately satisfy

a wave equation of the form (6.1). Furthermore, the phase velocity of the

wave is the velocity of light in vacuum,

|

(6.120) |

Let us search for a traveling wave solution of Equations (6.116) and (6.117), propagating in the

positive  -direction, whose electric component has the form

-direction, whose electric component has the form

|

(6.121) |

This is a valid solution provided that

|

(6.122) |

According to

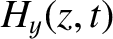

Equation (6.117), the magnetic component of the wave is written

|

(6.123) |

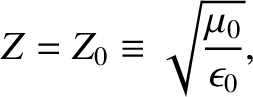

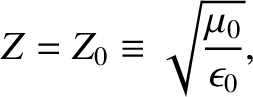

where

|

(6.124) |

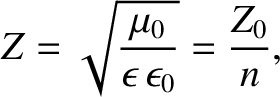

and  is the impedance of free space. [See Equation (6.74).]

Thus, the electric and magnetic components of an electromagnetic wave propagating through a vacuum are mutually perpendicular,

and also perpendicular to the direction of propagation. Moreover, the two components

oscillate in phase (i.e., they have simultaneous maxima and zeros), and

the amplitude of the magnetic component is that of the electric component

divided by the impedance of free space.

is the impedance of free space. [See Equation (6.74).]

Thus, the electric and magnetic components of an electromagnetic wave propagating through a vacuum are mutually perpendicular,

and also perpendicular to the direction of propagation. Moreover, the two components

oscillate in phase (i.e., they have simultaneous maxima and zeros), and

the amplitude of the magnetic component is that of the electric component

divided by the impedance of free space.

Multiplying Equation (6.116) by

, Equation (6.117)

by

, Equation (6.117)

by

, and adding the two resulting expressions, we obtain the

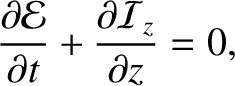

energy conservation equation

, and adding the two resulting expressions, we obtain the

energy conservation equation

|

(6.125) |

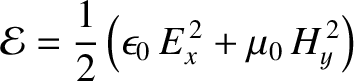

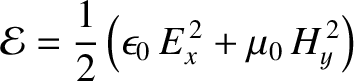

where

|

(6.126) |

is the energy density (i.e., energy per unit volume) of the wave (Fitzpatrick 2008), whereas

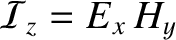

|

(6.127) |

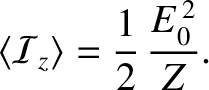

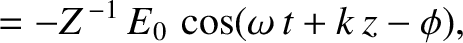

is the energy flux (i.e., power per unit area) in the positive  -direction. (See Appendix C.) The mean energy flux associated with the

-direction. (See Appendix C.) The mean energy flux associated with the  -directed electromagnetic wave specified

in Equations (6.121) and (6.123) is thus

-directed electromagnetic wave specified

in Equations (6.121) and (6.123) is thus

|

(6.128) |

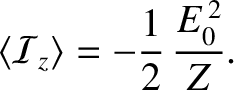

For a similar wave propagating in the negative  -direction, it can be

demonstrated that

and

-direction, it can be

demonstrated that

and

|

(6.131) |

Consider a plane electromagnetic wave, linearly polarized in the  -direction, that

propagates in the

-direction, that

propagates in the  -direction through a transparent dielectric medium, such as glass or water. As is well-known (Fitzpatrick 2008), the electric component of the wave causes the neutral molecules making

up the medium to polarize; that is, it causes a small separation to develop between the mean positions of the positively

and negatively charged constituents of the molecules (i.e., the atomic nuclei and the

orbiting electrons). [Incidentally, it can be

shown that the magnetic component of the wave has a negligible influence on the

molecules, provided the wave amplitude is sufficiently small that the wave electric

field does not cause the electrons and nuclei to move with relativistic velocities (ibid.).] If the mean position of the positively charged

constituents of a given molecule, of net charge

-direction through a transparent dielectric medium, such as glass or water. As is well-known (Fitzpatrick 2008), the electric component of the wave causes the neutral molecules making

up the medium to polarize; that is, it causes a small separation to develop between the mean positions of the positively

and negatively charged constituents of the molecules (i.e., the atomic nuclei and the

orbiting electrons). [Incidentally, it can be

shown that the magnetic component of the wave has a negligible influence on the

molecules, provided the wave amplitude is sufficiently small that the wave electric

field does not cause the electrons and nuclei to move with relativistic velocities (ibid.).] If the mean position of the positively charged

