Curl

Consider a vector field

, and a loop that lies in one plane.

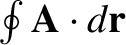

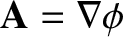

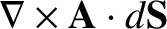

The integral of

, and a loop that lies in one plane.

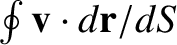

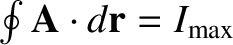

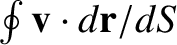

The integral of  around this loop is written

around this loop is written

, where

, where  is a line element of the

loop. If

is a line element of the

loop. If  is a conservative field then

is a conservative field then

and

and

for all loops. In general, for a non-conservative field,

for all loops. In general, for a non-conservative field,

.

.

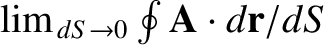

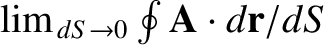

For a small loop, we expect

to be proportional to

the area of the loop. Moreover, for a fixed-area loop, we expect

to be proportional to

the area of the loop. Moreover, for a fixed-area loop, we expect

to depend on the orientation of the loop.

One particular orientation will give the maximum value:

to depend on the orientation of the loop.

One particular orientation will give the maximum value:

. If the loop subtends an angle

. If the loop subtends an angle  with this optimum orientation

then we expect

with this optimum orientation

then we expect

. Let us introduce the vector field

. Let us introduce the vector field

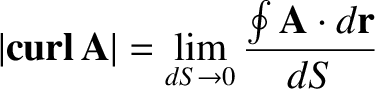

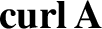

whose magnitude is

whose magnitude is

|

(1.150) |

for the orientation giving

. Here,

. Here,  is the area of the loop.

The direction of

is the area of the loop.

The direction of

is perpendicular to the plane of the loop,

when it is

in the

orientation giving

is perpendicular to the plane of the loop,

when it is

in the

orientation giving

, with the sense given by a right-hand circulation rule.

, with the sense given by a right-hand circulation rule.

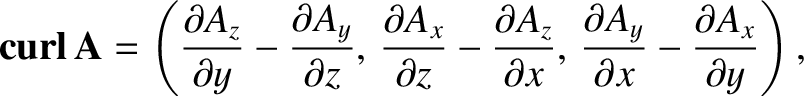

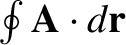

Let us now express

in terms of the components of

in terms of the components of  .

First, we shall

evaluate

.

First, we shall

evaluate

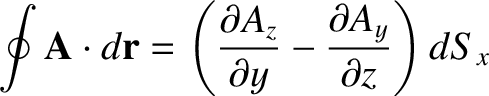

around a small rectangle in the

around a small rectangle in the

-

- plane, as shown in Figure A.25.

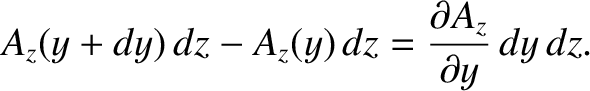

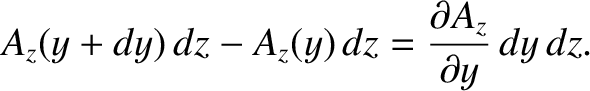

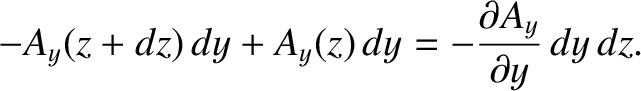

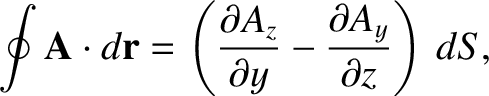

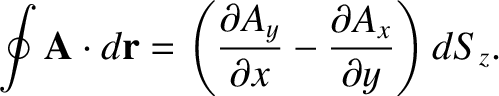

The contribution from sides 1 and 3 is

plane, as shown in Figure A.25.

