Secular evolution of asteroid orbits

Let us now consider the perturbing influence of the planets on the orbit of an asteroid. Because asteroids have much smaller masses than planets, it is reasonable to suppose that the perturbing influence

of the asteroid on the planetary orbits is negligible. Let the asteroid have the standard osculating orbital elements  ,

,

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

, and the alternative elements

, and the alternative elements

,

,

,

,

, and

, and

.

Thus, the mean orbital angular velocity of the asteroid is

.

Thus, the mean orbital angular velocity of the asteroid is

, where

, where  is the solar mass.

Likewise, let the eight planets have the standard osculating orbital elements

is the solar mass.

Likewise, let the eight planets have the standard osculating orbital elements  ,

,

,

,  ,

,

,

,  ,

,

, and the alternative elements

, and the alternative elements

,

,

,

,

, and

, and

, for

, for  .

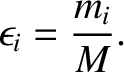

It is helpful to define the following parameters:

.

It is helpful to define the following parameters:

![\begin{displaymath}\alpha_{i} =\left\{

\begin{array}{ccc}

a/a_i&\mbox{\hspace{1cm}}&a_i>a\\ [0.5ex]

a_i/a&&a_i<a

\end{array}\right.,\end{displaymath}](img2641.png) |

(10.85) |

and

![\begin{displaymath}\bar{\alpha}_{i} =\left\{

\begin{array}{ccc}

a/a_i&\mbox{\hspace{1cm}}&a_i>a\\ [0.5ex]

1&&a_i<a

\end{array}\right.,\end{displaymath}](img2642.png) |

(10.86) |

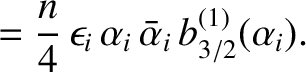

as well as

|

(10.87) |

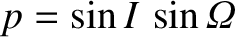

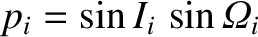

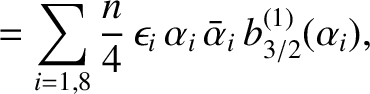

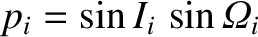

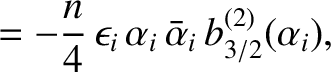

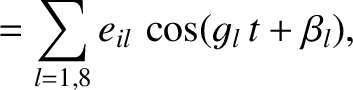

Figure: 10.6

The osculating eccentricity plotted against the sine of the osculating inclination (relative to J2000

equinox and ecliptic) for the orbits of the first 100,000 numbered asteroids at MJD 55400. Raw data from JPL Small-Body Database.

