Next: Anomalous Dispersion and Resonant

Up: Wave Propagation in Uniform

Previous: Introduction

Consider an electromagnetic wave propagating

through a transparent, isotropic, dielectric medium.

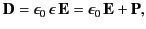

The electric displacement inside the medium is given by

|

(776) |

where  is the electric

polarization. Because electrons are much lighter than

ions (or atomic nuclei),

we would expect the former to displace further than the latter under

the influence of an electric field. Thus, to a first

approximation, the polarization,

is the electric

polarization. Because electrons are much lighter than

ions (or atomic nuclei),

we would expect the former to displace further than the latter under

the influence of an electric field. Thus, to a first

approximation, the polarization,  , is determined by the electron

response to the wave. Suppose that the electrons displace an average distance

, is determined by the electron

response to the wave. Suppose that the electrons displace an average distance

from their rest positions in the presence of the wave. It follows

that

from their rest positions in the presence of the wave. It follows

that

|

(777) |

where  is the number density of electrons, and

is the number density of electrons, and  the electron charge.

the electron charge.

Let us assume that the electrons are bound ``quasi-elastically'' to

their rest positions, so that they seek to return to these positions

when displaced from them by an electric field. It follows that  satisfies a differential equation of the form

satisfies a differential equation of the form

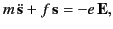

|

(778) |

where  is the electron mass,

is the electron mass,

is the restoring force,

and

is the restoring force,

and  denotes a partial derivative with respect to time.

The previous equation can also be written

denotes a partial derivative with respect to time.

The previous equation can also be written

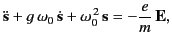

|

(779) |

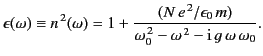

where

|

(780) |

is the characteristic oscillation

frequency of the electrons. In almost all dielectric

media, this frequency lies in the far ultraviolet region of the

electromagnetic spectrum. Note that we have added a phenomenological

damping term,

, to Equation (780), in order to take into account the

fact that an electron excited by an impulsive electric field does not

oscillate for ever. In fact, electrons in dielectric media

act like high-Q oscillators, which is another way of

saying that the dimensionless damping constant,

, to Equation (780), in order to take into account the

fact that an electron excited by an impulsive electric field does not

oscillate for ever. In fact, electrons in dielectric media

act like high-Q oscillators, which is another way of

saying that the dimensionless damping constant,  , is typically much less than

unity. Thus, an electron in a dielectric medium ``rings'' for a long time after being excited by an electromagnetic

impulse.

, is typically much less than

unity. Thus, an electron in a dielectric medium ``rings'' for a long time after being excited by an electromagnetic

impulse.

Let us assume that the electrons oscillate in sympathy with the wave at the

wave frequency,  . It follows from Equation (780) that

. It follows from Equation (780) that

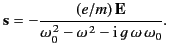

|

(781) |

Here, we have neglected the response of the electrons to the

magnetic component of the wave. It is easily demonstrated that this

is a good approximation provided the electrons do not oscillate with

relativistic velocities (i.e., provided the amplitude of

the wave is not too large--see Section 7.7).

Thus, Equation (778) yields

|

(782) |

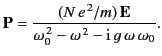

Because, by definition,

|

(783) |

it follows

that

|

(784) |

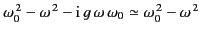

Thus, the index of refraction is indeed frequency dependent. Because  typically lies in the ultraviolet region of the spectrum (and

typically lies in the ultraviolet region of the spectrum (and

), it is clear that the denominator,

), it is clear that the denominator,

, is positive throughout the visible spectrum, and is

larger at the red than at the blue end of this spectrum. This implies that

blue light is refracted more strongly than red light. This state of affairs, in which higher frequency waves are refracted more strongly than

lower frequency waves, is termed normal

dispersion. Incidentally, an expression, like the previous one, that (effectively) specifies the

phase velocity of waves propagating through a dielectric medium, as a function of their frequency, is usually

called a dispersion relation.

, is positive throughout the visible spectrum, and is

larger at the red than at the blue end of this spectrum. This implies that

blue light is refracted more strongly than red light. This state of affairs, in which higher frequency waves are refracted more strongly than

lower frequency waves, is termed normal

dispersion. Incidentally, an expression, like the previous one, that (effectively) specifies the

phase velocity of waves propagating through a dielectric medium, as a function of their frequency, is usually

called a dispersion relation.