The contribution from sides 1 and 3 is

|

(1.151) |

The contribution from sides 2 and 4 is

|

(1.152) |

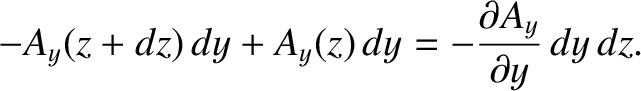

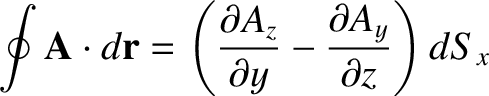

So, the total of all contributions gives

|

(1.153) |

where  is the area of the loop.

is the area of the loop.

Figure: A.25

A vector line integral around a small rectangular loop in the  -

- plane.

plane.

|

|

Consider a non-rectangular (but still small) loop in the  -

- plane.

We can divide it into rectangular

elements, and form

plane.

We can divide it into rectangular

elements, and form

over all the resultant

loops. The interior

contributions cancel, so we are just left with the contribution from the outer loop.

Also, the area of the outer loop is the sum of all the areas of the inner loops.

We conclude that

over all the resultant

loops. The interior

contributions cancel, so we are just left with the contribution from the outer loop.

Also, the area of the outer loop is the sum of all the areas of the inner loops.

We conclude that

|

(1.154) |

is valid for a small loop

of any shape in the

of any shape in the  -

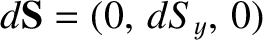

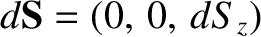

- plane. Likewise, we can show that

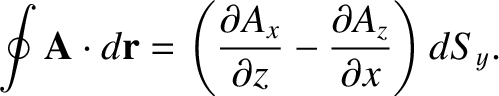

if the loop is in the

plane. Likewise, we can show that

if the loop is in the  -

- plane then

plane then

and

and

|

(1.155) |

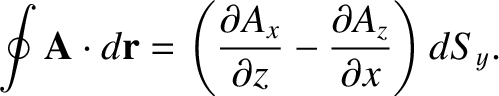

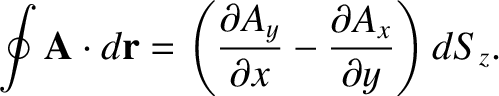

Finally, if the loop is in the  -

- plane then

plane then

and

and

|

(1.156) |

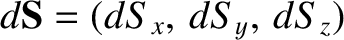

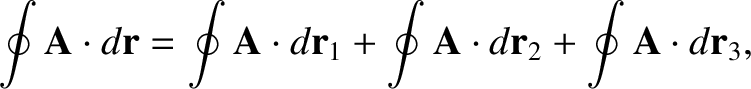

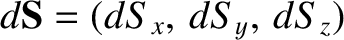

Imagine an arbitrary loop of vector area

. We

can construct this out of three vector areas,

. We

can construct this out of three vector areas,  ,

,  , and

, and  , directed in the

, directed in the  -,

-,  -, and

-, and  -directions, respectively, as

indicated in Figure A.26.

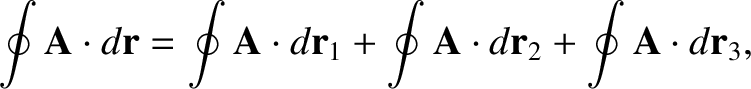

If we form the line integral around all three loops then the interior contributions

cancel, and we are left with the line integral around the original loop. Thus,

-directions, respectively, as

indicated in Figure A.26.

If we form the line integral around all three loops then the interior contributions

cancel, and we are left with the line integral around the original loop. Thus,

|

(1.157) |

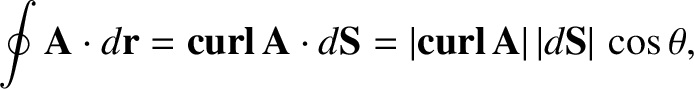

giving

|

(1.158) |

where

|

(1.159) |

and  is the angle subtended between the directions of

is the angle subtended between the directions of

and

and  .

Note that

.

