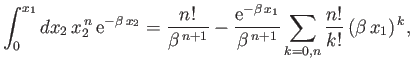

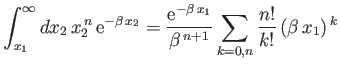

Demonstrate that

and

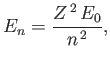

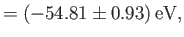

- Show that the energy levels are

where is the ground-state energy of a conventional hydrogen atom.

is the ground-state energy of a conventional hydrogen atom.

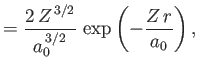

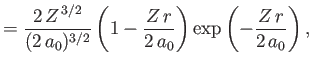

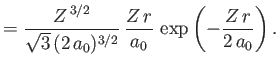

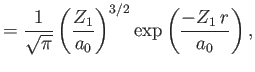

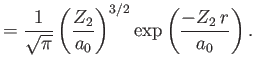

- Demonstrate that the first few properly normalized radial wavefunctions,

, take the form:

, take the form:

where is the Bohr radius.

is the Bohr radius.

and

Here,

where

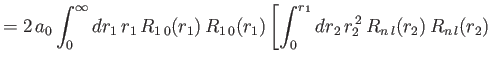

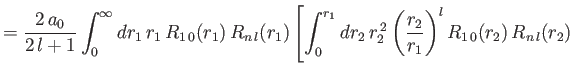

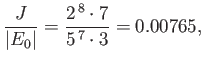

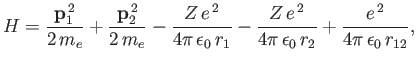

- Demonstrate that the expressions for the direct and exchange integrals given

in Section 9.6 reduce to

![$\displaystyle \phantom{=}\left.+\int_{r_1}^\infty dr_2\,r_1\,r_2\,R_{n\,l}(r_2)\,R_{n\,l}(r_2)\right],$](img3309.png)

and

![$\displaystyle \phantom{=}\left.+\int_{r_1}^\infty dr_2\,r_1\,r_2\left(\frac{r_1}{r_2}\right)^l R_{1\,0}(r_2)\,R_{n\,l}(r_2)\right],$](img3311.png)

respectively, where is a hydrogen radial wavefunction calculated with a nuclear charge

is a hydrogen radial wavefunction calculated with a nuclear charge  .

.

- Suppose that the excited electron is in the

,

,  ,

,  state (i.e., the

state (i.e., the  state). Show that

state). Show that

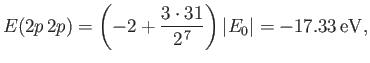

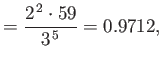

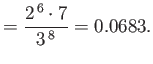

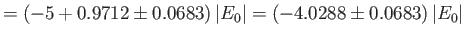

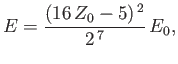

Hence, deduce that the energies of the states of orthohelium and parahelium are

states of orthohelium and parahelium are

where the upper sign corresponds to parahelium.

where the upper sign corresponds to parahelium [77]. It can be seen that the calculation in the previous exercise has considerably overestimated the size of the exchange integral. The main reason for this is that we neglected to take into account the fact that the

which yields

Note that this estimate is much closer to the experimental value (

where

and

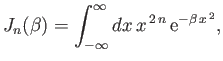

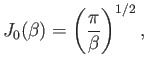

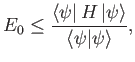

Suppose that

where

where

|

||

|

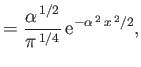

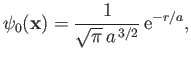

Verify that these wavefunctions are properly normalized. Use the variational principle, combined with the plausible trial wavefunctions

|

||

|

The exact numerical factors that should appear in the previous two equations are

where

|

|

|

||||

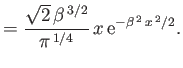

Obviously, we need to perform a more accurate calculation for the case of a negative hydrogen ion. Following Chandrasekhar [21], let us adopt the following trial wavefunction:

![$\displaystyle \phi({\bf x}_1,{\bf x}_2)=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[\psi_1({\bf x}_1)\,\psi_2({\bf x}_2)+\epsilon\,\psi_2({\bf x}_1)\,\psi_1({\bf x}_2)\right],

$](img3381.png)

where

|

||

|

Here,

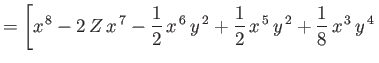

show that the expectation value of

|

||

![$\displaystyle \phantom{=}\left.\left.-\epsilon\left(2\,Z-\frac{5}{8}\right)x\,y...

...c{1}{2}\,\epsilon\,y^{\,8}\right]\right/\left(x^{\,6}+\epsilon\,y^{\,6}\right),$](img3389.png) |

where

The previous table shows the numerically determined values of ![]() and

and ![]() that minimize

that minimize

![]() for various choices of

for various choices of ![]() and

and ![]() . The table also shows the estimate for the ground-state

energy (

. The table also shows the estimate for the ground-state

energy (![]() ), as well as the corresponding experimentally measured ground-state energy (

), as well as the corresponding experimentally measured ground-state energy (

![]() ) [63,66]. It can

be seen that our new estimate for the ground-state energy of the negative hydrogen ion is now less than the

ground-state energy of a neutral hydrogen atom, which demonstrates that the negative hydrogen ion has

a positive (albeit, small) binding energy. Incidentally, the case

) [63,66]. It can

be seen that our new estimate for the ground-state energy of the negative hydrogen ion is now less than the

ground-state energy of a neutral hydrogen atom, which demonstrates that the negative hydrogen ion has

a positive (albeit, small) binding energy. Incidentally, the case ![]() ,

,

![]() yields a good estimate for the

energy of the lowest-energy spin-triplet state of a helium atom (i.e., the

yields a good estimate for the

energy of the lowest-energy spin-triplet state of a helium atom (i.e., the ![]() spin-triplet state).

spin-triplet state).

where

where

![$\displaystyle F_+(y)= -Z^{\,2} + \frac{2\,Z}{y}\left[

\frac{(1+y)\,{\rm e}^{-2\...

...+ (Z-1)\,y\,(1+[1+y]\,{\rm e}^{-y})}

{1+(1+y+y^{\,2}/3)\,{\rm e}^{-y}}\right].

$](img3399.png)

It can be shown, numerically, that the previous function attains its minimum value,

![]() , when

, when

![]() and

and ![]() . This leads to predictions for the equilibrium separation between the two

protons, and the binding energy of the molecule, of

. This leads to predictions for the equilibrium separation between the two

protons, and the binding energy of the molecule, of

![]() and

and

![]() , respectively. (See Figure 9.1.) These values are far closer to the

experimentally determined values,

, respectively. (See Figure 9.1.) These values are far closer to the

experimentally determined values,

![]() and

and

![]() [53], than

those derived in Section 9.8.

[53], than

those derived in Section 9.8.