By symmetry, supersonic flow in a concave corner that turns though an angle ![]() is equivalent to one half of the flow

pattern that results when a supersonic fluid is normally incident on a symmetric wedge of nose angle

is equivalent to one half of the flow

pattern that results when a supersonic fluid is normally incident on a symmetric wedge of nose angle ![]() . This

is illustrated in Figure 15.4. It is clear, from the figure, that the presence of the wedge only affects the flow in the

region that lies to the right of the two shock fronts that are attached to the wedge apex,

. This

is illustrated in Figure 15.4. It is clear, from the figure, that the presence of the wedge only affects the flow in the

region that lies to the right of the two shock fronts that are attached to the wedge apex, ![]() . In particular,

the presence of the apex at

. In particular,

the presence of the apex at ![]() only affects the flow in the region that lies to the right of the shock fronts.

only affects the flow in the region that lies to the right of the shock fronts.

The part of Figure 15.2 that we are presently considering (i.e.,

![]() ) is such that a decrease in the

wedge angle,

) is such that a decrease in the

wedge angle, ![]() , corresponds to a decrease in the wave angle,

, corresponds to a decrease in the wave angle, ![]() . When

. When ![]() decreases to zero (causing the wedge to disappear),

decreases to zero (causing the wedge to disappear), ![]() decreases to the

limiting value

decreases to the

limiting value ![]() . Moreover, the shock strength (which parameterizes the jump in quantities across the shock front) becomes

zero. (See Section 15.4.) In fact, there is no disturbance in the flow in the limit

. Moreover, the shock strength (which parameterizes the jump in quantities across the shock front) becomes

zero. (See Section 15.4.) In fact, there is no disturbance in the flow in the limit

![]() . Thus, in Figure 15.4, there is no longer anything

unique about the point

. Thus, in Figure 15.4, there is no longer anything

unique about the point ![]() ; indeed, this point might correspond to any

point in the flow. The angle

; indeed, this point might correspond to any

point in the flow. The angle ![]() is simply a characteristic angle associated with the local Mach number of the flow, according to

the relation (15.6). As we have already mentioned,

is simply a characteristic angle associated with the local Mach number of the flow, according to

the relation (15.6). As we have already mentioned, ![]() is known as the Mach angle. Note that

is known as the Mach angle. Note that

![]() for

for

![]() .

.

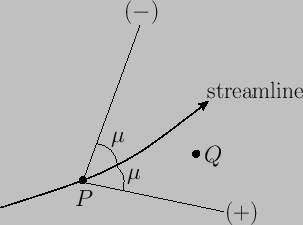

The lines of inclination ![]() (with respect to the upstream directed streamline) that may be drawn at any point in the flow are known as Mach lines. At a general point,

(with respect to the upstream directed streamline) that may be drawn at any point in the flow are known as Mach lines. At a general point, ![]() , there are always two lines that intersect the local streamline at the angle

, there are always two lines that intersect the local streamline at the angle ![]() . (In three-dimensional flow, the Mach lines

define a conical surface with apex

. (In three-dimensional flow, the Mach lines

define a conical surface with apex ![]() , known as a Mach cone.) Thus, a two-dimensional supersonic flow pattern is associated with

two families of Mach lines. These are conventionally distinguished by the labels

, known as a Mach cone.) Thus, a two-dimensional supersonic flow pattern is associated with

two families of Mach lines. These are conventionally distinguished by the labels ![]() and

and ![]() . Those lying in the

. Those lying in the ![]() set

run to the right of the (upstream directed) streamline, whereas those in the

set

run to the right of the (upstream directed) streamline, whereas those in the ![]() set run to the left. (See Figure 15.5.) Mach lines are also sometimes called characteristics.

It is clear, from our previous discussion, that the flow conditions at point

set run to the left. (See Figure 15.5.) Mach lines are also sometimes called characteristics.

It is clear, from our previous discussion, that the flow conditions at point ![]() can only affect those at some other point

can only affect those at some other point ![]() if the latter point

lies between the

if the latter point

lies between the ![]() and

and ![]() Mach lines passing through point

Mach lines passing through point ![]() .

(See Figure 15.5, as well as Exercise ii.) Hence,

we deduce that, unlike subsonic flow, there is no upstream influence in supersonic flow.

.

(See Figure 15.5, as well as Exercise ii.) Hence,

we deduce that, unlike subsonic flow, there is no upstream influence in supersonic flow.

Oblique shocks can also be distinguished by the labels ![]() and

and ![]() , according to which set of characteristics they

asymptote to in the limit of zero shock strength.

, according to which set of characteristics they

asymptote to in the limit of zero shock strength.

|