Note that

|

(1.160) |

This demonstrates that

is a good vector field, because it is

the cross product of the

is a good vector field, because it is

the cross product of the  operator (a good vector operator) and

the vector field

operator (a good vector operator) and

the vector field  .

.

Figure A.26:

Decomposition of a vector area into its Cartesian components.

|

|

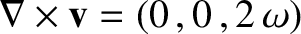

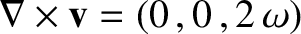

Consider a solid body rotating about the  -axis. The angular velocity is given

by

-axis. The angular velocity is given

by

, so the rotation velocity at

position

, so the rotation velocity at

position  is

is

[See Equation (A.52).]

Let us evaluate

on the axis of

rotation. The

on the axis of

rotation. The  -component is proportional to the

integral

-component is proportional to the

integral

around a loop in the

around a loop in the  -

- plane. This is

plainly zero. Likewise, the

plane. This is

plainly zero. Likewise, the  -component is also zero. The

-component is also zero. The  -component

is

-component

is

around some loop in the

around some loop in the  -

- plane.

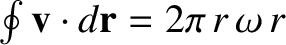

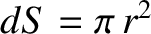

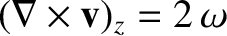

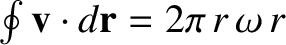

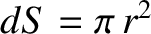

Consider a circular loop. We have

plane.

Consider a circular loop. We have

with

with

.

Here,

.

Here,  is the perpendicular distance from the rotation axis.

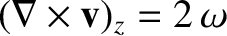

It follows that

is the perpendicular distance from the rotation axis.

It follows that

, which

is independent of

, which

is independent of  . So, on the axis,

. So, on the axis,

.

Off the axis, at position

.

Off the axis, at position  , we can write

The first part has the same curl as the velocity field on the axis, and the

second part has zero curl, because it is constant. Thus,

, we can write

The first part has the same curl as the velocity field on the axis, and the

second part has zero curl, because it is constant. Thus,

everywhere in the body. This allows us to

form a physical picture of

everywhere in the body. This allows us to

form a physical picture of

. If we imagine

. If we imagine

as the

velocity field of some fluid then

as the

velocity field of some fluid then

at any given point is equal

to twice the local angular rotation velocity:

that is, 2

at any given point is equal

to twice the local angular rotation velocity:

that is, 2  .

Hence, a vector field with

.

Hence, a vector field with

everywhere is said to

be irrotational.

everywhere is said to

be irrotational.

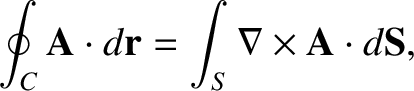

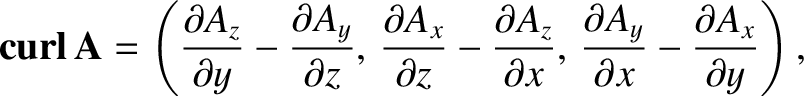

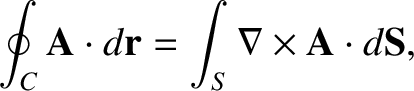

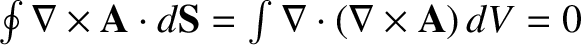

Another important result of vector field theory is the curl theorem:

|

(1.163) |

for some (non-planar) surface  bounded by a rim

bounded by a rim  . This theorem can easily

be proved by splitting the loop up into many small rectangular loops, and forming

the integral around all of the resultant loops. All of the contributions from the

interior loops cancel, leaving just the contribution from the outer rim.

Making use of Equation (A.158) for each of the small loops, we can see that the contribution

from all of the loops is also equal to the integral of

. This theorem can easily

be proved by splitting the loop up into many small rectangular loops, and forming

the integral around all of the resultant loops. All of the contributions from the

interior loops cancel, leaving just the contribution from the outer rim.

Making use of Equation (A.158) for each of the small loops, we can see that the contribution

from all of the loops is also equal to the integral of

across the whole surface. This proves the theorem.

across the whole surface. This proves the theorem.