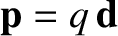

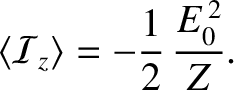

constituents of a given molecule, of net charge  , develops a vector displacement

, develops a vector displacement

with respect to the mean position of the negatively charged constituents, of net charge

with respect to the mean position of the negatively charged constituents, of net charge  , in response to a wave electric field

, in response to a wave electric field  , then the

associated electric dipole moment is

, then the

associated electric dipole moment is

, where

, where

is generally parallel to

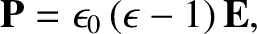

is generally parallel to  (ibid.). Furthermore, if there are

(ibid.). Furthermore, if there are  such molecules per unit volume then the electric dipole moment per unit volume

is written

such molecules per unit volume then the electric dipole moment per unit volume

is written

. In a linear, isotropic, dielectric medium (ibid.),

. In a linear, isotropic, dielectric medium (ibid.),

|

(6.132) |

where

is a dimensionless quantity, known as the relative dielectric

constant, that is a property of the medium in question. In the presence of

a dielectric medium, Equations (6.116) and (6.117) generalize to give

(See Appendix C.)

When combined with Equation (6.132), these expressions yield

It can be seen that the previous equations are just like the corresponding vacuum equations,

(6.116) and (6.117), except that

is a dimensionless quantity, known as the relative dielectric

constant, that is a property of the medium in question. In the presence of

a dielectric medium, Equations (6.116) and (6.117) generalize to give

(See Appendix C.)

When combined with Equation (6.132), these expressions yield

It can be seen that the previous equations are just like the corresponding vacuum equations,

(6.116) and (6.117), except that

has been replaced by

has been replaced by

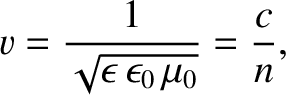

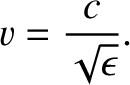

. It immediately follows that the phase velocity of an

electromagnetic wave propagating through a dielectric medium is

. It immediately follows that the phase velocity of an

electromagnetic wave propagating through a dielectric medium is

|

(6.137) |

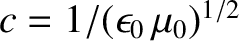

where

is the velocity of light in vacuum, and

the dimensionless quantity

is the velocity of light in vacuum, and

the dimensionless quantity

|

(6.138) |

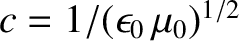

is known as the refractive index of the medium. Thus, an electromagnetic

wave propagating through a transparent dielectric medium does so at a

phase velocity that is less than the velocity of light in vacuum by a

factor  (where

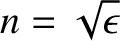

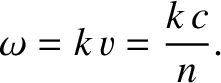

(where  ). The dispersion relation of the wave is thus

). The dispersion relation of the wave is thus

|

(6.139) |

Furthermore, the impedance of a transparent dielectric medium becomes

|

(6.140) |

where  is the impedance of free space.

is the impedance of free space.

Incidentally, the signal that travels down a transmission line is a form of guided electromagnetic wave. It follows

that if the space between the two conductors that constitute the line is filled with dielectric material of

relative dielectric constant  then the signal propagates down the line at the

reduced phase velocity

then the signal propagates down the line at the

reduced phase velocity

|

(6.141) |

This occurs because the dielectric material

increases the capacitance per unit length of the line by a factor  , but leaves the

inductance per unit length unchanged. (See Section 6.6.) For the same reason, the presence of the dielectric

material decreases the impedance of the line by a factor

, but leaves the

inductance per unit length unchanged. (See Section 6.6.) For the same reason, the presence of the dielectric

material decreases the impedance of the line by a factor

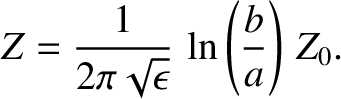

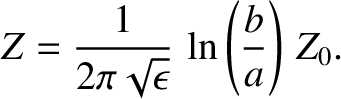

. Hence, the impedance of a

dielectric filled co-axial cable is [cf., Equation (6.78)]

. Hence, the impedance of a

dielectric filled co-axial cable is [cf., Equation (6.78)]

|

(6.142) |

Here,  and

and  are the radii of the inner and outer conductors, respectively.

are the radii of the inner and outer conductors, respectively.

