Next: Clebsch-Gordon Coefficients

Up: Addition of Angular Momentum

Previous: Introduction

Consider the most general case. Suppose

that we have two sets of angular momentum operators,  and

and  .

By definition, these operators are Hermitian, and obey the fundamental commutation

relations

.

By definition, these operators are Hermitian, and obey the fundamental commutation

relations

Let us assume that the two groups of operators correspond to different degrees

of freedom of the system, so that

![$\displaystyle [J_{1\,i}, J_{2\,j}] = 0,$](img1618.png) |

(6.3) |

where  stand for either

stand for either  ,

,  , or

, or  . (See Section 2.2.)

For instance,

. (See Section 2.2.)

For instance,  could be an orbital angular momentum operator, and

could be an orbital angular momentum operator, and  a spin angular momentum operator. Alternatively,

a spin angular momentum operator. Alternatively,  and

and  could

be the orbital angular momentum operators

of two different particles in a multi-particle

system. We know, from the general

properties of angular momentum outlined in the previous two chapters, that the eigenvalues of

could

be the orbital angular momentum operators

of two different particles in a multi-particle

system. We know, from the general

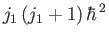

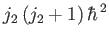

properties of angular momentum outlined in the previous two chapters, that the eigenvalues of  and

and  can be

written

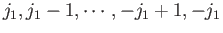

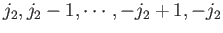

can be

written

and

and

, respectively, where

, respectively, where

and

and  are either integers, or half-integers. We also know that the

eigenvalues of

are either integers, or half-integers. We also know that the

eigenvalues of  and

and  take the form

take the form

and

and

, respectively, where

, respectively, where  and

and  are numbers

lying in the ranges

are numbers

lying in the ranges

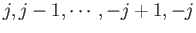

and

and

, respectively.

, respectively.

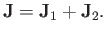

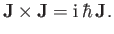

Let us define the total angular momentum operator

|

(6.4) |

Now,  is an Hermitian operator, because it is the sum of Hermitian operators.

Moreover, according to Equation (4.14),

is an Hermitian operator, because it is the sum of Hermitian operators.

Moreover, according to Equation (4.14),  satisfies the fundamental commutation

relation

satisfies the fundamental commutation

relation

|

(6.5) |

Thus,  possesses all of the expected properties of an

angular momentum operator. It follows that the eigenvalue of

possesses all of the expected properties of an

angular momentum operator. It follows that the eigenvalue of  can be

written

can be

written

, where

, where  is an integer, or a half-integer. Moreover, the eigenvalue

of

is an integer, or a half-integer. Moreover, the eigenvalue

of  takes the form

takes the form  , where

, where  lies in the range

lies in the range

. At this stage, however, we do not know the relationship between the quantum

numbers of the total angular momentum,

. At this stage, however, we do not know the relationship between the quantum

numbers of the total angular momentum,  and

and  , and those of the

individual angular momenta,

, and those of the

individual angular momenta,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  .

.

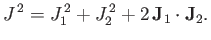

Now,

|

(6.6) |

Furthermore, we know that

and also that all of the  ,

,  operators commute with the

operators commute with the  ,

,  operators.

It follows from Equation (6.6) that

operators.

It follows from Equation (6.6) that

![$\displaystyle [J^{\,2}, J_1^{\,2}] = [J^{\,2}, J_2^{\,2}] = 0.$](img1645.png) |

(6.9) |

This implies that the quantum numbers  ,

,  , and

, and  can all be measured

simultaneously. In other words, it is possible to determine the magnitude of the total

angular momentum together with the magnitudes of the component

angular momenta. However, it is apparent from Equations (6.1), (6.2), and (6.6)

that

can all be measured

simultaneously. In other words, it is possible to determine the magnitude of the total

angular momentum together with the magnitudes of the component

angular momenta. However, it is apparent from Equations (6.1), (6.2), and (6.6)

that

This suggests that it is not possible to measure the quantum numbers  and

and  simultaneously with the quantum number

simultaneously with the quantum number  . Thus, we cannot determine

the projections of the individual angular momenta along the

. Thus, we cannot determine

the projections of the individual angular momenta along the  -axis together with the magnitude of the total angular momentum.

-axis together with the magnitude of the total angular momentum.

It is clear, from the preceding discussion, that we can form two alternate groups

of mutually commuting operators. The first group

is

, and

, and

. The second group is

. The second group is

and

and  . These two

groups of operators are incompatible with one another. We can define simultaneous

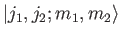

eigenkets of each operator group. The simultaneous eigenkets of

. These two

groups of operators are incompatible with one another. We can define simultaneous

eigenkets of each operator group. The simultaneous eigenkets of

, and

, and

are denoted

are denoted

, where

, where

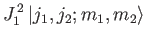

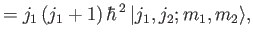

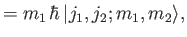

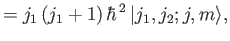

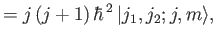

|

|

(6.12) |

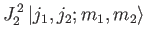

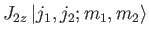

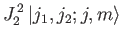

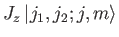

|

|

(6.13) |

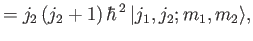

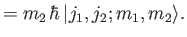

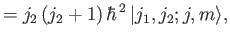

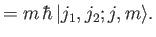

|

|

(6.14) |

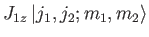

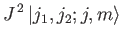

|

|

(6.15) |

The simultaneous eigenkets of

and

and  are denoted

are denoted

, where

, where

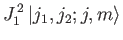

|

|

(6.16) |

|

|

(6.17) |

|

|

(6.18) |

|

|

(6.19) |

Each set of eigenkets are complete, mutually orthogonal (for eigenkets corresponding

to different sets of eigenvalues), and have unit norms. Because the operators

and

and  are common to both operator groups, we can assume

that the quantum numbers

are common to both operator groups, we can assume

that the quantum numbers  and

and  are known. In other words, we

can always determine

the magnitudes of the individual angular momenta. In addition, we can either

know the quantum numbers

are known. In other words, we

can always determine

the magnitudes of the individual angular momenta. In addition, we can either

know the quantum numbers  and

and  , or the quantum numbers

, or the quantum numbers  and

and

, but we cannot know both pairs of quantum numbers at the same time.

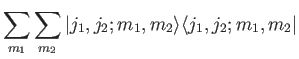

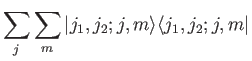

Finally, we can write a conventional completeness relation for both sets of

eigenkets:

, but we cannot know both pairs of quantum numbers at the same time.

Finally, we can write a conventional completeness relation for both sets of

eigenkets:

where the right-hand sides denote the identity operator in the ket space corresponding

to states of given  and

and  . The summation is over all allowed values

of

. The summation is over all allowed values

of  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  .

.

Next: Clebsch-Gordon Coefficients

Up: Addition of Angular Momentum

Previous: Introduction

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-22

![]() , and

, and

![]() . The second group is

. The second group is

![]() and

and ![]() . These two

groups of operators are incompatible with one another. We can define simultaneous

eigenkets of each operator group. The simultaneous eigenkets of

. These two

groups of operators are incompatible with one another. We can define simultaneous

eigenkets of each operator group. The simultaneous eigenkets of

![]() , and

, and

![]() are denoted

are denoted

![]() , where

, where