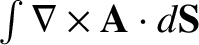

One immediate consequence of the curl theorem is that

is “incompressible.” Consider any two surfaces,

is “incompressible.” Consider any two surfaces,  and

and  , that share the

same rim. (See Figure A.23.) It is clear from the curl theorem that

, that share the

same rim. (See Figure A.23.) It is clear from the curl theorem that

is the same for both surfaces. Thus, it

follows that

is the same for both surfaces. Thus, it

follows that

for any closed surface.

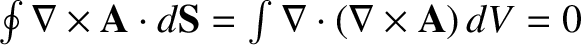

However, we have from the divergence theorem that

for any closed surface.

However, we have from the divergence theorem that

for any volume. Hence,

for any volume. Hence,

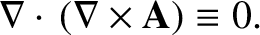

|

(1.164) |

So,

is a solenoidal field.

is a solenoidal field.

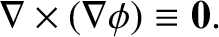

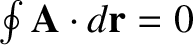

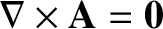

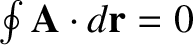

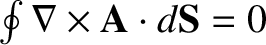

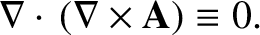

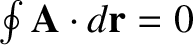

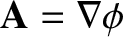

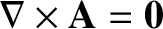

We have seen that for a conservative field

for any loop. This is entirely equivalent to

for any loop. This is entirely equivalent to

.

However, the magnitude of

.

However, the magnitude of

is

is

for some

particular loop. It is clear then that

for some

particular loop. It is clear then that

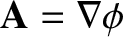

for a conservative field. In other words,

for a conservative field. In other words,

|

(1.165) |

Thus, a conservative field is also an irrotational one.

, and a loop that lies in one plane.

The integral of

, and a loop that lies in one plane.

The integral of  around this loop is written

around this loop is written

, where

, where  is a line element of the

loop. If

is a line element of the

loop. If  is a conservative field then

is a conservative field then

and

and

for all loops. In general, for a non-conservative field,

for all loops. In general, for a non-conservative field,

.

.

to be proportional to

the area of the loop. Moreover, for a fixed-area loop, we expect

to be proportional to

the area of the loop. Moreover, for a fixed-area loop, we expect

to depend on the orientation of the loop.

One particular orientation will give the maximum value:

to depend on the orientation of the loop.

One particular orientation will give the maximum value:

. If the loop subtends an angle

. If the loop subtends an angle  with this optimum orientation

then we expect

with this optimum orientation

then we expect

. Let us introduce the vector field

. Let us introduce the vector field

whose magnitude is

whose magnitude is

. Here,

. Here,  is the area of the loop.

The direction of

is the area of the loop.

The direction of

is perpendicular to the plane of the loop,

when it is

in the

orientation giving

is perpendicular to the plane of the loop,

when it is

in the

orientation giving

, with the sense given by a right-hand circulation rule.

, with the sense given by a right-hand circulation rule.

in terms of the components of

in terms of the components of  .

First, we shall

evaluate

.

First, we shall

evaluate

around a small rectangle in the

around a small rectangle in the

-

- plane, as shown in Figure A.25.

The contribution from sides 1 and 3 is

plane, as shown in Figure A.25.

The contribution from sides 1 and 3 is

is the area of the loop.

is the area of the loop.

-

- plane.

We can divide it into rectangular

elements, and form

plane.

We can divide it into rectangular

elements, and form

over all the resultant

loops. The interior

contributions cancel, so we are just left with the contribution from the outer loop.

Also, the area of the outer loop is the sum of all the areas of the inner loops.

We conclude that

over all the resultant

loops. The interior

contributions cancel, so we are just left with the contribution from the outer loop.

Also, the area of the outer loop is the sum of all the areas of the inner loops.

