Next: Exercises

Up: Identical Particles

Previous: Variational Principle

Hydrogen Molecule Ion

The hydrogen molecule ion consists of an electron orbiting about

two protons, and is the simplest imaginable molecule. Let us

investigate whether this molecule possesses a bound state: that is, whether it possesses a ground-state whose energy is less than that of

a ground-state hydrogen atom plus a free proton.

In fact, according

to the variational principle (see the previous section), we can prove that the  ion possesses a bound state if we can find any

trial wavefunction for which the total Hamiltonian of the system has an expectation value that is less than that of a

ground-state hydrogen atom plus a free proton.

ion possesses a bound state if we can find any

trial wavefunction for which the total Hamiltonian of the system has an expectation value that is less than that of a

ground-state hydrogen atom plus a free proton.

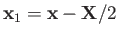

Suppose that the first and second protons lie at

and

and

, respectively. Let

, respectively. Let  be the position vector

of the electron. The position vectors of the electron relative to the first and second protons are thus

be the position vector

of the electron. The position vectors of the electron relative to the first and second protons are thus

and

and

, respectively.

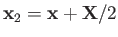

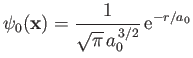

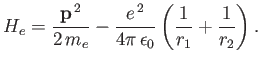

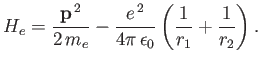

The Hamiltonian of the system is written

, respectively.

The Hamiltonian of the system is written

|

(9.97) |

where  is the electron momentum,

is the electron momentum,

,

,

, and

, and

.

Here, we are treating the

protons as essentially stationary, which is a reasonable approximation because the electron's

motion is much more rapid than that of the protons. Of course, this is the case because the electron mass is very much less than the proton mass.

Incidentally, the neglect of nuclear motion when calculating the electronic structure of a molecule is known as the Born-Oppenheimer approximation [13].

.

Here, we are treating the

protons as essentially stationary, which is a reasonable approximation because the electron's

motion is much more rapid than that of the protons. Of course, this is the case because the electron mass is very much less than the proton mass.

Incidentally, the neglect of nuclear motion when calculating the electronic structure of a molecule is known as the Born-Oppenheimer approximation [13].

The Hamiltonian (9.98) is manifestly invariant under the transformation

, which simply

swaps the positions of the two identical protons.

This transformation is equivalent to

, which simply

swaps the positions of the two identical protons.

This transformation is equivalent to

. If

. If  is the operator that swaps the proton positions then it is clear that

is the operator that swaps the proton positions then it is clear that

. (See Exercise 1.) Hence, the eigenvalues of

. (See Exercise 1.) Hence, the eigenvalues of  are

are

. Furthermore, the fact that the Hamiltonian is invariant under exchange of proton positions implies that

. Furthermore, the fact that the Hamiltonian is invariant under exchange of proton positions implies that

![$ [P_{12}, H]=0$](img3209.png) . (See Section 9.2.) Thus, the eigenkets of the Hamiltonian are simultaneous eigenkets of

. (See Section 9.2.) Thus, the eigenkets of the Hamiltonian are simultaneous eigenkets of  . Now, it

is easily shown that the eigenkets of

. Now, it

is easily shown that the eigenkets of  corresponding to the eigenvalues

corresponding to the eigenvalues  are, respectively, even and odd under

the transformation

are, respectively, even and odd under

the transformation

. (See Exercise 2.)

It follows that the ground-state wavefunction of the

. (See Exercise 2.)

It follows that the ground-state wavefunction of the  ion has the general form

ion has the general form

![$\displaystyle \psi_\pm({\bf x}) = A\left[\psi_0({\bf x}_1) \pm \psi_0({\bf x}_2)\right],$](img3210.png) |

(9.98) |

where  is a complex number.

is a complex number.

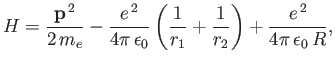

Let us adopt

|

(9.99) |

as our trial single-proton wavefunction, where

.