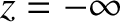

Suppose that the plane  forms the interface between two transparent dielectric

media of refractive indices

forms the interface between two transparent dielectric

media of refractive indices  and

and  . Let the first medium occupy the

region

. Let the first medium occupy the

region  , and the second the region

, and the second the region  . Suppose that a plane electromagnetic

wave, linearly polarized in the

. Suppose that a plane electromagnetic

wave, linearly polarized in the  -direction, and propagating in the positive

-direction, and propagating in the positive  -direction, is launched toward the interface

from a wave source of angular frequency

-direction, is launched toward the interface

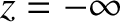

from a wave source of angular frequency  situated at

situated at  . We expect the

wave incident on the interface to be partly reflected, and partly transmitted.

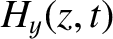

The wave electric and magnetic fields in the region

. We expect the

wave incident on the interface to be partly reflected, and partly transmitted.

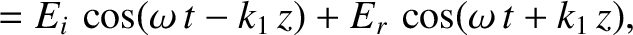

The wave electric and magnetic fields in the region  are written

are written

where  is the amplitude of (the electric component of) the incident wave,

is the amplitude of (the electric component of) the incident wave,  the amplitude of the reflected wave,

the amplitude of the reflected wave,

, and

, and

.

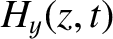

The wave electric and magnetic fields in the region

.

The wave electric and magnetic fields in the region  take the form

where

take the form

where  is the amplitude of the transmitted wave,

is the amplitude of the transmitted wave,

, and

, and

.

According to standard electromagnetic theory (see Appendix C), the appropriate matching conditions at the

interface (

.

According to standard electromagnetic theory (see Appendix C), the appropriate matching conditions at the

interface ( ) are that

) are that  and

and  are both continuous. Thus,

continuity of

are both continuous. Thus,

continuity of  yields

yields

|

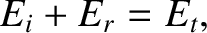

(6.147) |

whereas continuity of  gives

gives

|

(6.148) |

because

.

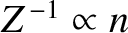

It follows that

The coefficient of reflection,

.

It follows that

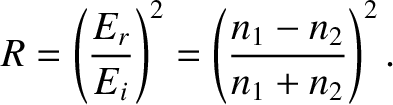

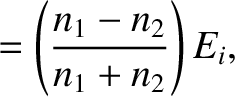

The coefficient of reflection,  , is defined as the ratio of the reflected to the incident energy

flux, so that

, is defined as the ratio of the reflected to the incident energy

flux, so that

|

(6.151) |

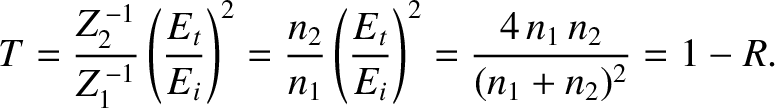

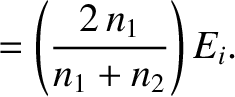

Likewise, the coefficient of transmission,  , is the ratio of the

transmitted to the incident energy flux, so that

, is the ratio of the

transmitted to the incident energy flux, so that

|

(6.152) |

It can be seen, first of all, that if  then

then  and

and  .

In other words, if the two media have the same indices of refraction then

there is no reflection at the interface between them, and the transmitted

wave is consequently equal in amplitude to the incident wave. On the other

hand, if

.

In other words, if the two media have the same indices of refraction then

there is no reflection at the interface between them, and the transmitted

wave is consequently equal in amplitude to the incident wave. On the other

hand, if

then there is always some reflection at the interface. Indeed,

the amplitude of the reflected wave is roughly proportional to the difference between

then there is always some reflection at the interface. Indeed,

the amplitude of the reflected wave is roughly proportional to the difference between  and

and  . This has important practical consequences.

We can only see a clean pane of glass in a window because some of the light incident

on an air/glass interface is reflected, as a consequence of the different refractive indices

of air and glass. As is well-known, it is a lot more difficult to see glass when it is submerged in water. This is because the refractive indices of glass and water are quite similar, and so there is very little reflection of light

incident on a water/glass interface.

