Next: Transformation of velocities

Up: Relativity and electromagnetism

Previous: The relativity principle

The Lorentz transformation

Consider two Cartesian frames  and

and

in

the standard configuration, in which

in

the standard configuration, in which  moves in the

moves in the  -direction

of

-direction

of  with uniform velocity

with uniform velocity  , and the corresponding axes of

, and the corresponding axes of

and

and  remain parallel throughout the motion, having

coincided at

remain parallel throughout the motion, having

coincided at  . It is assumed that the same units of distance and

time are adopted in both frames. Suppose that an event

(e.g., the flashing of a light-bulb, or the collision of

two point particles) has coordinates (

. It is assumed that the same units of distance and

time are adopted in both frames. Suppose that an event

(e.g., the flashing of a light-bulb, or the collision of

two point particles) has coordinates ( ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ) relative

to

) relative

to  , and (

, and ( ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ) relative

to

) relative

to  . The ``common sense'' relationship between these two sets of

coordinates is given by the Galilean transformation:

. The ``common sense'' relationship between these two sets of

coordinates is given by the Galilean transformation:

|

|

|

(1324) |

|

|

|

(1325) |

|

|

|

(1326) |

|

|

|

(1327) |

This transformation is tried and tested, and provides a very accurate

description of our everyday experience.

Nevertheless, it must be wrong! Consider a light wave which propagates

along the  -axis in

-axis in  with velocity

with velocity  . According to the Galilean

transformation, the apparent speed of propagation in

. According to the Galilean

transformation, the apparent speed of propagation in  is

is

, which violates the relativity principle. Can we construct a

new transformation which makes the velocity of light invariant between

different inertial frames, in accordance with

the relativity principle, but reduces to the Galilean transformation

at low velocities, in accordance with our everyday experience?

, which violates the relativity principle. Can we construct a

new transformation which makes the velocity of light invariant between

different inertial frames, in accordance with

the relativity principle, but reduces to the Galilean transformation

at low velocities, in accordance with our everyday experience?

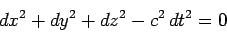

Consider an event  , and a neighbouring event

, and a neighbouring event  , whose coordinates

differ by

, whose coordinates

differ by  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  in

in  , and by

, and by

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  in

in  . Suppose that at the event

. Suppose that at the event  a flash of light is emitted, and that

a flash of light is emitted, and that  is an event in which some

particle in space is illuminated by the flash. In accordance with the

laws of light-propagation, and the invariance of the velocity of

light between different inertial frames, an observer in

is an event in which some

particle in space is illuminated by the flash. In accordance with the

laws of light-propagation, and the invariance of the velocity of

light between different inertial frames, an observer in  will

find that

will

find that

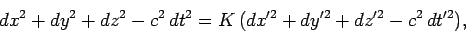

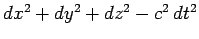

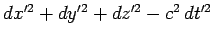

|

(1328) |

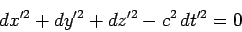

for  , and an observer in

, and an observer in  will find that

will find that

|

(1329) |

for  .

Any event near

.

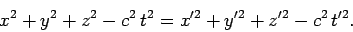

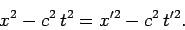

Any event near  whose coordinates satisfy either (1328) or (1329)

is illuminated by the flash from

whose coordinates satisfy either (1328) or (1329)

is illuminated by the flash from  , and, therefore, its coordinates

must satisfy both (1328) and (1329).

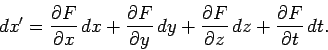

Now, no matter what form the transformation between coordinates in the

two inertial frames takes, the transformation between differentials at

any fixed event

, and, therefore, its coordinates

must satisfy both (1328) and (1329).

Now, no matter what form the transformation between coordinates in the

two inertial frames takes, the transformation between differentials at

any fixed event  is linear and homogeneous. In other words, if

is linear and homogeneous. In other words, if

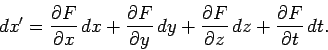

|

(1330) |

where  is a general function, then

is a general function, then

|

(1331) |

It follows that

where

,

,  ,

,  , etc. are functions of

, etc. are functions of  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  .

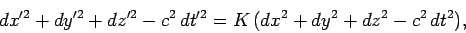

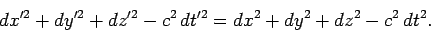

We know that the right-hand side of the above expression vanishes for

all real values of the differentials which satisfy Eq. (1328). It follows

that the right-hand side is a multiple of the quadratic in Eq. (1328):

i.e.,

.