We conclude that

of any shape in the

of any shape in the  -

- plane. Likewise, we can show that

if the loop is in the

plane. Likewise, we can show that

if the loop is in the  -

- plane then

plane then

and

and

-

- plane then

plane then

and

and

. We

can construct this out of three vector areas,

. We

can construct this out of three vector areas,  ,

,  , and

, and  , directed in the

, directed in the  -,

-,  -, and

-, and  -directions, respectively, as

indicated in Figure A.26.

If we form the line integral around all three loops then the interior contributions

cancel, and we are left with the line integral around the original loop. Thus,

-directions, respectively, as

indicated in Figure A.26.

If we form the line integral around all three loops then the interior contributions

cancel, and we are left with the line integral around the original loop. Thus,

is the angle subtended between the directions of

is the angle subtended between the directions of

and

and  .

Note that

.

Note that

is a good vector field, because it is

the cross product of the

is a good vector field, because it is

the cross product of the  operator (a good vector operator) and

the vector field

operator (a good vector operator) and

the vector field  .

.

-axis. The angular velocity is given

by

-axis. The angular velocity is given

by

, so the rotation velocity at

position

, so the rotation velocity at

position  is

is

on the axis of

rotation. The

on the axis of

rotation. The  -component is proportional to the

integral

-component is proportional to the

integral

around a loop in the

around a loop in the  -

- plane. This is

plainly zero. Likewise, the

plane. This is

plainly zero. Likewise, the  -component is also zero. The

-component is also zero. The  -component

is

-component

is

around some loop in the

around some loop in the  -

- plane.

Consider a circular loop. We have

plane.

Consider a circular loop. We have

with

with

.

Here,

.

Here,  is the perpendicular distance from the rotation axis.

It follows that

is the perpendicular distance from the rotation axis.

It follows that

, which

is independent of

, which

is independent of  . So, on the axis,

. So, on the axis,

.

Off the axis, at position

.

Off the axis, at position  , we can write

, we can write

everywhere in the body. This allows us to

form a physical picture of

everywhere in the body. This allows us to

form a physical picture of

. If we imagine

. If we imagine

as the

velocity field of some fluid then

as the

velocity field of some fluid then

at any given point is equal

to twice the local angular rotation velocity:

that is, 2

at any given point is equal

to twice the local angular rotation velocity:

that is, 2  .

Hence, a vector field with

.

Hence, a vector field with

everywhere is said to

be irrotational.

everywhere is said to

be irrotational.

bounded by a rim

bounded by a rim  . This theorem can easily

be proved by splitting the loop up into many small rectangular loops, and forming

the integral around all of the resultant loops. All of the contributions from the

interior loops cancel, leaving just the contribution from the outer rim.

Making use of Equation (A.158) for each of the small loops, we can see that the contribution

from all of the loops is also equal to the integral of

. This theorem can easily

be proved by splitting the loop up into many small rectangular loops, and forming

the integral around all of the resultant loops. All of the contributions from the

interior loops cancel, leaving just the contribution from the outer rim.

Making use of Equation (A.158) for each of the small loops, we can see that the contribution

from all of the loops is also equal to the integral of

across the whole surface. This proves the theorem.

across the whole surface. This proves the theorem.

is “incompressible.” Consider any two surfaces,

is “incompressible.” Consider any two surfaces,  and

and  , that share the

same rim. (See Figure A.23.) It is clear from the curl theorem that

, that share the

same rim. (See Figure A.23.) It is clear from the curl theorem that

is the same for both surfaces. Thus, it

follows that

is the same for both surfaces. Thus, it

follows that

for any closed surface.

However, we have from the divergence theorem that

for any closed surface.

However, we have from the divergence theorem that

for any volume. Hence,

for any volume. Hence,

is a solenoidal field.

is a solenoidal field.

for any loop. This is entirely equivalent to

for any loop. This is entirely equivalent to

.

However, the magnitude of

.

However, the magnitude of

is

is

for some

particular loop. It is clear then that

for some

particular loop. It is clear then that

for a conservative field. In other words,

for a conservative field. In other words,