. This has important practical consequences.

We can only see a clean pane of glass in a window because some of the light incident

on an air/glass interface is reflected, as a consequence of the different refractive indices

of air and glass. As is well-known, it is a lot more difficult to see glass when it is submerged in water. This is because the refractive indices of glass and water are quite similar, and so there is very little reflection of light

incident on a water/glass interface.

According to Equation (6.149),  when

when  .

The negative sign indicates a

.

The negative sign indicates a  radian phase shift of the (electric component of the) reflected wave, with

respect to the incident wave. We conclude that there is a

radian phase shift of the (electric component of the) reflected wave, with

respect to the incident wave. We conclude that there is a  radian phase shift of the reflected wave, relative to the incident wave, on reflection from an

interface with a

medium of greater refractive index. Conversely, there is zero

phase shift

on reflection from an interface with a medium of lesser refractive index. (This effect is important in thin-film interference. See Section 10.5.)

radian phase shift of the reflected wave, relative to the incident wave, on reflection from an

interface with a

medium of greater refractive index. Conversely, there is zero

phase shift

on reflection from an interface with a medium of lesser refractive index. (This effect is important in thin-film interference. See Section 10.5.)

Equations (6.149)–(6.152) are analogous to Equations (6.87)–(6.90), with the inverse of the refractive index playing the role of

impedance. This suggests, by analogy with earlier analysis, that we

can prevent reflection of an electromagnetic wave normally incident at an interface between two

transparent dielectric media of different refractive indices by separating the media in question

by a thin transparent layer whose thickness is one quarter of a wavelength, and whose

refractive index is the geometric mean of the refractive indices of the two

media. This is the physical principle behind the non-reflective lens coatings used

in high-quality optical instruments. (See Exercise 15.)

-direction.

Incidentally, electromagnetic waves are the only

commonly-occurring waves that do not require a medium through which to

propagate.

Suppose that the wave is linearly polarized in the

-direction.

Incidentally, electromagnetic waves are the only

commonly-occurring waves that do not require a medium through which to

propagate.

Suppose that the wave is linearly polarized in the  -direction; that is, its electric

component oscillates in the

-direction; that is, its electric

component oscillates in the  -direction. It follows that the magnetic

component of the wave oscillates in the

-direction. It follows that the magnetic

component of the wave oscillates in the  -direction (Fitzpatrick 2008). According to standard electromagnetic theory (see Appendix C), the wave is

described by the following pair of coupled partial differential equations:

where

-direction (Fitzpatrick 2008). According to standard electromagnetic theory (see Appendix C), the wave is

described by the following pair of coupled partial differential equations:

where  is the electric field-strength, and

is the electric field-strength, and  is the

magnetic intensity (i.e., the magnetic field-strength divided by

is the

magnetic intensity (i.e., the magnetic field-strength divided by

). Observe that Equations (6.116) and (6.117), which govern

the propagation of electromagnetic waves through a vacuum, are analogous

to Equations (6.53) and (6.54), which govern the propagation of

electromagnetic signals down a transmission line. In particular,

). Observe that Equations (6.116) and (6.117), which govern

the propagation of electromagnetic waves through a vacuum, are analogous

to Equations (6.53) and (6.54), which govern the propagation of

electromagnetic signals down a transmission line. In particular,  has units of

voltage over length,

has units of

voltage over length,  has units of current over length,

has units of current over length,

has

units of capacitance per unit length, and

has

units of capacitance per unit length, and  has units of

inductance per unit length.

has units of

inductance per unit length.

-direction, whose electric component has the form

-direction, whose electric component has the form

is the impedance of free space. [See Equation (6.74).]

Thus, the electric and magnetic components of an electromagnetic wave propagating through a vacuum are mutually perpendicular,

and also perpendicular to the direction of propagation. Moreover, the two components

oscillate in phase (i.e., they have simultaneous maxima and zeros), and

the amplitude of the magnetic component is that of the electric component

divided by the impedance of free space.

is the impedance of free space. [See Equation (6.74).]

