Next: Exercises

Up: Quantum Statistics

Previous: Neutron Stars

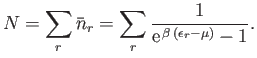

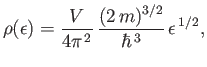

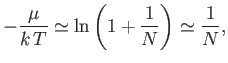

Consider a gas of weakly-interacting bosons. It is helpful to define the gas's chemical potential,

|

(8.221) |

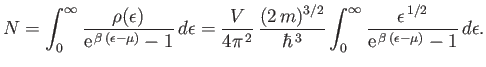

whose value is determined by the equation

|

(8.222) |

Here,  is the total number of particles, and

is the total number of particles, and

the energy of the single-particle

quantum state

the energy of the single-particle

quantum state  .

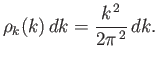

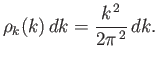

Because, in general, the energies of the quantum states are very closely spaced, the sum in the previous expression can

approximated as an integral. Now, according to Section 8.12, the number of quantum states per unit volume

with wavenumbers in the range

.

Because, in general, the energies of the quantum states are very closely spaced, the sum in the previous expression can

approximated as an integral. Now, according to Section 8.12, the number of quantum states per unit volume

with wavenumbers in the range  to

to  is

is

|

(8.223) |

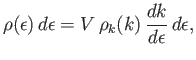

However, the energy of a state with wavenumber  is

is

|

(8.224) |

where  is the boson mass. Let

is the boson mass. Let

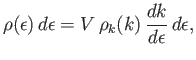

be the number of bosons

whose energies lies in the range

be the number of bosons

whose energies lies in the range  to

to

. It follows that

. It follows that

|

(8.225) |

where  is the volume of the gas.

Here, we are assuming that the bosons are spinless, so that there is only one particle state per translational state.

Hence,

is the volume of the gas.

Here, we are assuming that the bosons are spinless, so that there is only one particle state per translational state.

Hence,

|

(8.226) |

and Equation (8.222) becomes

|

(8.227) |

However, there is a significant flaw in this formulation. In using the integral approximation, rather than performing the sum, the ground-state,

, has

been left out [because

, has

been left out [because  ]. Under ordinary circumstances, this omission does not matter. However, at very low temperatures, bosons tend to condense into

the ground-state, and the occupation number of this state becomes very much larger than that of any other state. Under these circumstances, the ground-state must be included

in the calculation.

]. Under ordinary circumstances, this omission does not matter. However, at very low temperatures, bosons tend to condense into

the ground-state, and the occupation number of this state becomes very much larger than that of any other state. Under these circumstances, the ground-state must be included

in the calculation.

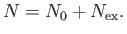

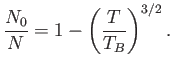

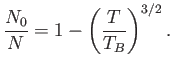

We can overcome the previous difficulty in the following manner. Let there be  bosons in the ground-state, and

bosons in the ground-state, and

in the

various excited states, so that

in the

various excited states, so that

|

(8.228) |

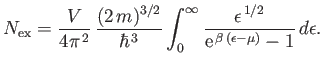

Because the ground-state is excluded from expression (8.227), the integral only gives the number of bosons in excited states.

In other words,

|

(8.229) |

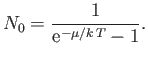

Now, because the ground-state has zero energy, its mean occupancy number is

|

(8.230) |

Moreover, at temperatures very close to absolute zero, we expect

, which implies that

, which implies that

|

(8.231) |

We conclude that

|

(8.232) |

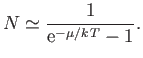

for large  . Hence, at very low temperatures, we can safely set

. Hence, at very low temperatures, we can safely set

equal to unity in Equation (8.229).

Thus, we obtain

equal to unity in Equation (8.229).