|

|

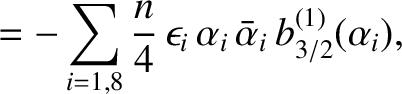

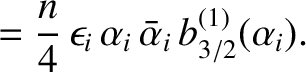

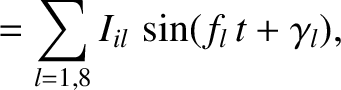

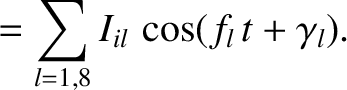

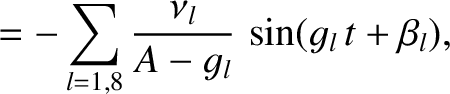

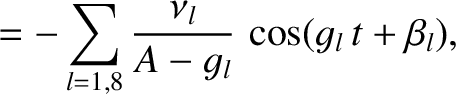

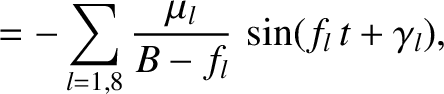

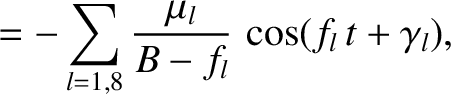

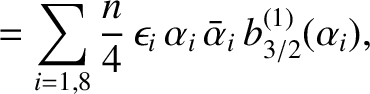

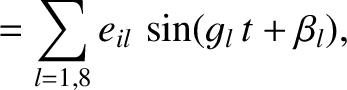

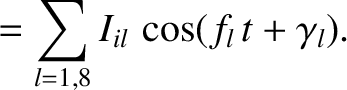

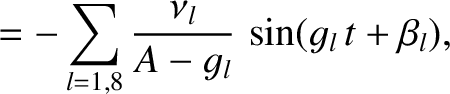

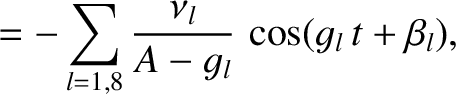

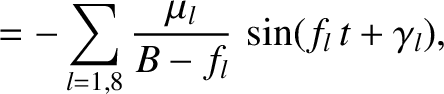

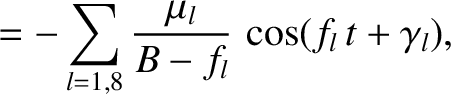

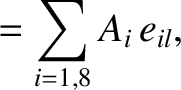

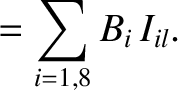

By analogy with the analysis in the previous section, the secular terms in the disturbing function of the asteroid,

generated by the perturbing influence of the planets, cause the asteroid's osculating orbital elements to evolve in time as

where

|

|

(10.92) |

|

|

(10.93) |

|

|

(10.94) |

|

|

(10.95) |

|

|

(10.96) |

|

|

(10.97) |

|

|

(10.98) |

|

|

(10.99) |

|

|

(10.104) |

|

|

(10.105) |

|

|

(10.106) |

|

|

(10.107) |

and

and

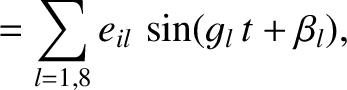

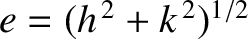

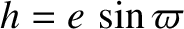

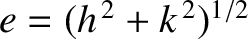

appearing in Equations (10.100)–(10.103)

are the eccentricity and inclination, respectively, that the asteroid orbit would possess were it not for the perturbing

influence of the planets. These parameters are usually called the free, or proper, eccentricity and inclination, respectively.

Roughly speaking, the planetary perturbations cause the osculating eccentricity,

appearing in Equations (10.100)–(10.103)

are the eccentricity and inclination, respectively, that the asteroid orbit would possess were it not for the perturbing

influence of the planets. These parameters are usually called the free, or proper, eccentricity and inclination, respectively.

Roughly speaking, the planetary perturbations cause the osculating eccentricity,

,

and inclination,

,

and inclination,

![$I=\sin^{-1}([p^{\,2}+q^{\,2}]^{1/2})$](img2678.png) , to oscillate about the corresponding free quantities,

, to oscillate about the corresponding free quantities,

and

and

,

respectively.

,

respectively.

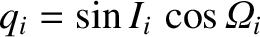

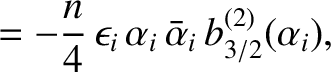

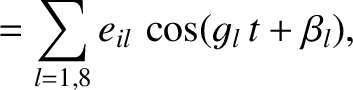

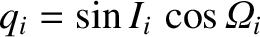

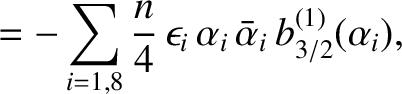

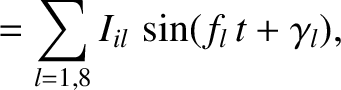

Figure: 10.7

The free eccentricity plotted against the sine of the free inclination (relative to J2000

equinox and ecliptic) for the orbits of the first 100,000 numbered asteroids at MJD 55400. The free orbital elements are determined

from standard Laplace-Lagrange secular evolution theory. The

most prominent Hirayama families are labeled. Raw data from JPL Small-Body Database.

|

|

Figure 10.6 shows the osculating eccentricity plotted against the sine of the osculating inclination

for the orbits of the first 100,000 numbered asteroids (asteroids are numbered in order of their discovery).

