Next: Harmonic Perturbations

Up: Time-Dependent Perturbation Theory

Previous: Sudden Perturbations

Energy-Shifts and Decay-Widths

We have examined how a state  , other than the initial

state

, other than the initial

state  , becomes populated as a result of some time-dependent

perturbation applied to the system. Let us now consider

how the initial state becomes depopulated.

, becomes populated as a result of some time-dependent

perturbation applied to the system. Let us now consider

how the initial state becomes depopulated.

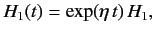

In this case, it is convenient to gradually turn on the perturbation from zero at

. Thus,

. Thus,

|

(821) |

where  is small and positive, and

is small and positive, and  is a constant.

is a constant.

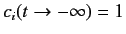

In the remote past,

, the system is assumed to

be in the initial state

, the system is assumed to

be in the initial state  . Thus,

. Thus,

,

and

,

and

. Basically, we want to

calculate the time evolution of the coefficient

. Basically, we want to

calculate the time evolution of the coefficient  .

First, however, let us check that our previous Fermi golden rule result

still applies when the perturbing potential is turned on slowly,

instead of very suddenly. For

.

First, however, let us check that our previous Fermi golden rule result

still applies when the perturbing potential is turned on slowly,

instead of very suddenly. For

we have from Equations (795)-(796) that

we have from Equations (795)-(796) that

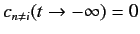

where

.

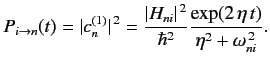

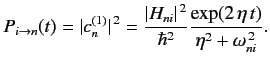

It follows that, to first order, the transition probability from state

.

It follows that, to first order, the transition probability from state  to state

to state  is

is

|

(824) |

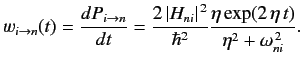

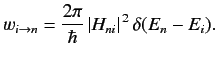

The transition rate is given by

|

(825) |

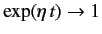

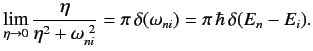

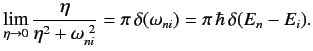

Consider the limit

. In this limit,

. In this limit,

, but

, but

|

(826) |

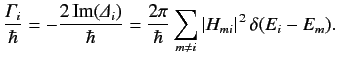

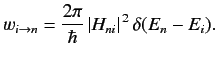

Thus, Equation (825) yields the standard Fermi golden rule result

|

(827) |

It is clear that the delta-function in the above formula actually represents

a function that is highly peaked at some particular energy. The width

of the peak is determined by how fast the perturbation is switched on.

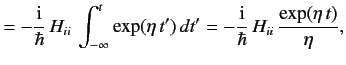

Let us now calculate  using Equations (795)-(797). We have

using Equations (795)-(797). We have

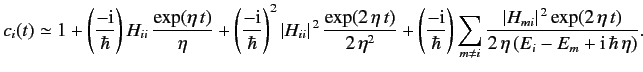

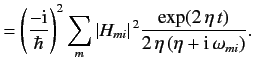

Thus, to second order we have

|

(831) |

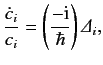

Let us now consider the ratio

, where

, where

. Using Equation (831), we can evaluate this ratio in the limit

. Using Equation (831), we can evaluate this ratio in the limit

. We obtain

. We obtain

This result is formally correct to second order in perturbed quantities.

Note that the right-hand side of Equation (832) is independent of time.

We can write

|

(833) |

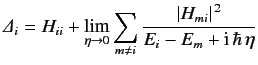

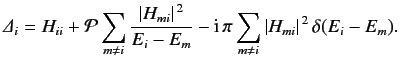

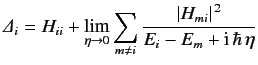

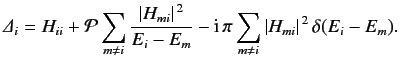

where

|

(834) |

is a constant.

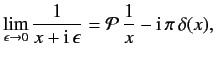

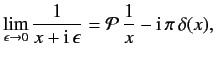

According to a well-known result in pure mathematics,

|

(835) |

where

, and

, and  denotes the principal part.

It follows that

denotes the principal part.

It follows that

|

(836) |

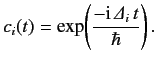

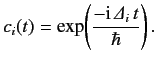

It is convenient to normalize the solution of

Equation (833) such that

. Thus, we obtain

. Thus, we obtain

|

(837) |

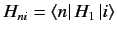

According to Equation (744), the time evolution of the initial

state ket  is given by

is given by

![$\displaystyle \vert i, t\rangle = \exp[-{\rm i}\,({\mit\Delta}_i + E_i)\,t/\hbar] \,\vert i\rangle.$](img1978.png) |

(838) |

We can rewrite this result as

![$\displaystyle \vert i, t\rangle = \exp(-{\rm i}\,[E_i + {\rm Re}({\mit\Delta}_i)\,]\,t/\hbar)\, \exp[\,{\rm Im}({\mit\Delta}_i)\,t/\hbar] \,\vert i\rangle.$](img1979.png) |

(839) |

It is clear that the real part of

gives rise to a simple

shift in energy of state

gives rise to a simple

shift in energy of state  , whereas the imaginary part of

, whereas the imaginary part of

governs the growth or decay of this state.

Thus,

governs the growth or decay of this state.

Thus,

![$\displaystyle \vert i, t\rangle = \exp[-{\rm i}\,(E_i + {\mit\Delta} E_i)\,t/\hbar] \exp( - {\mit\Gamma}_i\,t/2\,\hbar)\,\vert i\rangle,$](img1981.png) |

(840) |

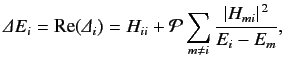

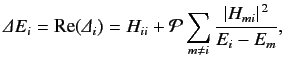

where

|

(841) |

and

|

(842) |

Note that the energy-shift

is the same as that predicted

by standard time-independent perturbation theory.

is the same as that predicted

by standard time-independent perturbation theory.

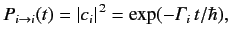

The probability of observing the system in state  at time

at time  , given

that it is definately in state

, given

that it is definately in state  at time

at time  , is given by

, is given by

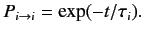

|

(843) |

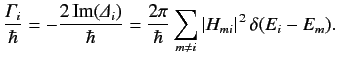

where

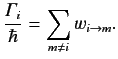

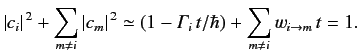

|

(844) |

Here, use has been made of Equation (817).

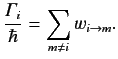

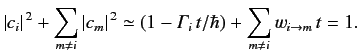

Clearly, the rate of decay of the initial state is a simple function of

the transition rates to the other states. Note that the system conserves

probability up to second order in perturbed quantities, because

|

(845) |

The quantity

is called the decay-width of state

is called the decay-width of state  .

It is

closely related to the mean lifetime of this state,

.

It is

closely related to the mean lifetime of this state,

|

(846) |

where

|

(847) |

According to Equation (839), the amplitude of state  both oscillates

and decays as time progresses. Clearly, state

both oscillates

and decays as time progresses. Clearly, state  is not a

stationary state in the presence of the time-dependent perturbation.

However, we can still represent it as a superposition of stationary

states (whose amplitudes simply oscillate in time). Thus,

is not a

stationary state in the presence of the time-dependent perturbation.

However, we can still represent it as a superposition of stationary

states (whose amplitudes simply oscillate in time). Thus,

![$\displaystyle \exp[-{\rm i}\,(E_i + {\mit\Delta} E_i)\,t/\hbar] \exp( - {\mit\Gamma}_i\,t/2\,\hbar) = \int dE\,f(E) \exp(-{\rm i}\, E\,t/\hbar),$](img1991.png) |

(848) |

where  is the weight of the stationary state with energy

is the weight of the stationary state with energy  in the

superposition. The Fourier inversion theorem yields

in the

superposition. The Fourier inversion theorem yields

![$\displaystyle \vert f(E)\vert^{\,2} \propto \frac{1}{(E - [E_i +{\rm Re}({\mit\Delta}_i)])^2 + {\mit\Gamma}_i^{\,2}/4}.$](img1993.png) |

(849) |

In the absence of the perturbation,

is basically a delta-function

centered on the unperturbed energy

is basically a delta-function

centered on the unperturbed energy  of state

of state  .

In other words, state

.

