Next: Equilibrium Between Phases

Up: Multi-Phase Systems

Previous: Equilibrium of Constant-Temperature Constant-Pressure

Stability of Single-Phase Substance

Consider a system in a single phase (e.g., a liquid or a solid). Let us focus attention on a small, but

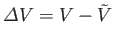

macroscopic part,  , of this system. Here,

, of this system. Here,  consists of a fixed number of particles,

consists of a fixed number of particles,  . The remainder of the system is,

relatively, very large, and, therefore, acts like a reservoir held at some constant temperature,

. The remainder of the system is,

relatively, very large, and, therefore, acts like a reservoir held at some constant temperature,  , and constant pressure,

, and constant pressure,  .

According to Equation (9.25), the condition for stable equilibrium, applied to

.

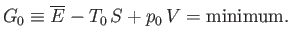

According to Equation (9.25), the condition for stable equilibrium, applied to  , is

, is

|

(9.30) |

Let the temperature,  , and the volume,

, and the volume,  , be the two independent parameters that specify the

macrostate of

, be the two independent parameters that specify the

macrostate of  . Consider, first, a situation where

. Consider, first, a situation where  is fixed, but

is fixed, but  is allowed to vary. Suppose that the minimum of

is allowed to vary. Suppose that the minimum of  occurs for

occurs for

, when

, when

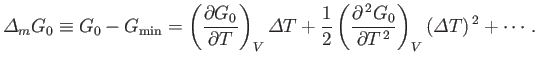

. Expanding

. Expanding  about its minimum, and writing

about its minimum, and writing

, we obtain

, we obtain

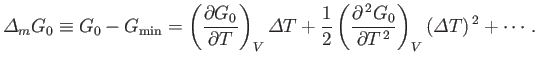

|

(9.31) |

Here, all derivatives are evaluated at

. Because

. Because

is a stationary point (i.e., a maximum or a minimum),

is a stationary point (i.e., a maximum or a minimum),

to first order in

to first order in

.

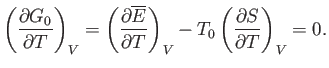

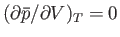

In other words,

.

In other words,

Furthermore, because  is a minimum, rather than a maximum,

is a minimum, rather than a maximum,

to second order in

to second order in

. In other words,

. In other words,

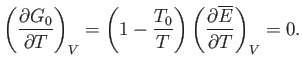

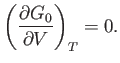

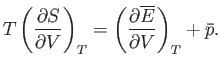

According to Equation (9.30), the condition, (9.32), that  be stationary yields

be stationary yields

|

(9.34) |

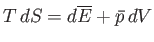

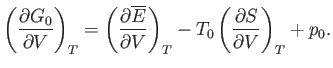

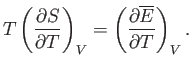

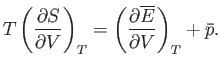

However, the fundamental thermodynamic relation

|

(9.35) |

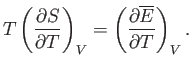

implies that if  is fixed then

is fixed then

|

(9.36) |

Thus, Equation (9.34) becomes

|

(9.37) |

Recalling that the derivatives are evaluated at

, we get

, we get

|

(9.38) |

Thus, we arrive at the rather obvious conclusion that a necessary condition for equilibrium is that the temperature of the subsystem  be the same as

that of the surrounding medium.

be the same as

that of the surrounding medium.

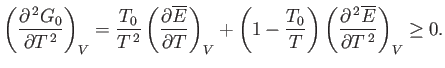

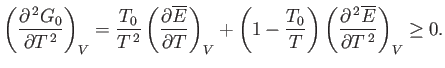

Equations (9.33) and (9.37) imply that

|

(9.39) |

Recalling that the derivatives are evaluated at

, and that

, and that

, the second term on the right-hand side of

the previous equation vanishes, and we obtain

, the second term on the right-hand side of

the previous equation vanishes, and we obtain

|

(9.40) |

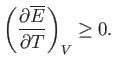

However, this derivative is simply the heat capacity,  , at constant volume. Thus, we deduce that a fundamental

criterion for the stability of any phase is

, at constant volume. Thus, we deduce that a fundamental

criterion for the stability of any phase is

|

(9.41) |

The previous condition is a particular example of a very general rule, known as Le Chátelier's principle, which states that

If a system is in a stable equilibrium then any spontaneous change of its parameters must give rise to processes that tend to

restore the system to equilibrium.