Thus, the electric and magnetic components of an electromagnetic wave propagating through a vacuum are mutually perpendicular,

and also perpendicular to the direction of propagation. Moreover, the two components

oscillate in phase (i.e., they have simultaneous maxima and zeros), and

the amplitude of the magnetic component is that of the electric component

divided by the impedance of free space.

, Equation (6.117)

by

, Equation (6.117)

by

, and adding the two resulting expressions, we obtain the

energy conservation equation

, and adding the two resulting expressions, we obtain the

energy conservation equation

-direction. (See Appendix C.) The mean energy flux associated with the

-direction. (See Appendix C.) The mean energy flux associated with the  -directed electromagnetic wave specified

in Equations (6.121) and (6.123) is thus

For a similar wave propagating in the negative

-directed electromagnetic wave specified

in Equations (6.121) and (6.123) is thus

For a similar wave propagating in the negative  -direction, it can be

demonstrated that

-direction, it can be

demonstrated that

-direction, that

propagates in the

-direction, that

propagates in the  -direction through a transparent dielectric medium, such as glass or water. As is well-known (Fitzpatrick 2008), the electric component of the wave causes the neutral molecules making

up the medium to polarize; that is, it causes a small separation to develop between the mean positions of the positively

and negatively charged constituents of the molecules (i.e., the atomic nuclei and the

orbiting electrons). [Incidentally, it can be

shown that the magnetic component of the wave has a negligible influence on the

molecules, provided the wave amplitude is sufficiently small that the wave electric

field does not cause the electrons and nuclei to move with relativistic velocities (ibid.).] If the mean position of the positively charged

constituents of a given molecule, of net charge

-direction through a transparent dielectric medium, such as glass or water. As is well-known (Fitzpatrick 2008), the electric component of the wave causes the neutral molecules making

up the medium to polarize; that is, it causes a small separation to develop between the mean positions of the positively

and negatively charged constituents of the molecules (i.e., the atomic nuclei and the

orbiting electrons). [Incidentally, it can be

shown that the magnetic component of the wave has a negligible influence on the

molecules, provided the wave amplitude is sufficiently small that the wave electric

field does not cause the electrons and nuclei to move with relativistic velocities (ibid.).] If the mean position of the positively charged

constituents of a given molecule, of net charge  , develops a vector displacement

, develops a vector displacement

with respect to the mean position of the negatively charged constituents, of net charge

with respect to the mean position of the negatively charged constituents, of net charge  , in response to a wave electric field

, in response to a wave electric field  , then the

associated electric dipole moment is

, then the

associated electric dipole moment is

, where

, where

is generally parallel to

is generally parallel to  (ibid.). Furthermore, if there are

(ibid.). Furthermore, if there are  such molecules per unit volume then the electric dipole moment per unit volume

is written

such molecules per unit volume then the electric dipole moment per unit volume

is written

. In a linear, isotropic, dielectric medium (ibid.),

. In a linear, isotropic, dielectric medium (ibid.),

is a dimensionless quantity, known as the relative dielectric

constant, that is a property of the medium in question. In the presence of

a dielectric medium, Equations (6.116) and (6.117) generalize to give

is a dimensionless quantity, known as the relative dielectric

constant, that is a property of the medium in question. In the presence of

a dielectric medium, Equations (6.116) and (6.117) generalize to give

has been replaced by

has been replaced by

. It immediately follows that the phase velocity of an

electromagnetic wave propagating through a dielectric medium is

. It immediately follows that the phase velocity of an

electromagnetic wave propagating through a dielectric medium is

is the velocity of light in vacuum, and

the dimensionless quantity

is the velocity of light in vacuum, and

the dimensionless quantity

(where

(where  ). The dispersion relation of the wave is thus

). The dispersion relation of the wave is thus

is the impedance of free space.

is the impedance of free space.

then the signal propagates down the line at the

reduced phase velocity

then the signal propagates down the line at the

reduced phase velocity

, but leaves the

inductance per unit length unchanged. (See Section 6.6.) For the same reason, the presence of the dielectric

material decreases the impedance of the line by a factor

, but leaves the

inductance per unit length unchanged. (See Section 6.6.) For the same reason, the presence of the dielectric

material decreases the impedance of the line by a factor

. Hence, the impedance of a

dielectric filled co-axial cable is [cf., Equation (6.78)]