Here,

.

Here,

is a properly normalized hydrogen ground-state wavefunction, and

is a properly normalized hydrogen ground-state wavefunction, and  is the Bohr radius.

Thus, our trial molecular wavefunction, which is specified in Equations (9.99) and (9.100), is simply a linear combination of hydrogen ground-state

wavefunctions centered on each proton [18].

is the Bohr radius.

Thus, our trial molecular wavefunction, which is specified in Equations (9.99) and (9.100), is simply a linear combination of hydrogen ground-state

wavefunctions centered on each proton [18].

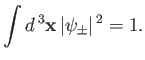

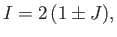

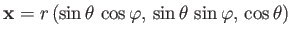

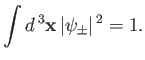

Our first task is to normalize the trial wavefunction. We require that

|

(9.100) |

Hence, from Equation (9.99),

, where

, where

![$\displaystyle I = \int d^{\,3}{\bf x}\left[\vert\psi_0({\bf x}_1)\vert^{\,2} + ...

...psi_0({\bf x}_2)\vert^{\,2} \pm 2\,\psi_0({\bf x}_1)\,\psi_0({\bf x}_2)\right].$](img3215.png) |

(9.101) |

It follows that

|

(9.102) |

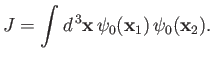

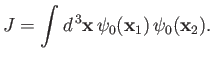

where

|

(9.103) |

Without loss of generality, we can perform the previous integral using a modified coordinate system in which the

first proton lies at the origin, and the second at

.

Let

.

Let

be the position vector of the electron.

It follows that

be the position vector of the electron.

It follows that  and

and

.

Hence,

.

Hence,

where  and

and  . Here, we have already performed the trivial

. Here, we have already performed the trivial  integral.

Let

integral.

Let

. It follows that

. It follows that

, giving

, giving

Thus,

which evaluates to

|

(9.107) |

(See Exercise 20.)

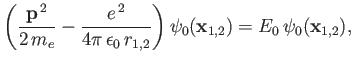

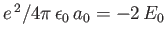

Now, the Hamiltonian of the electron is written

|

(9.108) |

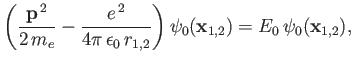

Note, however, that

|

(9.109) |

where  is the hydrogen ground-state energy,

because the

is the hydrogen ground-state energy,

because the

are hydrogen ground-state wavefunctions.

It follows that

are hydrogen ground-state wavefunctions.

It follows that

Hence,

|

(9.111) |

where

Here, use has been made of the fact that

, as well as the fact that

the Hamiltonian is invariant under the transformation

, as well as the fact that

the Hamiltonian is invariant under the transformation

.

.

Now,

|

(9.114) |

where  and

and  ,

which reduces to

,

which reduces to

|

(9.115) |

giving

![$\displaystyle D = \frac{1}{y} \left[ 1-(1+y)\,{\rm e}^{\,-2\,y}\right].$](img3246.png) |

(9.116) |

(See Exercise 21.)

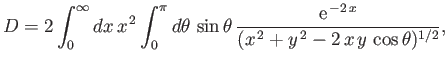

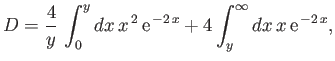

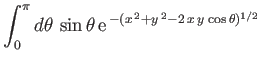

Furthermore,

![$\displaystyle E = 2\int_0^\infty dx\,x\int_0^\pi d\theta\,\sin\theta\,\exp\left[-x-(x^{\,2}+y^{\,2}-2\,x\,y\,\cos\theta)^{1/2}\right],$](img3247.png) |

(9.117) |

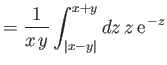

which reduces to

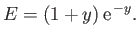

yielding

|

(9.119) |

(See Exercise 22.)