To show how this principle applies to the present case, suppose that the temperature,  , of the subsystem

, of the subsystem  has increased

above that of its surroundings,

has increased

above that of its surroundings,  , as a result of a spontaneous fluctuation. The process brought into play is the spontaneous flow of heat

from system

, as a result of a spontaneous fluctuation. The process brought into play is the spontaneous flow of heat

from system  , at the higher temperature, to its surroundings

, at the higher temperature, to its surroundings  , which brings about a decrease in the energy,

, which brings about a decrease in the energy,

, of

, of  (i.e.,

(i.e.,

). By Le Chátelier's principle, this energy decrease must act to decrease the temperature of

). By Le Chátelier's principle, this energy decrease must act to decrease the temperature of

(i.e.,

(i.e.,

), so as to restore

), so as to restore  to its equilibrium state (in which its temperature is the same as its surroundings). Hence, it follows that

to its equilibrium state (in which its temperature is the same as its surroundings). Hence, it follows that

and

and

have the same sign, so

that

have the same sign, so

that

, in agreement with Equation (9.40).

, in agreement with Equation (9.40).

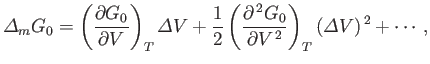

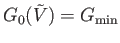

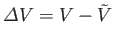

Suppose, now, that the temperature of subsystem  is fixed at

is fixed at  , but that its volume,

, but that its volume,  , is allowed to

vary. We can write

, is allowed to

vary. We can write

|

(9.42) |

where

, and the expansion is about the volume

, and the expansion is about the volume

at which

at which  attains its

minimum value. The condition that

attains its

minimum value. The condition that  is stationary yields

is stationary yields

|

(9.43) |

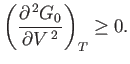

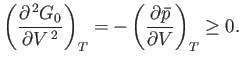

The condition that the stationary point is a minimum gives

|

(9.44) |

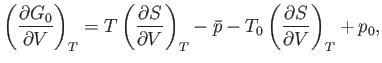

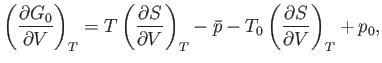

Making use of Equation (9.30), we get

|

(9.45) |

However, Equation (9.35) implies that

|

(9.46) |

Hence,

|

(9.47) |

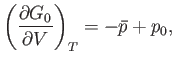

or

|

(9.48) |

because  . Thus, the condition (9.43) yields

. Thus, the condition (9.43) yields

|

(9.49) |

This rather obvious result states that in equilibrium the pressure of subsystem  must be equal to that of the surrounding medium.

must be equal to that of the surrounding medium.

Equations (9.44) and (9.48) imply that

|

(9.50) |

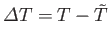

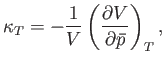

When expressed in terms of the isothermal compressibility,

|

(9.51) |

the stability criterion (9.50) is equivalent to

|

(9.52) |

To show how the preceding stability condition is consistent with Le Chátelier's principle, suppose that the volume of subsystem

has increased by an amount

has increased by an amount

, as a result of a spontaneous fluctuation. The pressure,

, as a result of a spontaneous fluctuation. The pressure,  , of

, of  must then

decrease below that of its surroundings (i.e.,

must then

decrease below that of its surroundings (i.e.,

) in order to ensure that the net force exerted on

) in order to ensure that the net force exerted on  by

its surroundings is such as to reduce the volume of

by

its surroundings is such as to reduce the volume of  back towards its equilibrium value. In other words,

back towards its equilibrium value. In other words,

and

and

must have opposite signs, implying that

must have opposite signs, implying that

.

.

The preceding discussion allows us to characterize the spontaneous volume fluctuations of the small subsystem  . The

most probable situation is that where

. The

most probable situation is that where  takes the value

takes the value  that minimizes

that minimizes  , so that

, so that

.

Let

.

Let  denote the probability that the volume of

denote the probability that the volume of  lies between

lies between  and

and  . According to Equation (9.29),

. According to Equation (9.29),

![$\displaystyle P(V) dV \propto \exp\left[-\frac{G_0(V)}{k T_0}\right] dV.$](img2697.png) |

(9.53) |

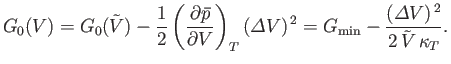

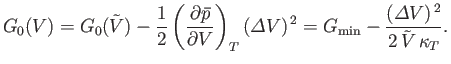

However, when

is small, the expansion (9.42) is applicable. By virtue of Equations (9.43), (9.50),

and (9.51), the expansion yields

is small, the expansion (9.42) is applicable. By virtue of Equations (9.43), (9.50),

and (9.51), the expansion yields

|

(9.54) |

Thus, Equation (9.53) becomes

![$\displaystyle P(V) dV =B\exp\left[-\frac{(V-\tilde{V})^{ 2}}{2 k T_0 \kappa_T \tilde{V}}\right]dV,$](img2699.png) |

(9.55) |

where we have absorbed

into the constant of proportionality,

into the constant of proportionality,  . Of course,

. Of course,  can be determined via the requirement that

the integral of

can be determined via the requirement that

the integral of  over all possible values of the volume,

over all possible values of the volume,  , be equal to unity.