Thus, we obtain

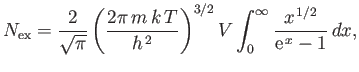

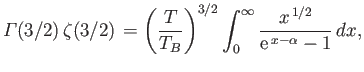

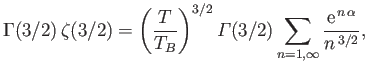

|

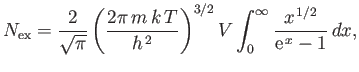

(8.233) |

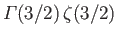

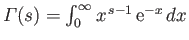

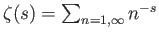

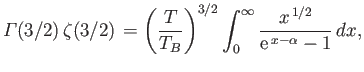

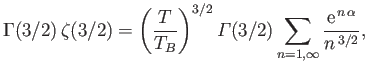

where

. The value of the integral is

. The value of the integral is

, where

, where

is a Gamma

function, and

is a Gamma

function, and

a Riemann zeta function. (See Exercise 4.) Furthermore,

a Riemann zeta function. (See Exercise 4.) Furthermore,

,

and

,

and

. Hence,

. Hence,

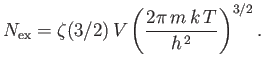

|

(8.234) |

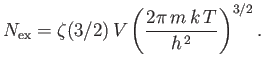

The so-called Bose temperature,  , is defined as the temperature above which all the bosons are in excited states.

Setting

, is defined as the temperature above which all the bosons are in excited states.

Setting

and

and  in the previous expression, we obtain

in the previous expression, we obtain

![$\displaystyle T_B = \frac{h^{ 2}}{2\pi m k}\left[\frac{N}{\zeta(3/2) V}\right]^{ 2/3}.$](img2430.png) |

(8.235) |

Moreover,

|

(8.236) |

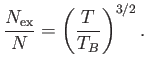

Thus, the fractional number of bosons in the ground-state is

|

(8.237) |

Obviously, the preceding two equations are only valid for  . For

. For  , we have

, we have  and

and

.

Moreover, for

.

Moreover, for  we have

we have

, whereas for

, whereas for  , combining Equations (8.229) (with

, combining Equations (8.229) (with

) and (8.235)

yields

) and (8.235)

yields

|

(8.238) |

where

and

and

. Expanding in powers of

. Expanding in powers of

, we obtain

, we obtain

|

(8.239) |

where  (see Exercise 4), which reduces to

(see Exercise 4), which reduces to

|

(8.240) |

The previous equation can be solved numerically to give

as a function of

as a function of  .

.

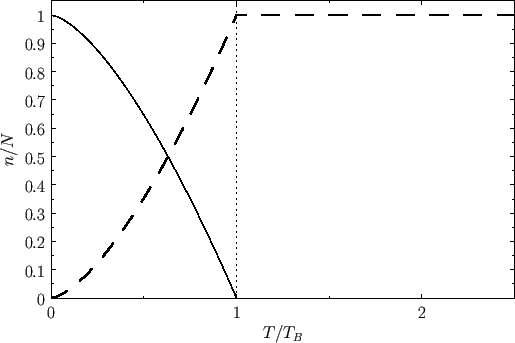

Figure:

Variation with temperature of  (solid curve) and

(solid curve) and

(dashed curve) for a boson gas.

(dashed curve) for a boson gas.

|

Let us estimate a typical value of the Bose temperature. Consider a boson gas made up of

atoms confined to a volume of 1 litre. The mass

of a

atoms confined to a volume of 1 litre. The mass

of a

atom is

atom is

. Making use of Equation (8.235), we

obtain

. Making use of Equation (8.235), we

obtain

![$\displaystyle T_B = \frac{(6.63\times 10^{-34})^{ 2}}{2\pi (6.65\times 10^{-2...

....02\times 10^{ 22}}{(2.612) (1\times 10^{-3})}\right]^{ 2/3}=0.062 {\rm K}.$](img2449.png) |

(8.241) |

At atmospheric pressure, helium liquifies at

, long before the Bose temperature is reached. In fact, all real gases liquify before the Bose temperature is reached.

, long before the Bose temperature is reached. In fact, all real gases liquify before the Bose temperature is reached.