We know that the right-hand side of the above expression vanishes for

all real values of the differentials which satisfy Eq. (1328). It follows

that the right-hand side is a multiple of the quadratic in Eq. (1328):

i.e.,

|

(1333) |

where  is a function of

is a function of  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  .

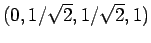

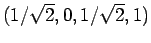

[We can prove this by substituting into Eq. (1332) the following obvious

zeros of the quadratic in Eq. (1328):

.

[We can prove this by substituting into Eq. (1332) the following obvious

zeros of the quadratic in Eq. (1328):

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

: and solving the resulting conditions

on the coefficients.]

Note that

: and solving the resulting conditions

on the coefficients.]

Note that  at

at  is also independent of the choice of standard coordinates

in

is also independent of the choice of standard coordinates

in  and

and  . Since the frames are Euclidian, the values of

. Since the frames are Euclidian, the values of

and

and

relevant to

relevant to  and

and  are independent of the choice of axes. Furthermore, the values of

are independent of the choice of axes. Furthermore, the values of

and

and  are independent of the choice of the origins

of time. Thus, without affecting the value of

are independent of the choice of the origins

of time. Thus, without affecting the value of  at

at  , we can

choose coordinates such that

, we can

choose coordinates such that  in both

in both  and

and  . Since the

orientations of the axes in

. Since the

orientations of the axes in  and

and  are, at present, arbitrary, and

since inertial frames are isotropic, the relation of

are, at present, arbitrary, and

since inertial frames are isotropic, the relation of  and

and

relative to each other, to the event

relative to each other, to the event  , and

to the locus of possible events

, and

to the locus of possible events  , is now completely

symmetric. Thus, we can write

, is now completely

symmetric. Thus, we can write

|

(1334) |

in addition to Eq. (1333). It follows that  .

.  can be

dismissed immediately, since the intervals

can be

dismissed immediately, since the intervals

and

and

must coincide exactly when there is no motion of

must coincide exactly when there is no motion of  relative to

relative to  .

Thus,

.

Thus,

|

(1335) |

Equation (1335) implies that the transformation equations between primed

and unprimed coordinates must be linear. The proof of this statement is

postponed until Sect. 10.7.

The linearity of the transformation allows the coordinate axes in the

two frames to be orientated so as to give the standard configuration

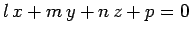

mentioned earlier. Consider a fixed plane in  with the equation

with the equation

. In

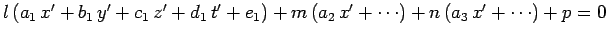

. In  , this becomes (say)

, this becomes (say)

,

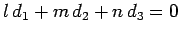

which represents a moving plane unless

,

which represents a moving plane unless

.

That is, unless the normal vector to the plane in

.

That is, unless the normal vector to the plane in  ,

,  ,

is perpendicular to the vector

,

is perpendicular to the vector

. All such planes

intersect in lines which are fixed in both

. All such planes

intersect in lines which are fixed in both  and

and  , and which are

parallel to the vector

, and which are

parallel to the vector

in

in  . These lines must correspond

to the direction of relative motion of the frames. By symmetry, two such

frames which are orthogonal in

. These lines must correspond

to the direction of relative motion of the frames. By symmetry, two such

frames which are orthogonal in  must also be orthogonal in

must also be orthogonal in  . This

allows the choice of two common coordinate planes.

. This

allows the choice of two common coordinate planes.

Under a linear transformation, the finite coordinate differences satisfy the

same transformation equations as the differentials. It follows from

Eq. (1335),

assuming that the events  coincide in both frames,

that for any event with

coordinates

coincide in both frames,

that for any event with

coordinates  in

in  and

and

in

in  , the following relation holds:

, the following relation holds:

|

(1336) |

By hypothesis, the coordinate planes  and

and  coincide

permanently. Thus,

coincide

permanently. Thus,  must imply

must imply  , which suggests that

, which suggests that

|

(1337) |

where  is a constant. We can reverse the directions of the

is a constant. We can reverse the directions of the

- and

- and  -axes in

-axes in  and

and  , which has the effect of interchanging the

roles of these frames. This procedure does not affect Eq. (1337), but

by symmetry we also have

, which has the effect of interchanging the

roles of these frames. This procedure does not affect Eq. (1337), but

by symmetry we also have

|

(1338) |

It is clear that  . The negative sign can again be dismissed,

since

. The negative sign can again be dismissed,

since  when there is no motion between

when there is no motion between  and

and  . The argument

for

. The argument

for  is similar. Thus, we have

is similar. Thus, we have

as in the Galilean transformation.

