Next: Euler's equations Up: Rigid body rotation Previous: Rotational kinetic energy

, defined in Section 8.3, takes the form of a real symmetric

, defined in Section 8.3, takes the form of a real symmetric  matrix. It therefore follows, from the standard matrix theory discussed in Section A.11,

that the moment of inertia tensor possesses three mutually orthogonal eigenvectors which are associated with three real eigenvalues. Let the

matrix. It therefore follows, from the standard matrix theory discussed in Section A.11,

that the moment of inertia tensor possesses three mutually orthogonal eigenvectors which are associated with three real eigenvalues. Let the  th eigenvector (which can be normalized to

be a unit vector) be denoted

th eigenvector (which can be normalized to

be a unit vector) be denoted

, and the

, and the  th eigenvalue

th eigenvalue  . It then

follows that

for

. It then

follows that

for  .

.

The directions of the three mutually orthogonal unit vectors

define the three so-called principal axes

of rotation of the rigid body under investigation. These axes are special because when the body rotates about

one of them (i.e., when

define the three so-called principal axes

of rotation of the rigid body under investigation. These axes are special because when the body rotates about

one of them (i.e., when

is parallel to one of them) the angular momentum vector

is parallel to one of them) the angular momentum vector  becomes parallel to the angular velocity vector

becomes parallel to the angular velocity vector

.

This can be seen from a comparison of Equation (8.13) and Equation (8.19).

.

This can be seen from a comparison of Equation (8.13) and Equation (8.19).

Suppose that we reorient our Cartesian coordinate

axes so they coincide with the mutually orthogonal principal axes of rotation. In this new reference frame, the eigenvectors of

are the unit vectors,

are the unit vectors,

,

,  , and

, and  , and the eigenvalues

are the moments of inertia about these axes,

, and the eigenvalues

are the moments of inertia about these axes,

,

,

, and

, and

, respectively. These latter quantities are referred to as the

principal moments of inertia.

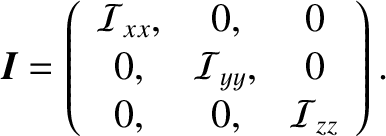

The products of inertia are all zero in the new

reference frame. Hence, in this frame, the moment

of inertia tensor takes the form of a diagonal matrix:

, respectively. These latter quantities are referred to as the

principal moments of inertia.

The products of inertia are all zero in the new

reference frame. Hence, in this frame, the moment

of inertia tensor takes the form of a diagonal matrix:

|

(8.20) |

,

,  , and

, and  are indeed

the eigenvectors of this matrix, with the eigenvalues

are indeed

the eigenvectors of this matrix, with the eigenvalues

,

,

, and

, and

, respectively, and that

, respectively, and that

is indeed parallel to

is indeed parallel to

whenever

whenever

is directed along

is directed along  ,

,  , or

, or  .

.

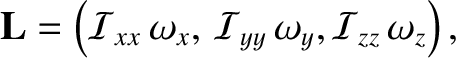

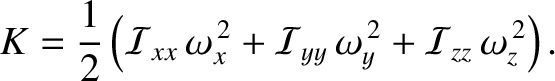

When expressed in our new coordinate system, Equation (8.13) yields

|

(8.21) |

|

(8.22) |

In conclusion, there are many great simplifications to be had by choosing a coordinate system whose axes coincide with the principal axes of rotation of the rigid body under investigation.