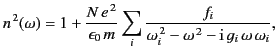

Let us now suppose that there are  molecules per unit volume,

with

molecules per unit volume,

with  electrons per molecule, and that, instead of a single oscillation

frequency for all electrons, there are

electrons per molecule, and that, instead of a single oscillation

frequency for all electrons, there are  electrons per molecule with

oscillation frequency

electrons per molecule with

oscillation frequency  and damping constant

and damping constant  . It is

easily demonstrated that Equation (785) generalizes to give

. It is

easily demonstrated that Equation (785) generalizes to give

|

(785) |

where the oscillator strengths,  , satisfy the sum rule,

, satisfy the sum rule,

|

(786) |

A more exact quantum mechanical treatment of the response of an atom,

or molecule, to a low amplitude electromagnetic wave also leads to a

dispersion relation

of the previous form, except that the quantities

,

,  , and

, and  can, in principle,

be calculated exactly. In practice, this is too difficult, except

in very simple cases.

can, in principle,

be calculated exactly. In practice, this is too difficult, except

in very simple cases.

Because the damping constants,  , are generally small compared to unity,

it follows from Equation (786) that

, are generally small compared to unity,

it follows from Equation (786) that  is a predominately real

quantity at most wave frequencies. The factor

is a predominately real

quantity at most wave frequencies. The factor

is positive for

is positive for

, and negative for

, and negative for

.

Thus, at low frequencies (i.e., below the smallest

.

Thus, at low frequencies (i.e., below the smallest  ) all of the terms

appearing in the sum on the right-hand side of (786) are positive, and

) all of the terms

appearing in the sum on the right-hand side of (786) are positive, and  is consequently

greater than unity. As

is consequently

greater than unity. As  is raised, such that

it exceeds successive

is raised, such that

it exceeds successive  values, more and more negative terms occur

in

the sum, until eventually the whole sum is negative, and

values, more and more negative terms occur

in

the sum, until eventually the whole sum is negative, and  is less than unity. Hence, at very high frequencies, electromagnetic

waves propagate through dielectric media with phase velocities that exceed

the velocity of light in a vacuum. For

is less than unity. Hence, at very high frequencies, electromagnetic

waves propagate through dielectric media with phase velocities that exceed

the velocity of light in a vacuum. For

,

Equation (786) predicts strong variation of the refractive index with

frequency. Let us examine this phenomenon more closely.

,

Equation (786) predicts strong variation of the refractive index with

frequency. Let us examine this phenomenon more closely.

Next: Anomalous Dispersion and Resonant

Up: Wave Propagation in Uniform

Previous: Introduction

Richard Fitzpatrick

2014-06-27

![]() satisfies a differential equation of the form

satisfies a differential equation of the form

![]() . It follows from Equation (780) that

. It follows from Equation (780) that

![]() molecules per unit volume,

with

molecules per unit volume,

with ![]() electrons per molecule, and that, instead of a single oscillation

frequency for all electrons, there are

electrons per molecule, and that, instead of a single oscillation

frequency for all electrons, there are ![]() electrons per molecule with

oscillation frequency

electrons per molecule with

oscillation frequency ![]() and damping constant

and damping constant ![]() . It is

easily demonstrated that Equation (785) generalizes to give

. It is

easily demonstrated that Equation (785) generalizes to give

![]() , are generally small compared to unity,

it follows from Equation (786) that

, are generally small compared to unity,

it follows from Equation (786) that ![]() is a predominately real

quantity at most wave frequencies. The factor

is a predominately real

quantity at most wave frequencies. The factor

![]() is positive for

is positive for

![]() , and negative for

, and negative for

![]() .

Thus, at low frequencies (i.e., below the smallest

.

Thus, at low frequencies (i.e., below the smallest ![]() ) all of the terms

appearing in the sum on the right-hand side of (786) are positive, and

) all of the terms

appearing in the sum on the right-hand side of (786) are positive, and ![]() is consequently

greater than unity. As

is consequently

greater than unity. As ![]() is raised, such that

it exceeds successive

is raised, such that

it exceeds successive ![]() values, more and more negative terms occur

in

the sum, until eventually the whole sum is negative, and

values, more and more negative terms occur

in

the sum, until eventually the whole sum is negative, and ![]() is less than unity. Hence, at very high frequencies, electromagnetic

waves propagate through dielectric media with phase velocities that exceed

the velocity of light in a vacuum. For

is less than unity. Hence, at very high frequencies, electromagnetic

waves propagate through dielectric media with phase velocities that exceed

the velocity of light in a vacuum. For

![]() ,

Equation (786) predicts strong variation of the refractive index with

frequency. Let us examine this phenomenon more closely.

,

Equation (786) predicts strong variation of the refractive index with

frequency. Let us examine this phenomenon more closely.