Next: Rayleigh Scattering

Up: Radiation and Scattering

Previous: Antenna Arrays

When an electromagnetic wave is incident on a charged particle, the

electric and magnetic components of the wave exert a Lorentz force

on the particle, setting it into motion. Because the wave is periodic

in time, so is the motion of the particle. Thus, the particle is accelerated

and, consequently, emits radiation. More exactly, energy is

absorbed from the incident wave by the particle,

and re-emitted as electromagnetic radiation. Such

a process is clearly equivalent to the scattering of the electromagnetic

wave by the particle.

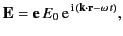

Consider a linearly polarized, monochromatic, plane wave incident on a

particle of charge  . The electric component of the wave can be

written

. The electric component of the wave can be

written

|

(1273) |

where  is the peak amplitude of the electric field,

is the peak amplitude of the electric field,  is

the polarization vector, and

is

the polarization vector, and  is the wave vector

(of course,

is the wave vector

(of course,

).

The particle is assumed to undergo small

amplitude oscillations about an equilibrium position that coincides with

the origin of the coordinate system. Furthermore,

the particle's velocity is assumed

to remain sub-relativistic, which enables us to neglect the magnetic

component of the Lorentz force. The equation of motion of

the charged particle is approximately

).

The particle is assumed to undergo small

amplitude oscillations about an equilibrium position that coincides with

the origin of the coordinate system. Furthermore,

the particle's velocity is assumed

to remain sub-relativistic, which enables us to neglect the magnetic

component of the Lorentz force. The equation of motion of

the charged particle is approximately

|

(1274) |

where  is the mass of the particle,

is the mass of the particle,  is its displacement from the origin, and

is its displacement from the origin, and  denotes

denotes

.

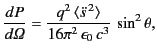

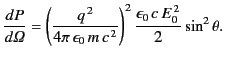

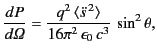

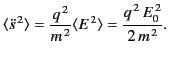

By analogy with Equation (1234), the time-averaged power radiated per unit solid

angle by an accelerating, non-relativistic, charged particle is given by

.

By analogy with Equation (1234), the time-averaged power radiated per unit solid

angle by an accelerating, non-relativistic, charged particle is given by

|

(1275) |

where

denotes a time average. Here, we are effectively treating the oscillating particle as a

short antenna.

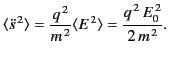

However,

denotes a time average. Here, we are effectively treating the oscillating particle as a

short antenna.

However,

|

(1276) |

Hence, the scattered power per unit solid angle becomes

|

(1277) |

The time-averaged Poynting flux of the incident wave is

|

(1278) |

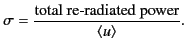

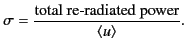

It is convenient to define the scattering cross-section as the equivalent area of the incident wavefront that delivers the same power as that

re-radiated

by the particle: that is,

|

(1279) |

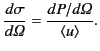

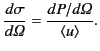

By analogy, the differential scattering cross-section is

defined

|

(1280) |

It follows from Equations (1279) and (1280) that

|

(1281) |

The total scattering cross-section is then

|

(1282) |

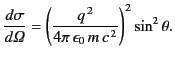

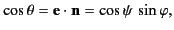

The quantity  , appearing in Equation (1283), is the angle

subtended between the direction

of acceleration of the particle, and the direction of the outgoing radiation

(which is parallel to the unit vector

, appearing in Equation (1283), is the angle

subtended between the direction

of acceleration of the particle, and the direction of the outgoing radiation

(which is parallel to the unit vector  ). In the present case,

the acceleration is due to the electric field, so it is parallel to the

polarization vector

). In the present case,

the acceleration is due to the electric field, so it is parallel to the

polarization vector  . Thus,

. Thus,

.

.

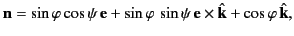

Up to now, we have only considered the scattering of linearly polarized

radiation by a charged particle. Let us now calculate the

angular distribution of scattered radiation for the commonly

occurring case of randomly polarized incident radiation. It is helpful

to set up a right-handed coordinate system based on the three

mutually orthogonal unit vectors  ,

,

,

and

,

and

, where

, where

. In terms of these unit vectors, we can write

. In terms of these unit vectors, we can write

|

(1283) |

where  is the angle subtended between the direction of

the incident radiation and that of

the scattered radiation, and

is the angle subtended between the direction of

the incident radiation and that of

the scattered radiation, and  is an angle that

specifies the orientation of the polarization vector in the plane

perpendicular to

is an angle that

specifies the orientation of the polarization vector in the plane

perpendicular to  (assuming that

(assuming that  is known).

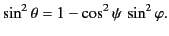

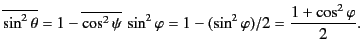

It is easily seen that

is known).

