Next: Free precession of Earth Up: Rigid body rotation Previous: Euler's equations

The fixed frame and the body frame share the same origin. Hence, we can transform from one to the other by means of an appropriate rotation of our coordinate axes. In general, if we restrict ourselves to rotations about one of the Cartesian axes, three successive rotations are required to transform the fixed frame into the body frame. There are, in fact, many different ways to combined three successive rotations in order to achieve this goal. In the following, we shall describe the most widely used method, which is due to Euler.

We start in the fixed frame, which has coordinates  ,

,  ,

,  , and

unit vectors

, and

unit vectors  ,

,  ,

,  . Our first rotation

is counterclockwise (if we look down the axis) through an angle

. Our first rotation

is counterclockwise (if we look down the axis) through an angle  about the

about the  -axis. The new frame has coordinates

-axis. The new frame has coordinates  ,

,  ,

,  , and

unit vectors

, and

unit vectors

,

,

,

,

. According

to Section A.6, the transformation of coordinates can be represented as

follows:

. According

to Section A.6, the transformation of coordinates can be represented as

follows:

has the magnitude

has the magnitude

,

and is directed along

,

and is directed along  (i.e., along the axis of rotation).

Hence, we can write

Clearly,

(i.e., along the axis of rotation).

Hence, we can write

Clearly,

is the precession rate about the

is the precession rate about the  -axis,

as seen in the fixed frame.

-axis,

as seen in the fixed frame.

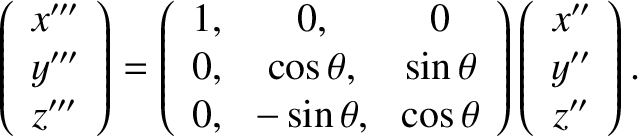

The second rotation is counterclockwise (if we look down the axis) through

an angle  about the

about the  -axis. The new frame has coordinates

-axis. The new frame has coordinates

,

,  ,

,  , and unit vectors

, and unit vectors

,

,

,

,

. By analogy with Equation (8.45), the transformation

of coordinates can be represented as follows:

. By analogy with Equation (8.45), the transformation

of coordinates can be represented as follows:

|

(8.47) |

has the magnitude

has the magnitude

,

and is directed along

,

and is directed along

(i.e., along the axis of rotation).

Hence, we can write

(i.e., along the axis of rotation).

Hence, we can write

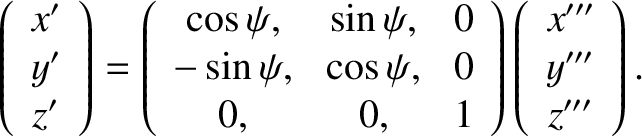

The third rotation is counterclockwise (if we look down the axis) through

an angle  about the

about the  -axis. The new frame is the body frame, which has coordinates

-axis. The new frame is the body frame, which has coordinates

,

,  ,

,  , and unit vectors

, and unit vectors

,

,

,

,

. The transformation of coordinates can be represented as

follows:

. The transformation of coordinates can be represented as

follows:

|

(8.49) |

has the magnitude

has the magnitude

,

and is directed along

,

and is directed along

(i.e., along the axis of rotation).

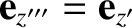

Note that

(i.e., along the axis of rotation).

Note that

, because the third rotation is about

, because the third rotation is about

.

Hence, we can write

Clearly,

.

Hence, we can write

Clearly,

is minus the precession rate about the

is minus the precession rate about the  -axis, as seen in the body frame.

-axis, as seen in the body frame.

The full transformation between the fixed frame and the body frame is rather complicated. However, the following results can easily be verified:

It follows from Equation (8.51) that . In other words,

. In other words,  is the angle of inclination between the

is the angle of inclination between the

- and

- and  -axes.

Finally, because the total angular velocity can be written

Equations (8.46), (8.48), and (8.50)–(8.52)

yield

-axes.

