Next: Scalar Triple Product Up: Vector Algebra and Vector Previous: Vector Product

whose magnitude

is the angle of the rotation,

whose magnitude

is the angle of the rotation,  , and whose direction is parallel to the axis of

rotation, in the sense determined by a right-hand circulation rule. Unfortunately, this is not a good vector. The problem is that the addition of rotations

is not commutative, whereas vector addition is commuative.

Figure A.11 shows the effect of applying two successive

, and whose direction is parallel to the axis of

rotation, in the sense determined by a right-hand circulation rule. Unfortunately, this is not a good vector. The problem is that the addition of rotations

is not commutative, whereas vector addition is commuative.

Figure A.11 shows the effect of applying two successive  rotations,

one about

rotations,

one about  , and the other about the

, and the other about the  , to a standard six-sided die. In the

left-hand case, the

, to a standard six-sided die. In the

left-hand case, the  -rotation is applied before the

-rotation is applied before the  -rotation, and vice

versa in the right-hand case. It can be seen that the die ends up in two completely

different states. In other words, the

-rotation, and vice

versa in the right-hand case. It can be seen that the die ends up in two completely

different states. In other words, the  -rotation plus the

-rotation plus the

-rotation does not equal

the

-rotation does not equal

the  -rotation plus the

-rotation plus the  -rotation. This non-commuting algebra cannot be

represented by vectors. So, although rotations have a well-defined magnitude and

direction, they are not vector quantities.

-rotation. This non-commuting algebra cannot be

represented by vectors. So, although rotations have a well-defined magnitude and

direction, they are not vector quantities.

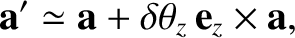

But, this is not quite the end of the story. Suppose that we take a general vector

and rotate it about

and rotate it about  by a small angle

by a small angle

.

This is equivalent to rotating the coordinate axes about the

.

This is equivalent to rotating the coordinate axes about the  by

by

.

According to Equations (A.20)–(A.22), we have

.

According to Equations (A.20)–(A.22), we have

|

(1.48) |

and

and

. The previous equation can easily be generalized to allow

small rotations about

. The previous equation can easily be generalized to allow

small rotations about  and

and  by

by

and

and

,

respectively. We find that

where

,

respectively. We find that

where

|

(1.50) |

, but it only

works for small angle rotations (i.e., sufficiently small that the small-angle approximations of sine and cosine are good). According to the previous equation,

a small

, but it only

works for small angle rotations (i.e., sufficiently small that the small-angle approximations of sine and cosine are good). According to the previous equation,

a small  -rotation plus a small

-rotation plus a small  -rotation is (approximately) equal to

the two rotations applied in the opposite order.

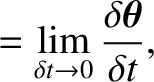

The fact that infinitesimal rotation is a vector implies that angular velocity,

-rotation is (approximately) equal to

the two rotations applied in the opposite order.

The fact that infinitesimal rotation is a vector implies that angular velocity,

|

(1.51) |

is interpreted as

is interpreted as

in Equation (A.49) then it follows that the equation of motion of a vector

that precesses about the origin with some angular velocity

in Equation (A.49) then it follows that the equation of motion of a vector

that precesses about the origin with some angular velocity  is

is