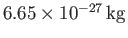

Figure:

Variation with temperature of

for a boson gas.

for a boson gas.

|

Figure 8.7 shows the variation of  and

and

with

with  . A corresponding graph of

. A corresponding graph of

[numerically determined from Equation (8.240) when

[numerically determined from Equation (8.240) when  ] is shown in Figure 8.8. The sudden collapse

of bosons into the ground-state at temperatures below the Bose temperature is known as Bose-Einstein condensation. In

1995, E.A. Cornell and C.E. Wieman led a team of physicists that created a nearly pure condensate by cooling a vapor of rubidium atoms to a temperature of

] is shown in Figure 8.8. The sudden collapse

of bosons into the ground-state at temperatures below the Bose temperature is known as Bose-Einstein condensation. In

1995, E.A. Cornell and C.E. Wieman led a team of physicists that created a nearly pure condensate by cooling a vapor of rubidium atoms to a temperature of

. (Cornell and Wieman were subsequently awarded the Nobel prize in 2001.)

. (Cornell and Wieman were subsequently awarded the Nobel prize in 2001.)

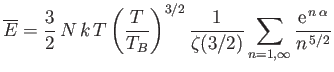

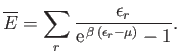

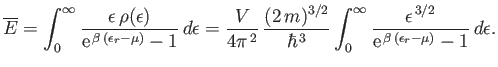

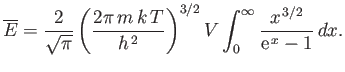

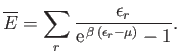

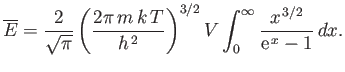

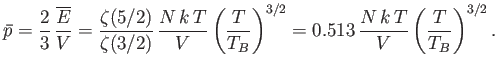

The mean energy of a boson gas takes the form

|

(8.242) |

As before, we can approximate the sum as an integral, and write

|

(8.243) |

In this case, we do not need to worry about the omission of the ground-state in the integral, because this state makes no contribution to the mean

energy (because

in the ground-state). For temperatures above the Bose temperature, all the bosons

are in excited states, and we expect the mean energy to approach the classical value,

in the ground-state). For temperatures above the Bose temperature, all the bosons

are in excited states, and we expect the mean energy to approach the classical value,

. However, below the

Bose temperature, a substantial fraction of bosons are in the ground-state, so we expect the mean energy to fall well below the

classical value.

. However, below the

Bose temperature, a substantial fraction of bosons are in the ground-state, so we expect the mean energy to fall well below the

classical value.

As we have seen, the chemical potential of a boson gas is very close to zero for temperatures below the Bose temperature. Hence,

setting  in the previous expression, and making the substitution

in the previous expression, and making the substitution

, we obtain

, we obtain

|

(8.244) |

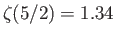

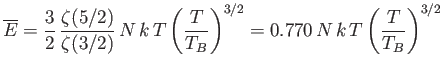

The integral is equal to

, where

, where

, and

, and

. (See Exercise 4.)

Thus, we obtain

. (See Exercise 4.)

Thus, we obtain

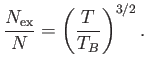

|

(8.245) |

where use has been made of Equation (8.235). Note that

for temperatures below the Bose temperature, but

that

for temperatures below the Bose temperature, but

that

becomes similar in magnitude to the classical value,

becomes similar in magnitude to the classical value,

, as

, as

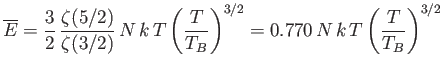

. The molar specific heat below the Bose temperature is

. The molar specific heat below the Bose temperature is

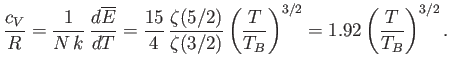

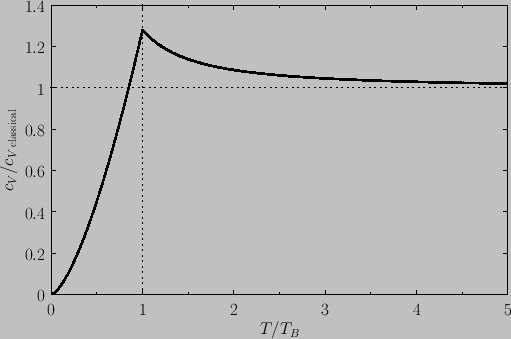

|

(8.246) |

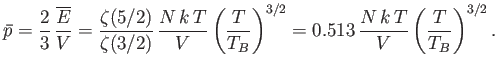

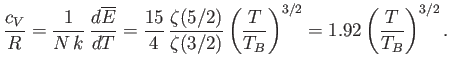

Likewise, the mean pressure is

|

(8.247) |

(See Exercise 7.) In both cases, the quantities become similar in magnitude to their classical values as

, but

fall far below these values when

, but

fall far below these values when  .