It is easily seen that

|

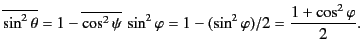

(1284) |

so

|

(1285) |

Averaging this result over all possible polarizations of the

incident wave (i.e., over all possible values of

the polarization angle  ), we obtain

), we obtain

|

(1286) |

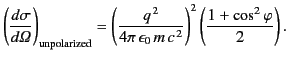

Thus, the differential scattering cross-section for unpolarized incident

radiation [obtained by substituting

for

for

in Eq. (1283)] is given by

in Eq. (1283)] is given by

|

(1287) |

It is clear that the differential scattering cross-section is

independent of the frequency of the incident wave, and is also symmetric

with respect to forward and backward scattering. Moreover, the frequency of

the scattered radiation is the same as that of the incident radiation.

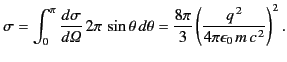

The total scattering cross-section is obtained by integrating over the entire

solid angle of the polar angle  and the azimuthal

angle

and the azimuthal

angle  . Not surprisingly, the result

is exactly the same as Equation (1284).

. Not surprisingly, the result

is exactly the same as Equation (1284).

The classical scattering cross-section (1289) is modified by quantum

effects when the energy of the incident photons,

, becomes

comparable with the rest mass of the scattering particle,

, becomes

comparable with the rest mass of the scattering particle,

. The

scattering of a photon by a charged particle is called Compton

scattering, and the quantum mechanical version of the Compton scattering

cross-section is known as the Klein-Nishina cross-section. As the photon

energy increases, and eventually becomes comparable with the rest mass energy

of the particle, the Klein-Nishina formula predicts that forward scattering

of photons becomes increasingly favored with respect to backward scattering.

The Klein-Nishina cross-section does, in general, depend on the

frequency of the incident photons.

Furthermore, energy and momentum conservation demand a shift in the

frequency of scattered photons with respect to that of the incident photons.

. The

scattering of a photon by a charged particle is called Compton

scattering, and the quantum mechanical version of the Compton scattering

cross-section is known as the Klein-Nishina cross-section. As the photon

energy increases, and eventually becomes comparable with the rest mass energy

of the particle, the Klein-Nishina formula predicts that forward scattering

of photons becomes increasingly favored with respect to backward scattering.

The Klein-Nishina cross-section does, in general, depend on the

frequency of the incident photons.

Furthermore, energy and momentum conservation demand a shift in the

frequency of scattered photons with respect to that of the incident photons.

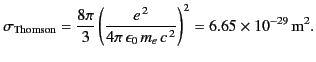

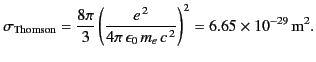

If the charged particle in question is an electron then Equation (1284)

reduces to the well-known Thomson scattering cross-section

|

(1288) |

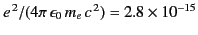

The quantity

m is

called the classical electron radius (it is the radius of spherical

shell of total charge

m is

called the classical electron radius (it is the radius of spherical

shell of total charge  whose electrostatic energy equals the rest mass

energy of the electron). Thus, when scattering radiation, the electron acts rather like

a solid sphere whose radius is of order the classical electron

radius.

whose electrostatic energy equals the rest mass

energy of the electron). Thus, when scattering radiation, the electron acts rather like

a solid sphere whose radius is of order the classical electron

radius.

Next: Rayleigh Scattering

Up: Radiation and Scattering

Previous: Antenna Arrays

Richard Fitzpatrick

2014-06-27

![]() . The electric component of the wave can be

written

. The electric component of the wave can be

written

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() , where

, where

![]() . In terms of these unit vectors, we can write

. In terms of these unit vectors, we can write

![]() , becomes

comparable with the rest mass of the scattering particle,

, becomes

comparable with the rest mass of the scattering particle,

![]() . The

scattering of a photon by a charged particle is called Compton

scattering, and the quantum mechanical version of the Compton scattering

cross-section is known as the Klein-Nishina cross-section. As the photon

energy increases, and eventually becomes comparable with the rest mass energy

of the particle, the Klein-Nishina formula predicts that forward scattering

of photons becomes increasingly favored with respect to backward scattering.

The Klein-Nishina cross-section does, in general, depend on the

frequency of the incident photons.

Furthermore, energy and momentum conservation demand a shift in the

frequency of scattered photons with respect to that of the incident photons.

. The

scattering of a photon by a charged particle is called Compton

scattering, and the quantum mechanical version of the Compton scattering

cross-section is known as the Klein-Nishina cross-section. As the photon

energy increases, and eventually becomes comparable with the rest mass energy

of the particle, the Klein-Nishina formula predicts that forward scattering

of photons becomes increasingly favored with respect to backward scattering.

The Klein-Nishina cross-section does, in general, depend on the

frequency of the incident photons.

Furthermore, energy and momentum conservation demand a shift in the

frequency of scattered photons with respect to that of the incident photons.