Equations (1336), (1339) and (1340) yield

|

(1341) |

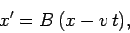

Since,  must imply

must imply  , we can write

, we can write

|

(1342) |

where  is a constant (possibly depending on

is a constant (possibly depending on  ).

It follows from the previous two equations that

).

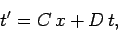

It follows from the previous two equations that

|

(1343) |

where  and

and  are constants (possibly depending on

are constants (possibly depending on  ). Substituting

Eqs. (1342) and (1343) into Eq. (1341), and comparing the coefficients of

). Substituting

Eqs. (1342) and (1343) into Eq. (1341), and comparing the coefficients of

,

,  , and

, and  , we obtain

, we obtain

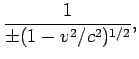

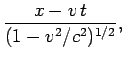

We must choose the positive sign in order to ensure that

as

as

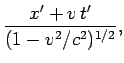

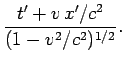

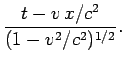

. Thus, collecting our results, the transformation

between coordinates in

. Thus, collecting our results, the transformation

between coordinates in  and

and  is given by

is given by

|

|

|

(1346) |

|

|

|

(1347) |

|

|

|

(1348) |

|

|

|

(1349) |

This is the famous Lorentz transformation. It ensures that

the velocity of light is invariant between different inertial

frames, and also reduces to the more familiar Galilean transform

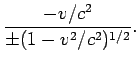

in the limit  . We can solve Eqs. (1346)-(1349)

for

. We can solve Eqs. (1346)-(1349)

for  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  , to obtain the inverse Lorentz

transformation:

, to obtain the inverse Lorentz

transformation:

|

|

|

(1350) |

|

|

|

(1351) |

|

|

|

(1352) |

|

|

|

(1353) |

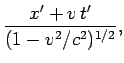

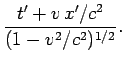

Not surprizingly, the inverse transformation is equivalent to a Lorentz transformation in

which the velocity of the moving frame is  along the

along the  -axis, instead

of

-axis, instead

of  .

.

Next: Transformation of velocities

Up: Relativity and electromagnetism

Previous: The relativity principle

Richard Fitzpatrick

2006-02-02

![]() , and a neighbouring event

, and a neighbouring event ![]() , whose coordinates

differ by

, whose coordinates

differ by ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() in

in ![]() , and by

, and by

![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() in

in ![]() . Suppose that at the event

. Suppose that at the event ![]() a flash of light is emitted, and that

a flash of light is emitted, and that ![]() is an event in which some

particle in space is illuminated by the flash. In accordance with the

laws of light-propagation, and the invariance of the velocity of

light between different inertial frames, an observer in

is an event in which some

particle in space is illuminated by the flash. In accordance with the

laws of light-propagation, and the invariance of the velocity of

light between different inertial frames, an observer in ![]() will

find that

will

find that

![]() with the equation

with the equation

![]() . In

. In ![]() , this becomes (say)

, this becomes (say)

![]() ,

which represents a moving plane unless

,

which represents a moving plane unless

![]() .

That is, unless the normal vector to the plane in

.

That is, unless the normal vector to the plane in ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

is perpendicular to the vector

,

is perpendicular to the vector

![]() . All such planes

intersect in lines which are fixed in both

. All such planes

intersect in lines which are fixed in both ![]() and

and ![]() , and which are

parallel to the vector

, and which are

parallel to the vector

![]() in

in ![]() . These lines must correspond

to the direction of relative motion of the frames. By symmetry, two such

frames which are orthogonal in

. These lines must correspond

to the direction of relative motion of the frames. By symmetry, two such

frames which are orthogonal in ![]() must also be orthogonal in

must also be orthogonal in ![]() . This

allows the choice of two common coordinate planes.

. This

allows the choice of two common coordinate planes.

![]() coincide in both frames,

that for any event with

coordinates

coincide in both frames,

that for any event with

coordinates ![]() in

in ![]() and

and

![]() in

in ![]() , the following relation holds:

, the following relation holds: