Next: Exercises

Up: Time-Independent Perturbation Theory

Previous: Zeeman Effect

Hyperfine Structure

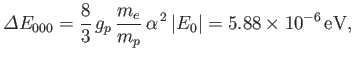

The proton in a hydrogen atom is a spin one-half charged particle, and therefore

possesses a spin magnetic moment. By analogy with Equation (5.44),

we can write

|

(7.141) |

where

is the proton magnetic

moment,

is the proton magnetic

moment,  the proton spin,

the proton spin,  the proton mass, and

the proton mass, and  the proton

the proton  -factor. The proton

-factor. The proton  -factor is found experimentally to take that value

-factor is found experimentally to take that value  [117]. [In writing the previous equation, we have made use of the fact that the proton is essentially stationary (in the center of mass frame),

and, therefore, possesses zero orbital angular momentum.] Note that the spin

magnetic moment of a proton is much smaller (by a factor of order

[117]. [In writing the previous equation, we have made use of the fact that the proton is essentially stationary (in the center of mass frame),

and, therefore, possesses zero orbital angular momentum.] Note that the spin

magnetic moment of a proton is much smaller (by a factor of order  )

than that of an electron.

)

than that of an electron.

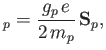

According

to classical electromagnetism, the vector potential due to a point magnetic dipole  located at the

origin is [49]

located at the

origin is [49]

|

(7.142) |

where

. The associated magnetic field takes the form [49]

. The associated magnetic field takes the form [49]

![$\displaystyle {\bf B}=\nabla\times {\bf A} =\frac{\mu_0}{4\pi}\left[ \frac{3\,({\bf M}\cdot{\bf e}_r)\,{\bf e}_r-{\bf M}}{r^{\,3}}\right],$](img2072.png) |

(7.143) |

where

. Suppose that

. Suppose that

. The

Cartesian components of

. The

Cartesian components of  are thus

are thus

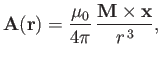

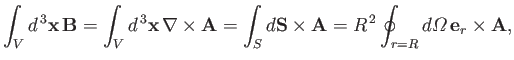

where ( ,

,  ,

,  ) are conventional spherical coordinates. It

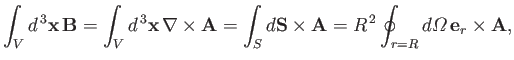

is easily demonstrated that

) are conventional spherical coordinates. It

is easily demonstrated that

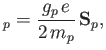

|

(7.147) |

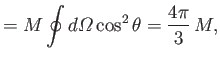

where  is a spherical volume of radius

is a spherical volume of radius  , centered on the origin. However,

we can also write [67]

, centered on the origin. However,

we can also write [67]

|

(7.148) |

where  is the bounding surface of volume

is the bounding surface of volume  , and

, and

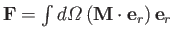

an element of solid angle. According to Equation (7.145),

an element of solid angle. According to Equation (7.145),

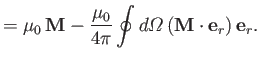

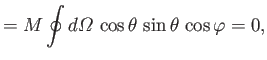

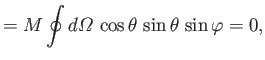

Let

, and

, and

.

It follows that

.

It follows that

which implies that

.

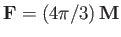

Hence, we obtain

.

Hence, we obtain

|

(7.153) |

However, the previous expression is inconsistent with Equations (7.147)-(7.149). Note that

the right-hand side of Equation (7.156) is independent of the radius,  , of the integration volume

, of the integration volume  .

Consequently, we can take the limit

.

Consequently, we can take the limit

without changing the value of

without changing the value of

.

We deduce that the non-zero contribution to this integral originates from the origin. Hence, we can

reconcile the previously mentioned inconsistency by modifying Equation (7.146) to read

.

We deduce that the non-zero contribution to this integral originates from the origin. Hence, we can

reconcile the previously mentioned inconsistency by modifying Equation (7.146) to read

![$\displaystyle {\bf B} =\frac{\mu_0}{4\pi}\left[ \frac{3\,({\bf M}\cdot{\bf e}_r...