. Hence, the impedance of a

dielectric filled co-axial cable is [cf., Equation (6.78)]

and

and  are the radii of the inner and outer conductors, respectively.

are the radii of the inner and outer conductors, respectively.

forms the interface between two transparent dielectric

media of refractive indices

forms the interface between two transparent dielectric

media of refractive indices  and

and  . Let the first medium occupy the

region

. Let the first medium occupy the

region  , and the second the region

, and the second the region  . Suppose that a plane electromagnetic

wave, linearly polarized in the

. Suppose that a plane electromagnetic

wave, linearly polarized in the  -direction, and propagating in the positive

-direction, and propagating in the positive  -direction, is launched toward the interface

from a wave source of angular frequency

-direction, is launched toward the interface

from a wave source of angular frequency  situated at

situated at  . We expect the

wave incident on the interface to be partly reflected, and partly transmitted.

The wave electric and magnetic fields in the region

. We expect the

wave incident on the interface to be partly reflected, and partly transmitted.

The wave electric and magnetic fields in the region  are written

are written

is the amplitude of (the electric component of) the incident wave,

is the amplitude of (the electric component of) the incident wave,  the amplitude of the reflected wave,

the amplitude of the reflected wave,

, and

, and

.

The wave electric and magnetic fields in the region

.

The wave electric and magnetic fields in the region  take the form

take the form

is the amplitude of the transmitted wave,

is the amplitude of the transmitted wave,

, and

, and

.

According to standard electromagnetic theory (see Appendix C), the appropriate matching conditions at the

interface (

.

According to standard electromagnetic theory (see Appendix C), the appropriate matching conditions at the

interface ( ) are that

) are that  and

and  are both continuous. Thus,

continuity of

are both continuous. Thus,

continuity of  yields

yields

gives

gives

.

It follows that

.

It follows that

, is defined as the ratio of the reflected to the incident energy

flux, so that

Likewise, the coefficient of transmission,

, is defined as the ratio of the reflected to the incident energy

flux, so that

Likewise, the coefficient of transmission,  , is the ratio of the

transmitted to the incident energy flux, so that

, is the ratio of the

transmitted to the incident energy flux, so that

then

then  and

and  .

In other words, if the two media have the same indices of refraction then

there is no reflection at the interface between them, and the transmitted

wave is consequently equal in amplitude to the incident wave. On the other

hand, if

.

In other words, if the two media have the same indices of refraction then

there is no reflection at the interface between them, and the transmitted

wave is consequently equal in amplitude to the incident wave. On the other

hand, if

then there is always some reflection at the interface. Indeed,

the amplitude of the reflected wave is roughly proportional to the difference between

then there is always some reflection at the interface. Indeed,

the amplitude of the reflected wave is roughly proportional to the difference between  and

and  . This has important practical consequences.

We can only see a clean pane of glass in a window because some of the light incident

on an air/glass interface is reflected, as a consequence of the different refractive indices

of air and glass. As is well-known, it is a lot more difficult to see glass when it is submerged in water. This is because the refractive indices of glass and water are quite similar, and so there is very little reflection of light

incident on a water/glass interface.

. This has important practical consequences.

We can only see a clean pane of glass in a window because some of the light incident

on an air/glass interface is reflected, as a consequence of the different refractive indices

of air and glass. As is well-known, it is a lot more difficult to see glass when it is submerged in water. This is because the refractive indices of glass and water are quite similar, and so there is very little reflection of light

incident on a water/glass interface.

when

when  .

The negative sign indicates a

.

The negative sign indicates a  radian phase shift of the (electric component of the) reflected wave, with

respect to the incident wave. We conclude that there is a

radian phase shift of the (electric component of the) reflected wave, with

respect to the incident wave. We conclude that there is a  radian phase shift of the reflected wave, relative to the incident wave, on reflection from an

interface with a

medium of greater refractive index. Conversely, there is zero

phase shift

on reflection from an interface with a medium of lesser refractive index. (This effect is important in thin-film interference. See Section 10.5.)

radian phase shift of the reflected wave, relative to the incident wave, on reflection from an

interface with a

medium of greater refractive index. Conversely, there is zero

phase shift

on reflection from an interface with a medium of lesser refractive index. (This effect is important in thin-film interference. See Section 10.5.)