Finally, because the total angular velocity can be written

Equations (8.46), (8.48), and (8.50)–(8.52)

yield

The angles  ,

,  , and

, and  are termed Euler angles. Each has a clear physical interpretation:

are termed Euler angles. Each has a clear physical interpretation:  is the angle of precession

about the

is the angle of precession

about the  -axis in the fixed frame,

-axis in the fixed frame,  is minus the angle of precession about the

is minus the angle of precession about the

-axis in the body frame, and

-axis in the body frame, and  is the angle of inclination

between the

is the angle of inclination

between the  - and

- and  - axes. Moreover, we can

express the components of the angular velocity vector

- axes. Moreover, we can

express the components of the angular velocity vector

in the body frame entirely in terms of the Eulerian angles, and their time derivatives. [See Equations (8.54)–(8.56).]

in the body frame entirely in terms of the Eulerian angles, and their time derivatives. [See Equations (8.54)–(8.56).]

Consider a freely rotating body that is rotationally symmetric about one axis (the  -axis). In the absence of an external torque, the

angular momentum vector

-axis). In the absence of an external torque, the

angular momentum vector  is a constant of the motion. [See Equation (8.3).] Let

is a constant of the motion. [See Equation (8.3).] Let  point along the

point along the  -axis. In the

previous section, we saw that the angular momentum vector subtends a

constant angle

-axis. In the

previous section, we saw that the angular momentum vector subtends a

constant angle  with the axis of symmetry; that is, with the

with the axis of symmetry; that is, with the  -axis. Hence, the time derivative

of the Eulerian angle

-axis. Hence, the time derivative

of the Eulerian angle  is zero. We also saw that the angular momentum

vector, the axis of symmetry, and the angular velocity vector are coplanar.

Consider an instant in time at which all of these vectors lie in the

is zero. We also saw that the angular momentum

vector, the axis of symmetry, and the angular velocity vector are coplanar.

Consider an instant in time at which all of these vectors lie in the  -

- plane. This implies that

plane. This implies that

. According to the

previous section, the angular velocity vector subtends a constant

angle

. According to the

previous section, the angular velocity vector subtends a constant

angle  with the symmetry axis. It follows that

with the symmetry axis. It follows that

and

and

. Equation (8.54) gives

. Equation (8.54) gives

. Hence, Equation (8.55) yields

. Hence, Equation (8.55) yields

|

(8.59) |

|

(8.60) |

is minus the precession rate (of the angular

momentum and angular velocity vectors) in the body frame. On the other hand,

is minus the precession rate (of the angular

momentum and angular velocity vectors) in the body frame. On the other hand,

is the precession rate (of the angular velocity vector

and the symmetry axis) in the

fixed frame. Note that

is the precession rate (of the angular velocity vector

and the symmetry axis) in the

fixed frame. Note that

and

and

are

quite dissimilar. For instance,

are

quite dissimilar. For instance,

is negative for elongated

bodies (

is negative for elongated

bodies (

) whereas

) whereas

is positive definite. It follows that the precession is always in the

same sense as

is positive definite. It follows that the precession is always in the

same sense as  in the fixed frame, whereas the

precession in the body frame is in the opposite sense to

in the fixed frame, whereas the

precession in the body frame is in the opposite sense to  for elongated bodies. We

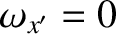

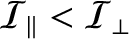

found, in the previous section, that for a flattened body the angular

momentum vector lies between the angular velocity vector and the symmetry

axis. This means that, in the fixed frame, the angular velocity vector

and the symmetry axis lie on opposite sides of the fixed angular

momentum vector, about which they precess. See Figure 8.2. On the other hand, for an elongated body

we found that the angular velocity vector lies between the angular momentum

vector and the symmetry axis. This means that, in the fixed frame, the

angular velocity vector and the symmetry axis lie on the same side of

the fixed angular momentum vector, about which they precess. See Figure 8.2. (Recall that the angular

momentum vector, the angular velocity vector, and the symmetry

axis are coplanar.)

for elongated bodies. We

found, in the previous section, that for a flattened body the angular

momentum vector lies between the angular velocity vector and the symmetry

axis. This means that, in the fixed frame, the angular velocity vector

and the symmetry axis lie on opposite sides of the fixed angular

momentum vector, about which they precess. See Figure 8.2. On the other hand, for an elongated body

we found that the angular velocity vector lies between the angular momentum

vector and the symmetry axis. This means that, in the fixed frame, the

angular velocity vector and the symmetry axis lie on the same side of

the fixed angular momentum vector, about which they precess. See Figure 8.2. (Recall that the angular

momentum vector, the angular velocity vector, and the symmetry

axis are coplanar.)

![\includegraphics[height=2.75in]{Chapter07/fig7_02.eps}](img1649.png)

|