...-{\bf M}}{r^{\,3}}\right] + \frac{2\,\mu_0}{3}\,\delta^{\,3}({\bf x})\,{\bf M}.$](img2099.png) |

(7.154) |

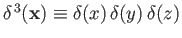

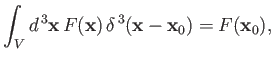

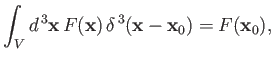

Here,

is a three-dimensional Dirac delta function. This function has the property that

is a three-dimensional Dirac delta function. This function has the property that

|

(7.155) |

where

is a general function that is well-behaved in the vicinity of

is a general function that is well-behaved in the vicinity of

(which is

assumed to lie in the volume

(which is

assumed to lie in the volume  ) [92].

) [92].

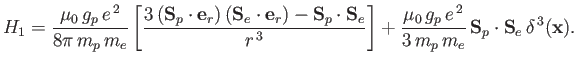

According to the previous formula, the proton's magnetic moment,

, generates a

magnetic field of the form

, generates a

magnetic field of the form

![$\displaystyle {\bf B} = \frac{\mu_0}{4\pi\,r^{\,3}}\,\left[3\,(\mbox{\boldmath$...

...p\right] + \frac{2\,\mu_0}{3}\,\delta^{\,3}({\bf x})\,\mbox{\boldmath$\mu$}_p\,$](img2104.png) |

(7.156) |

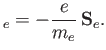

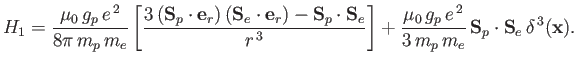

where  measures position relative to the proton. Now, the Hamiltonian of the electron in the magnetic

field generated by the proton is simply [49]

measures position relative to the proton. Now, the Hamiltonian of the electron in the magnetic

field generated by the proton is simply [49]

where

|

(7.158) |

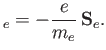

Here,

is the electron magnetic moment [see Equation (7.98)], and

is the electron magnetic moment [see Equation (7.98)], and  the electron spin. Thus, the

perturbing Hamiltonian is written

the electron spin. Thus, the

perturbing Hamiltonian is written

|

(7.159) |

Note that, because we have neglected coupling between the proton

spin and the magnetic field generated by the electron's orbital motion,

the previous expression is only valid for  states.

states.

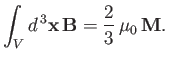

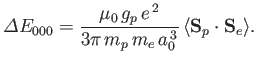

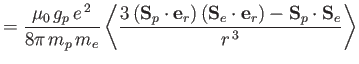

According to standard first-order perturbation theory, the energy-shift induced

by spin-spin coupling between the proton and the electron is the expectation

value of the perturbing Hamiltonian. Hence,

In the final term on the right-hand side, the expectation value is taken over the overall spin state.

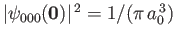

For the ground state of hydrogen, which is spherically symmetric,

the first term in the previous expression vanishes by symmetry.

Moreover, it is easily demonstrated that

. Thus, we obtain

. Thus, we obtain

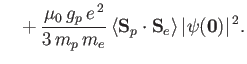

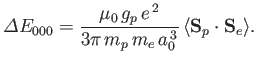

|

(7.161) |

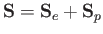

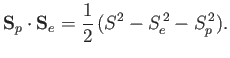

Let

|

(7.162) |

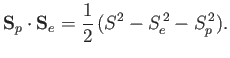

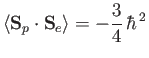

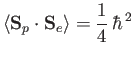

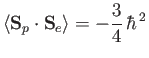

be the total spin. We can show that

|

(7.163) |

Thus, the simultaneous eigenstates of the perturbing Hamiltonian

and the main Hamiltonian are the simultaneous eigenstates of  ,

,

, and

, and  . (The use of simultaneous eigenstates of the perturbing and main Hamiltonian

avoids the possibility of singular terms arising in the perturbation expansion to second order--see Section 7.5.) However, both the proton and

the electron are spin one-half particles. According to Section 6.4,

when two spin one-half particles are combined (in the absence of orbital

angular momentum) the resulting state has either spin 1 or spin 0.

In fact, there are three spin 1 states, known as triplet states, and a single

spin 0 state, known as the singlet state. For all states,

the eigenvalues of

. (The use of simultaneous eigenstates of the perturbing and main Hamiltonian

avoids the possibility of singular terms arising in the perturbation expansion to second order--see Section 7.5.) However, both the proton and

the electron are spin one-half particles. According to Section 6.4,

when two spin one-half particles are combined (in the absence of orbital

angular momentum) the resulting state has either spin 1 or spin 0.

In fact, there are three spin 1 states, known as triplet states, and a single

spin 0 state, known as the singlet state. For all states,

the eigenvalues of  and

and  are

are

.

The eigenvalue of

.

The eigenvalue of  is 0 for the singlet state, and

is 0 for the singlet state, and

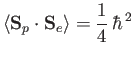

for the triplet states. Hence,

for the triplet states. Hence,

|

(7.164) |

for the singlet state, and

|

(7.165) |

for the triplet states.

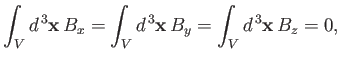

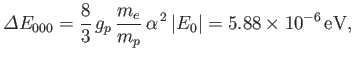

It follows, from the previous analysis, that proton-electron spin-spin coupling breaks

the degeneracy of the two

states of the hydrogen atom, lifting the

energy of the triplet configuration, and lowering that of the singlet.

This splitting is known as hyperfine structure.

The net energy difference between the singlet and the triplet states

is

states of the hydrogen atom, lifting the

energy of the triplet configuration, and lowering that of the singlet.

This splitting is known as hyperfine structure.

The net energy difference between the singlet and the triplet states

is

|

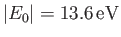

(7.166) |

where

is the (magnitude of the) ground-state energy, and

is the (magnitude of the) ground-state energy, and

the

fine structure constant.

Note that the hyperfine energy-shift is much smaller, by a factor

the

fine structure constant.

Note that the hyperfine energy-shift is much smaller, by a factor  , than

a typical fine structure energy-shift. (See Exercise 14.)

If we convert the previous energy into a wavelength (using

, than

a typical fine structure energy-shift. (See Exercise 14.)

If we convert the previous energy into a wavelength (using

) then we obtain

) then we obtain

|

(7.167) |

This is the wavelength of the radiation emitted by a hydrogen atom

that is collisionally excited from the singlet to the triplet

state, and then decays back to the lower energy singlet state.

The 21cm line is famous in radio astronomy because it was used to

map out the spiral structure of our galaxy in the 1950's [114].

Next: Exercises

Up: Time-Independent Perturbation Theory

Previous: Zeeman Effect

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-22

![]() located at the

origin is [49]

located at the

origin is [49]

![$\displaystyle =\frac{\mu_0}{4\pi} \oint d{\mit\Omega}\,{\bf e}_r\times ({\bf M}...

...u_0}{4\pi} \oint d{\mit\Omega} \,[{\bf M} - ({\bf M}\cdot{\bf e}_r)\,{\bf e}_r]$](img2086.png)

![$\displaystyle {\bf B} =\frac{\mu_0}{4\pi}\left[ \frac{3\,({\bf M}\cdot{\bf e}_r...

...-{\bf M}}{r^{\,3}}\right] + \frac{2\,\mu_0}{3}\,\delta^{\,3}({\bf x})\,{\bf M}.$](img2099.png)

![]()

![]() , generates a

magnetic field of the form

, generates a

magnetic field of the form

![$\displaystyle {\bf B} = \frac{\mu_0}{4\pi\,r^{\,3}}\,\left[3\,(\mbox{\boldmath$...

...p\right] + \frac{2\,\mu_0}{3}\,\delta^{\,3}({\bf x})\,\mbox{\boldmath$\mu$}_p\,$](img2104.png)

![]() states of the hydrogen atom, lifting the

energy of the triplet configuration, and lowering that of the singlet.

This splitting is known as hyperfine structure.

The net energy difference between the singlet and the triplet states

is

states of the hydrogen atom, lifting the

energy of the triplet configuration, and lowering that of the singlet.

This splitting is known as hyperfine structure.

The net energy difference between the singlet and the triplet states

is