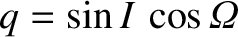

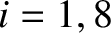

No particular patten is apparent. Figures 10.7 and 10.8 show the free eccentricity plotted against the sine of the

free inclination for the same 100,000 orbits. In Figure 10.7, the free orbital elements

are determined from standard Laplace-Lagrange secular evolution theory, whereas in Figure 10.8 they

are determined from Brouwer and van Woerkom's refinement of this theory. It can be seen that many of the points representing the

asteroid orbits have condensed into clumps. These clumps, which are somewhat clearer in Figure 10.8 than in Figure 10.7, are known as Hirayama families after their discoverer, the Japanese astronomer Kiyotsugu Hirayama (1874-1943). It is thought that the asteroids making

up a given family had a common origin; most likely due to the break up of some much larger body (Bertotti et al. 2003).

As a consequence of this origin, the asteroids originally had similar orbital elements. However, as time

progressed, these elements were jumbled by the perturbing influence of the planets. Thus, only when this

influence is removed does the commonality of the orbits becomes apparent. Hirayama families are named

after their largest member. The most prominent families are the (4) Vesta, (15) Eunomia, (24) Themis, (44) Nysa, (158) Koronis, (221) Eos, and (1272) Gefion families. (The number in brackets is that of the corresponding asteroid.)

Figure: 10.8

The free eccentricity plotted against the sine of the free inclination (relative to J2000

equinox and ecliptic) for the orbits of the first 100,000 numbered asteroids at MJD 55400. The free orbital elements are determined

from Brouwer and van Woerkom's improved secular evolution theory. The

most prominent Hirayama families are labeled. Raw data from JPL Small-Body Database.

|

|

,

,

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,

, and the alternative elements

, and the alternative elements

,

,

,

,

, and

, and

.

Thus, the mean orbital angular velocity of the asteroid is

.

Thus, the mean orbital angular velocity of the asteroid is

, where

, where  is the solar mass.

Likewise, let the eight planets have the standard osculating orbital elements

is the solar mass.

Likewise, let the eight planets have the standard osculating orbital elements  ,

,

,

,  ,

,

,

,  ,

,

, and the alternative elements

, and the alternative elements

,

,

,

,

, and

, and

, for

, for  .

It is helpful to define the following parameters:

.

It is helpful to define the following parameters:

![\begin{displaymath}\alpha_{i} =\left\{

\begin{array}{ccc}

a/a_i&\mbox{\hspace{1cm}}&a_i>a\\ [0.5ex]

a_i/a&&a_i<a

\end{array}\right.,\end{displaymath}](img2641.png)

![\begin{displaymath}\bar{\alpha}_{i} =\left\{

\begin{array}{ccc}

a/a_i&\mbox{\hspace{1cm}}&a_i>a\\ [0.5ex]

1&&a_i<a

\end{array}\right.,\end{displaymath}](img2642.png)

![\includegraphics[height=4in]{Chapter09/fig9_06.eps}](img2644.png)

and

and

appearing in Equations (10.100)–(10.103)

are the eccentricity and inclination, respectively, that the asteroid orbit would possess were it not for the perturbing

influence of the planets. These parameters are usually called the free, or proper, eccentricity and inclination, respectively.

Roughly speaking, the planetary perturbations cause the osculating eccentricity,

appearing in Equations (10.100)–(10.103)

are the eccentricity and inclination, respectively, that the asteroid orbit would possess were it not for the perturbing

influence of the planets. These parameters are usually called the free, or proper, eccentricity and inclination, respectively.

Roughly speaking, the planetary perturbations cause the osculating eccentricity,

,

and inclination,

,

and inclination,

![$I=\sin^{-1}([p^{\,2}+q^{\,2}]^{1/2})$](img2678.png) , to oscillate about the corresponding free quantities,

, to oscillate about the corresponding free quantities,

and

and

,

respectively.

,

respectively.

![\includegraphics[height=4in]{Chapter09/fig9_07.eps}](img2679.png)

![\includegraphics[height=4in]{Chapter09/fig9_08.eps}](img2680.png)