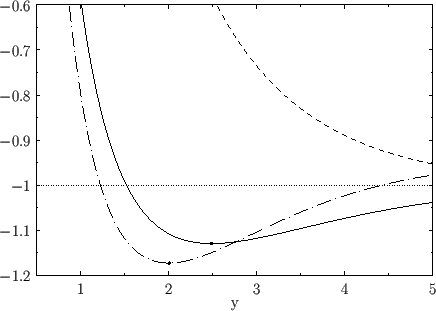

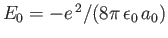

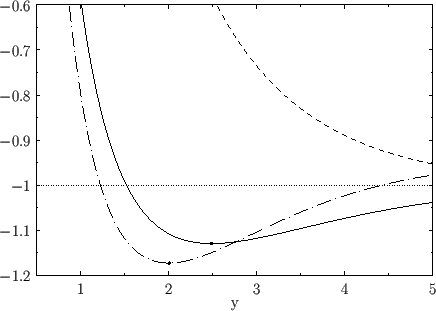

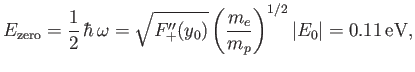

Figure:

The functions  (solid curve) and

(solid curve) and  (short-dashed curve), where

(short-dashed curve), where  . The

long-dash-dotted curve shows the improved

. The

long-dash-dotted curve shows the improved  curve obtained from Exercise 23. The dots

indicate the minimum values of

curve obtained from Exercise 23. The dots

indicate the minimum values of  .

.

|

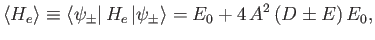

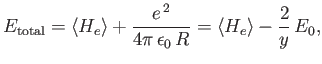

Our final expression for the expectation value of the electron Hamiltonian is

![$\displaystyle \langle H_e\rangle = \left[1+ 2\,\frac{(D\pm E)}{(1\pm J)}\right] E_0,$](img3252.png) |

(9.120) |

where  ,

,  , and

, and  are specified as functions of

are specified as functions of  in

Equations (9.108), (9.117), and (9.120), respectively.

In order

to obtain the total energy of the molecule, we must add the

potential energy of the two protons to this expectation value. Thus,

in

Equations (9.108), (9.117), and (9.120), respectively.

In order

to obtain the total energy of the molecule, we must add the

potential energy of the two protons to this expectation value. Thus,

|

(9.121) |

because

.

Hence, we can write

.

Hence, we can write

|

(9.122) |

where

![$\displaystyle F_\pm(y) = -1 + \frac{2}{y}\left[\frac{(1+y)\,{\rm e}^{\,-2\,y}\pm(1-2\,y^{\,2}/3) \,{\rm e}^{\,-y}}{1\pm (1+y+y^{\,2}/3)\,{\rm e}^{\,-y}}\right].$](img3255.png) |

(9.123) |

The functions  and

and  are plotted in Fig. 9.1.

Recall that, in order for the

are plotted in Fig. 9.1.

Recall that, in order for the  ion possess a bound state, it must have a lower

energy than a hydrogen atom and a free proton. In other words,

ion possess a bound state, it must have a lower

energy than a hydrogen atom and a free proton. In other words,

. It follows, from Equation (9.123), that a bound state

corresponds to

. It follows, from Equation (9.123), that a bound state

corresponds to

. It is clear, from the figure, that the even trial wavefunction,

. It is clear, from the figure, that the even trial wavefunction,  ,

possesses a bound state, whereas the odd trial wavefunction,

,

possesses a bound state, whereas the odd trial wavefunction,  ,

does not. [See Equation (9.99).] This is hardly surprising, because the

even wavefunction maximizes the electron probability density between

the two protons, thereby reducing their mutual electrostatic repulsion. On the other hand, the odd

wavefunction does exactly the opposite. The binding energy of the

,

does not. [See Equation (9.99).] This is hardly surprising, because the

even wavefunction maximizes the electron probability density between

the two protons, thereby reducing their mutual electrostatic repulsion. On the other hand, the odd

wavefunction does exactly the opposite. The binding energy of the

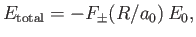

ion is defined as minus the difference between its energy and that of a

hydrogen atom plus a free proton: that is,

ion is defined as minus the difference between its energy and that of a

hydrogen atom plus a free proton: that is,

|

(9.124) |

According to the variational principle, the binding energy is greater than, or

equal to, the maximum binding energy that can be inferred from Figure 9.1. (A maximum in the binding energy

corresponds to a minimum of  .)

This maximum occurs when

.)

This maximum occurs when

and

and

.

Thus, our estimates for the equilibrium separation between the two

protons, and the binding energy of the molecule,

are

.

Thus, our estimates for the equilibrium separation between the two

protons, and the binding energy of the molecule,

are

and

and

eV, respectively. The experimentally

determined values are

eV, respectively. The experimentally

determined values are

m, and

m, and

eV, respectively [53]. Clearly, the previous estimates are not particularly accurate. However,

our calculation does establish, beyond any doubt, the existence of

a bound state of the

eV, respectively [53]. Clearly, the previous estimates are not particularly accurate. However,

our calculation does establish, beyond any doubt, the existence of

a bound state of the  ion, which is all that we set out to achieve. (See Exercise 23 for a somewhat

improved calculation.)

ion, which is all that we set out to achieve. (See Exercise 23 for a somewhat

improved calculation.)

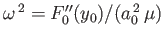

We can think of the two constituent protons of the hydrogen molecule ion, whose separation is  , as moving in an electric potential

, as moving in an electric potential

due to the combination of their electrostatic repulsion and the binding action of the consistent electron.

Moreover, close to the equilibrium separation,

due to the combination of their electrostatic repulsion and the binding action of the consistent electron.

Moreover, close to the equilibrium separation,  , we have

, we have

![$ V(R)\simeq V(R_0) + \left[(1/2)\,F_0''(y_0)/a_0^{\,2}\right]x^{\,2}+ {\cal O}(x^{\,3})$](img3268.png) , where

, where  .

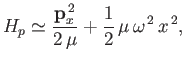

Thus, in the center of mass frame [50], the protons' Hamiltonian takes the form

.

Thus, in the center of mass frame [50], the protons' Hamiltonian takes the form

|

(9.125) |

where  is the momentum conjugate to

is the momentum conjugate to  ,

,

the reduced mass [50],

the reduced mass [50],  the proton mass,

the proton mass,

, and we have neglected an unimportant constant term. Here,

, and we have neglected an unimportant constant term. Here,  denotes

denotes  . It can be seen, by comparison with Exercise 3,

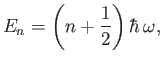

that the previous Hamiltonian is identical to that of a harmonic oscillator. Thus, the allowed radial oscillation energies of the molecule are

. It can be seen, by comparison with Exercise 3,

that the previous Hamiltonian is identical to that of a harmonic oscillator. Thus, the allowed radial oscillation energies of the molecule are

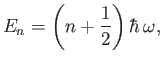

|

(9.126) |

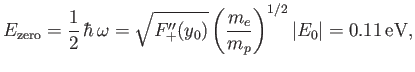

where  is a non-negative integer. In particular, there is a non-zero lowest oscillation energy--the so-called zero-point energy [40],

is a non-negative integer. In particular, there is a non-zero lowest oscillation energy--the so-called zero-point energy [40],

|

(9.127) |

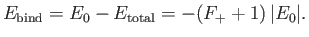

that must be subtracted from the previously determined electric binding energy of

to give the true binding energy.

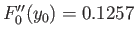

In calculating,

to give the true binding energy.

In calculating,

we have made use of the numerically determined value

we have made use of the numerically determined value

[derived from Equation (9.124.)]

[derived from Equation (9.124.)]

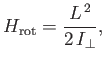

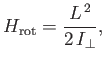

Of course, the hydrogen molecule ion can rotate, as well as vibrate. According to Exercise 7, the rotational

component of the molecular Hamiltonian can be written

|

(9.128) |

where  is the angular momentum of rotation, and

is the angular momentum of rotation, and

is the molecular moment of inertia [about a perpendicular (to

the line joining the two protons) axis passing through the center of mass].

In calculating the moment of inertia, we have neglected the electron mass, and have treated the protons as point particles. The analysis of Exercise 7

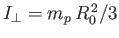

reveals that the rotational energy levels are

is the molecular moment of inertia [about a perpendicular (to

the line joining the two protons) axis passing through the center of mass].

In calculating the moment of inertia, we have neglected the electron mass, and have treated the protons as point particles. The analysis of Exercise 7

reveals that the rotational energy levels are

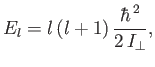

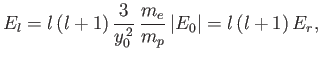

|

(9.129) |

where the eigenvalues of  are

are

, and

, and  is a non-negative integer. It follows that

is a non-negative integer. It follows that

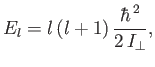

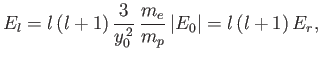

|

(9.130) |

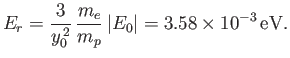

where

|

(9.131) |

Note that our estimate for the electric binding energy of the hydrogen molecule ion,

, is significantly

greater than our estimate for the zero-point oscillation energy,

, is significantly

greater than our estimate for the zero-point oscillation energy,

, which, in turn, is very much greater

than a typical rotational energy,

, which, in turn, is very much greater

than a typical rotational energy,

. This separation in energy scales lies at the heart of

the previously mentioned Born-Oppenheimer approximation [13], according to which the electric, vibrational, and rotational energy levels of molecules

can all be calculated independently of one another.

. This separation in energy scales lies at the heart of

the previously mentioned Born-Oppenheimer approximation [13], according to which the electric, vibrational, and rotational energy levels of molecules

can all be calculated independently of one another.

Next: Exercises

Up: Identical Particles

Previous: Variational Principle

Richard Fitzpatrick

2016-01-22

![]() and

and

![]() , respectively. Let

, respectively. Let ![]() be the position vector

of the electron. The position vectors of the electron relative to the first and second protons are thus

be the position vector

of the electron. The position vectors of the electron relative to the first and second protons are thus

![]() and

and

![]() , respectively.

The Hamiltonian of the system is written

, respectively.

The Hamiltonian of the system is written

![]() , which simply

swaps the positions of the two identical protons.

This transformation is equivalent to

, which simply

swaps the positions of the two identical protons.

This transformation is equivalent to

![]() . If

. If ![]() is the operator that swaps the proton positions then it is clear that

is the operator that swaps the proton positions then it is clear that

![]() . (See Exercise 1.) Hence, the eigenvalues of

. (See Exercise 1.) Hence, the eigenvalues of ![]() are

are

![]() . Furthermore, the fact that the Hamiltonian is invariant under exchange of proton positions implies that

. Furthermore, the fact that the Hamiltonian is invariant under exchange of proton positions implies that

![]() . (See Section 9.2.) Thus, the eigenkets of the Hamiltonian are simultaneous eigenkets of

. (See Section 9.2.) Thus, the eigenkets of the Hamiltonian are simultaneous eigenkets of ![]() . Now, it

is easily shown that the eigenkets of

. Now, it

is easily shown that the eigenkets of ![]() corresponding to the eigenvalues

corresponding to the eigenvalues ![]() are, respectively, even and odd under

the transformation

are, respectively, even and odd under

the transformation

![]() . (See Exercise 2.)

It follows that the ground-state wavefunction of the

. (See Exercise 2.)

It follows that the ground-state wavefunction of the ![]() ion has the general form

ion has the general form

![$\displaystyle I = \int d^{\,3}{\bf x}\left[\vert\psi_0({\bf x}_1)\vert^{\,2} + ...

...psi_0({\bf x}_2)\vert^{\,2} \pm 2\,\psi_0({\bf x}_1)\,\psi_0({\bf x}_2)\right].$](img3215.png)

![]() .

Let

.

Let

![]() be the position vector of the electron.

It follows that

be the position vector of the electron.

It follows that ![]() and

and

![]() .

Hence,

.

Hence,

![$\displaystyle = - \frac{1}{x\,y}\left[{\rm e}^{\,-(x+y)}\,(1+x+y) - {\rm e}^{\,-\vert x-y\vert}\,(1+\vert x-y\vert)\right].$](img3229.png)

![$\displaystyle =A\left[\frac{{\bf p}^{\,2}}{2\,m_e} - \frac{e^{\,2}}{4\pi\,\epsi...

...frac{1}{r_2}\right)\right] \left[\psi_0({\bf x}_1) \pm \psi_0({\bf x}_2)\right]$](img3237.png)

![$\displaystyle = E_0\,\psi_\pm - A\,\left(\frac{e^{\,2}}{4\pi\,\epsilon_0}\right)\left[ \frac{\psi_0({\bf x}_1)}{r_2}\pm \frac{\psi_0({\bf x}_2)}{r_1}\right].$](img3238.png)

![$\displaystyle \langle H_e\rangle = \left[1+ 2\,\frac{(D\pm E)}{(1\pm J)}\right] E_0,$](img3252.png)

![]() and

and ![]() are plotted in Fig. 9.1.

Recall that, in order for the

are plotted in Fig. 9.1.

Recall that, in order for the ![]() ion possess a bound state, it must have a lower

energy than a hydrogen atom and a free proton. In other words,

ion possess a bound state, it must have a lower

energy than a hydrogen atom and a free proton. In other words,

![]() . It follows, from Equation (9.123), that a bound state

corresponds to

. It follows, from Equation (9.123), that a bound state

corresponds to

![]() . It is clear, from the figure, that the even trial wavefunction,

. It is clear, from the figure, that the even trial wavefunction, ![]() ,

possesses a bound state, whereas the odd trial wavefunction,

,

possesses a bound state, whereas the odd trial wavefunction, ![]() ,

does not. [See Equation (9.99).] This is hardly surprising, because the

even wavefunction maximizes the electron probability density between

the two protons, thereby reducing their mutual electrostatic repulsion. On the other hand, the odd

wavefunction does exactly the opposite. The binding energy of the

,

does not. [See Equation (9.99).] This is hardly surprising, because the

even wavefunction maximizes the electron probability density between

the two protons, thereby reducing their mutual electrostatic repulsion. On the other hand, the odd

wavefunction does exactly the opposite. The binding energy of the

![]() ion is defined as minus the difference between its energy and that of a

hydrogen atom plus a free proton: that is,

ion is defined as minus the difference between its energy and that of a

hydrogen atom plus a free proton: that is,

![]() , as moving in an electric potential

, as moving in an electric potential

![]() due to the combination of their electrostatic repulsion and the binding action of the consistent electron.

Moreover, close to the equilibrium separation,

due to the combination of their electrostatic repulsion and the binding action of the consistent electron.

Moreover, close to the equilibrium separation, ![]() , we have

, we have

![]() , where

, where ![]() .

Thus, in the center of mass frame [50], the protons' Hamiltonian takes the form

.

Thus, in the center of mass frame [50], the protons' Hamiltonian takes the form

![]() , is significantly

greater than our estimate for the zero-point oscillation energy,

, is significantly

greater than our estimate for the zero-point oscillation energy,

![]() , which, in turn, is very much greater

than a typical rotational energy,

, which, in turn, is very much greater

than a typical rotational energy,

![]() . This separation in energy scales lies at the heart of

the previously mentioned Born-Oppenheimer approximation [13], according to which the electric, vibrational, and rotational energy levels of molecules

can all be calculated independently of one another.

. This separation in energy scales lies at the heart of

the previously mentioned Born-Oppenheimer approximation [13], according to which the electric, vibrational, and rotational energy levels of molecules

can all be calculated independently of one another.