.

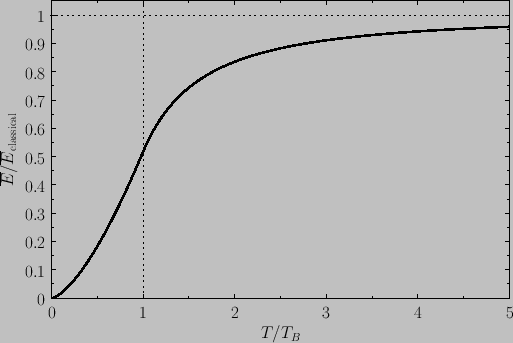

Figure:

Variation with temperature of

for a boson gas, where

for a boson gas, where

.

.

|

For  , Equation (8.243) becomes

, Equation (8.243) becomes

|

(8.248) |

(see Exercise 4), where  is determined from the numerical solution of Equation (8.240). Figure 8.9 shows how

the mean energy of a boson gas varies with temperature, and clearly illustrates that the energy approaches

its classical value asymptotically in the limit

is determined from the numerical solution of Equation (8.240). Figure 8.9 shows how

the mean energy of a boson gas varies with temperature, and clearly illustrates that the energy approaches

its classical value asymptotically in the limit  . Finally, Figure 8.10 shows how the molar heat capacity of a boson gas

varies with temperature. It can be seen that the

. Finally, Figure 8.10 shows how the molar heat capacity of a boson gas

varies with temperature. It can be seen that the  curve has a change in slope at

curve has a change in slope at  , reaching a maximum value there of

, reaching a maximum value there of

. At higher temperatures,

. At higher temperatures,  approaches the classical value,

approaches the classical value,  , asymptotically.

, asymptotically.

Figure:

Variation with temperature of

for a boson gas, where

for a boson gas, where

.

.

|

Next: Exercises

Up: Quantum Statistics

Previous: Neutron Stars

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-25

![]() bosons in the ground-state, and

bosons in the ground-state, and

![]() in the

various excited states, so that

in the

various excited states, so that

![]() , is defined as the temperature above which all the bosons are in excited states.

Setting

, is defined as the temperature above which all the bosons are in excited states.

Setting

![]() and

and ![]() in the previous expression, we obtain

in the previous expression, we obtain

![]()

![]() atoms confined to a volume of 1 litre. The mass

of a

atoms confined to a volume of 1 litre. The mass

of a

![]() atom is

atom is

![]() . Making use of Equation (8.235), we

obtain

. Making use of Equation (8.235), we

obtain

![$\displaystyle T_B = \frac{(6.63\times 10^{-34})^{ 2}}{2\pi (6.65\times 10^{-2...

....02\times 10^{ 22}}{(2.612) (1\times 10^{-3})}\right]^{ 2/3}=0.062 {\rm K}.$](img2449.png)

![]() and

and

![]() with

with ![]() . A corresponding graph of

. A corresponding graph of

![]() [numerically determined from Equation (8.240) when

[numerically determined from Equation (8.240) when ![]() ] is shown in Figure 8.8. The sudden collapse

of bosons into the ground-state at temperatures below the Bose temperature is known as Bose-Einstein condensation. In

1995, E.A. Cornell and C.E. Wieman led a team of physicists that created a nearly pure condensate by cooling a vapor of rubidium atoms to a temperature of

] is shown in Figure 8.8. The sudden collapse

of bosons into the ground-state at temperatures below the Bose temperature is known as Bose-Einstein condensation. In

1995, E.A. Cornell and C.E. Wieman led a team of physicists that created a nearly pure condensate by cooling a vapor of rubidium atoms to a temperature of

![]() . (Cornell and Wieman were subsequently awarded the Nobel prize in 2001.)

. (Cornell and Wieman were subsequently awarded the Nobel prize in 2001.)

![]() in the previous expression, and making the substitution

in the previous expression, and making the substitution

![]() , we obtain

, we obtain

![]() , Equation (8.243) becomes

, Equation (8.243) becomes