In other words, state  is a stationary state whose energy is

completely determined. In the presence of the perturbation, the energy

of state

is a stationary state whose energy is

completely determined. In the presence of the perturbation, the energy

of state  is shifted by

is shifted by

. The fact that

the state is no longer stationary (i.e., it decays in time) implies that

its energy cannot be exactly determined. Indeed, the

energy of the state

is smeared over some region of width (in energy)

. The fact that

the state is no longer stationary (i.e., it decays in time) implies that

its energy cannot be exactly determined. Indeed, the

energy of the state

is smeared over some region of width (in energy)

centered

around the shifted energy

centered

around the shifted energy

. The faster the

decay of the state (i.e., the larger

. The faster the

decay of the state (i.e., the larger

), the more its

energy is spread out. This effect is clearly a manifestation of

the energy-time uncertainty relation

), the more its

energy is spread out. This effect is clearly a manifestation of

the energy-time uncertainty relation

.

One consequence of this effect is the existence of a natural

width of spectral lines associated with the decay of some excited

state to the ground state (or any other lower energy state). The uncertainty

in energy of the excited state, due to its propensity to decay, gives

rise to a slight smearing (in wavelength)

of the spectral line associated with the

transition. Strong lines, which correspond to fast transitions, are smeared out

more that weak lines. For this reason, spectroscopists generally favor

forbidden lines (see Section 8.10) for Doppler-shift measurements. Such lines are not as bright

as those corresponding to allowed transitions, but they are a lot sharper.

.

One consequence of this effect is the existence of a natural

width of spectral lines associated with the decay of some excited

state to the ground state (or any other lower energy state). The uncertainty

in energy of the excited state, due to its propensity to decay, gives

rise to a slight smearing (in wavelength)

of the spectral line associated with the

transition. Strong lines, which correspond to fast transitions, are smeared out

more that weak lines. For this reason, spectroscopists generally favor

forbidden lines (see Section 8.10) for Doppler-shift measurements. Such lines are not as bright

as those corresponding to allowed transitions, but they are a lot sharper.

Next: Harmonic Perturbations

Up: Time-Dependent Perturbation Theory

Previous: Sudden Perturbations

Richard Fitzpatrick

2013-04-08

![]() . Thus,

. Thus,

![]() , the system is assumed to

be in the initial state

, the system is assumed to

be in the initial state ![]() . Thus,

. Thus,

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() . Basically, we want to

calculate the time evolution of the coefficient

. Basically, we want to

calculate the time evolution of the coefficient ![]() .

First, however, let us check that our previous Fermi golden rule result

still applies when the perturbing potential is turned on slowly,

instead of very suddenly. For

.

First, however, let us check that our previous Fermi golden rule result

still applies when the perturbing potential is turned on slowly,

instead of very suddenly. For

![]() we have from Equations (795)-(796) that

we have from Equations (795)-(796) that

![$\displaystyle = - \frac{\rm i}{\hbar}\, H_{ni} \int_{-\infty}^t dt'\, \exp[(\et...

..., \frac{ \exp[(\eta + {\rm i}\,\omega_{ni} )\, t]}{\eta +{\rm i}\,\omega_{ni}},$](img1950.png)

![]() using Equations (795)-(797). We have

using Equations (795)-(797). We have

![$\displaystyle = \left(\frac{-{\rm i}}{\hbar} \right)^2 \sum_m \vert H_{mi}\vert...

...xp[(\eta+ {\rm i}\,\omega_{im})\, t'] \exp[ (\eta+ {\rm i}\,\omega_{mi})\, t'']$](img1962.png)

![]() , where

, where

![]() . Using Equation (831), we can evaluate this ratio in the limit

. Using Equation (831), we can evaluate this ratio in the limit

![]() . We obtain

. We obtain

![]() . Thus, we obtain

. Thus, we obtain

![]() at time

at time ![]() , given

that it is definately in state

, given

that it is definately in state ![]() at time

at time ![]() , is given by

, is given by

![]() is called the decay-width of state

is called the decay-width of state ![]() .

It is

closely related to the mean lifetime of this state,

.

It is

closely related to the mean lifetime of this state,

![$\displaystyle \exp[-{\rm i}\,(E_i + {\mit\Delta} E_i)\,t/\hbar] \exp( - {\mit\Gamma}_i\,t/2\,\hbar) = \int dE\,f(E) \exp(-{\rm i}\, E\,t/\hbar),$](img1991.png)

![$\displaystyle \vert f(E)\vert^{\,2} \propto \frac{1}{(E - [E_i +{\rm Re}({\mit\Delta}_i)])^2 + {\mit\Gamma}_i^{\,2}/4}.$](img1993.png)