, be equal to unity.

The probability distribution (9.55) is a Gaussian whose maximum lies at

. Thus,

. Thus,  is equal to the

mean volume,

is equal to the

mean volume,

. Moreover, the standard deviation of the spontaneous fluctuations of

. Moreover, the standard deviation of the spontaneous fluctuations of  about its mean value is

about its mean value is

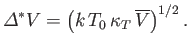

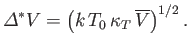

|

(9.56) |

(See Section 2.9.)

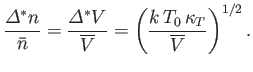

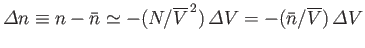

The fluctuations in  imply corresponding fluctuations in the number of particles per unit volume,

imply corresponding fluctuations in the number of particles per unit volume,  , (and, hence, in the mean

density) of the subsystem

, (and, hence, in the mean

density) of the subsystem  . The fluctuations in

. The fluctuations in  are centered on the mean value

are centered on the mean value

. For relatively

small fluctuations,

. For relatively

small fluctuations,

.

Hence,

.

Hence,

|

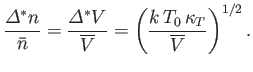

(9.57) |

Note that the relative magnitudes of the density and volume fluctuations are inversely proportional to the

square-root of the volume,

, under consideration.

, under consideration.

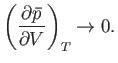

An interesting situation arises when

|

(9.58) |

In this limit,

, and the density fluctuations become very large. [They do not, however, become infinite,

because the neglect of third-order, and higher, terms in the expansion (9.42) is no longer justified.]

The condition

, and the density fluctuations become very large. [They do not, however, become infinite,

because the neglect of third-order, and higher, terms in the expansion (9.42) is no longer justified.]

The condition

defines the so-called critical point of the substance, at which the

distinction between its liquid and gas phases disappears. (See Section 9.10.) The very large density fluctuations at the critical

point lead to strong scattering of light. As a result, a substance that is ordinarily transparent will assume a milky-white

appearance at its critical point (e.g.,

defines the so-called critical point of the substance, at which the

distinction between its liquid and gas phases disappears. (See Section 9.10.) The very large density fluctuations at the critical

point lead to strong scattering of light. As a result, a substance that is ordinarily transparent will assume a milky-white

appearance at its critical point (e.g.,

when it approaches its critical point at 304K and 73 atmospheres). This interesting

phenomenon is called critical-point opalecance.

when it approaches its critical point at 304K and 73 atmospheres). This interesting

phenomenon is called critical-point opalecance.

Next: Equilibrium Between Phases

Up: Multi-Phase Systems

Previous: Equilibrium of Constant-Temperature Constant-Pressure

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-25

![]() , and the volume,

, and the volume, ![]() , be the two independent parameters that specify the

macrostate of

, be the two independent parameters that specify the

macrostate of ![]() . Consider, first, a situation where

. Consider, first, a situation where ![]() is fixed, but

is fixed, but ![]() is allowed to vary. Suppose that the minimum of

is allowed to vary. Suppose that the minimum of ![]() occurs for

occurs for

![]() , when

, when

![]() . Expanding

. Expanding ![]() about its minimum, and writing

about its minimum, and writing

![]() , we obtain

, we obtain

![]() be stationary yields

be stationary yields

![]() is fixed at

is fixed at ![]() , but that its volume,

, but that its volume, ![]() , is allowed to

vary. We can write

, is allowed to

vary. We can write

![]() has increased by an amount

has increased by an amount

![]() , as a result of a spontaneous fluctuation. The pressure,

, as a result of a spontaneous fluctuation. The pressure, ![]() , of

, of ![]() must then

decrease below that of its surroundings (i.e.,

must then

decrease below that of its surroundings (i.e.,

![]() ) in order to ensure that the net force exerted on

) in order to ensure that the net force exerted on ![]() by

its surroundings is such as to reduce the volume of

by

its surroundings is such as to reduce the volume of ![]() back towards its equilibrium value. In other words,

back towards its equilibrium value. In other words,

![]() and

and

![]() must have opposite signs, implying that

must have opposite signs, implying that

![]() .

.

![]() . The

most probable situation is that where

. The

most probable situation is that where ![]() takes the value

takes the value ![]() that minimizes

that minimizes ![]() , so that

, so that

![]() .

Let

.

Let ![]() denote the probability that the volume of

denote the probability that the volume of ![]() lies between

lies between ![]() and

and ![]() . According to Equation (9.29),

. According to Equation (9.29),

![]() . Thus,

. Thus, ![]() is equal to the

mean volume,

is equal to the

mean volume,

![]() . Moreover, the standard deviation of the spontaneous fluctuations of

. Moreover, the standard deviation of the spontaneous fluctuations of ![]() about its mean value is

about its mean value is